Originally published by Ajam Media Collective on December 27, 2011.

Tehran is a city defined by a distinctly “Islamic modernity.” Although some have said it is not an “interesting” city (as Asef Bayat does in his brilliant article on the city’s urban development originally published in the New Left Review) and others have called it downright ugly, it has always held a special appeal for me. From a young age, it served as the summer counterpart to my school-year city, Los Angeles, a fascinating tangle of futuristic skyscrapers, winding highways, mosques lit up like discotheques, and back alleys filled with squarish, old yellow-brick houses. It made LA- “72 suburbs in search of a city,”- feel decidedly staid in comparison every August when I returned.

