Published on Hibr in March 2011.

In Lebanon, a sectarian system built to represent all of this country’s various faiths means that feeling invisible is a rare thing. Chances are that there is at least one zaim claiming to speak for your interests at any given time. And yet, for Lebanon’s Baha’i community, invisibility is a fact of life; they remain one of the few religious groups of Lebanese citizens that remain legally unrecognized by the Constitution as one of the country’s 18 official sects.

Despite the lack of governmental persecution against the Baha’i Faith in Lebanon, a history of persecution throughout the region coupled with a lack of recognition might give Lebanon’s Baha’is a reason to stay alert. Nevertheless, this seemingly invisible 19th sect lacks political parties, militias, or any sort of political movement for recognition.

Flight from Persia

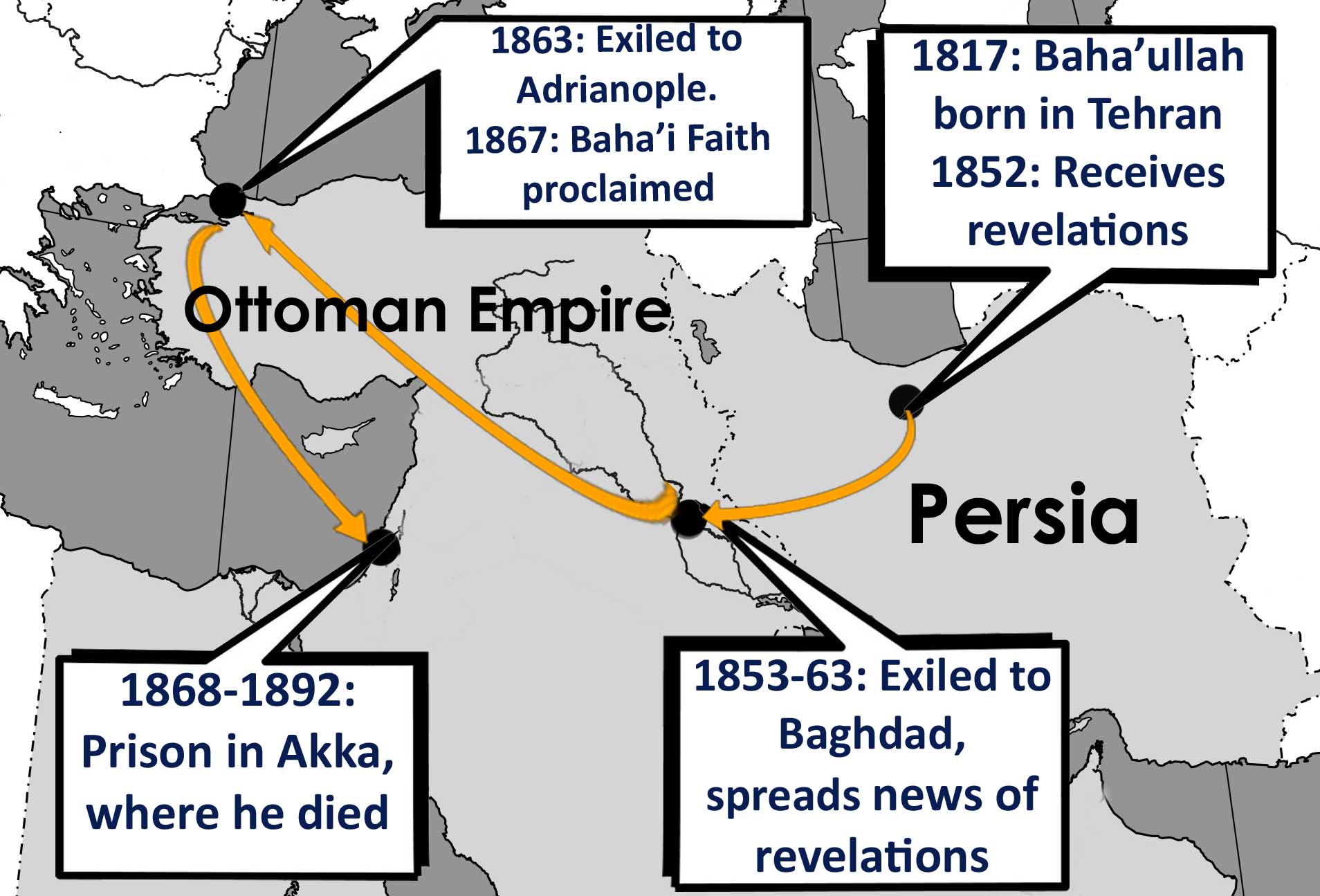

The Baha’i Faith originated in 19th century Iran (then Persia) when a young man named Mirza Hussein Ali Nuri began to experience divine revelations informing him that he was next in the line of Abrahamic prophets. Nuri, who renamed himself Baha’u’llah, went on to develop a faith that stresses the oneness of god and condemns extremism of any sort, calling for gender equality and an end to prejudice. The Baha’i Faith, as the religion came to be known, believes that Baha’u’llah does not contradict previous prophets but continues a revelation of divine will that is ongoing in every age.

Members of the Baha’i Faith, beset by persecution in Persia and the Ottoman Empire, began filtering into what is today called Lebanon, Palestine, and Egypt in the 1870s. In the first half of the 20th century, the American University of Beirut played a pivotal role in the education of the Iranian Baha’i leadership due to its tolerance of diversity and proximity to their holiest shrine in Haifa.

A Lebanese community invisible at home and threatened abroad

Since then, scores of Iranian Baha’is have settled here and scores of Lebanese have converted into the Faith. Although estimates are difficult to come by, it is thought that today hundreds of Lebanese citizens belong to the Baha’i Faith out of a population of some seven million worldwide.

While there are no major centers in Lebanon for the Baha’is, a religious council exists in Mashghara, a town near Jezzine in South Lebanon, while there are two Baha’i cemeteries, located in Khaldeh and Mashghara. Lebanese Baha’is who descend from non-Baha’i families cannot generally identify as Baha’i on official documents, however, and instead retain their pre-conversion sect on their identity papers. This sect varies but is often Shi’a, as Baha’ism itself began as a reformist movement with Shi’ism. Some Baha’is, however, have managed to get “Baha’i” written on their papers.

Although the Lebanese government feigns indifference to its Baha’i citizens, elsewhere in the region Baha’is are often considered heretics, a view spread by the mainstream Sunni and Shi’a religious establishments of Al Azhar and Qom respectively. These institutions’ influence extends into their respective communities in Lebanon, and so it is not hard to imagine that antagonism towards Baha’is might be widespread here as well.

“The future of the community moves with the future of Lebanese society”

So what is it like to be a part of a system built on the idea of sectarian distribution when your sect is unrecognized, your faith is ill-understood, and the few people in the region interested in you think you are a bunch of apostates?

Interestingly, few Bahai’s in Lebanon complain of harassment or persecution from their neighbors or authorities. One member of the Faith, a Beirut resident who preferred to remain anonymous, asserted, “There is no serious discrimination or antagonistic attitudes, possibly because of the diversity of Lebanon.” He added, “The Baha’i community in Lebanon is not an isolated entity in a larger body; the future of the community moves with the future of Lebanese society, in good or bad.”

Historically home to many faiths, it seems that despite repeated bouts of civil conflict most Lebanese are still used to living in coexistence with diverse neighbors, a fact the Baha’i community can testify to. Given this, why is political recognition not forthcoming?

The principal explanation can be found in the religious beliefs of the Baha’i Faith. The Faith eschews political activity of any sort, instead encouraging believers to be dutiful and faithful citizens of the country in which they live and to engage in action for social welfare and reform. Further, it forbids active political involvement, such as the creation of political parties or running for office, although believers are allowed to vote as long as this does not promote partisanship or bring persecution upon the Baha’i community. Baha’is in Lebanon are therefore prevented from entering – or even actively petitioning to join – Lebanon’s confessional system. If a Baha’i did run for any political office, he or she would be subsequently “expelled” from the Baha’i community, explained a believer who wished to remain anonymous.

At first glance, the Baha’i Faith’s lack of considerable visibility in Lebanon might suggest fragility or a threatened status. Conversely, however, in this age of Arab democratic revolution and weekly anti-sectarian marches, their invisibility and lack of involvement in Lebanon’s divisive sectarian politics is a sign of their health and just how far ahead of the curb this small religious community really is.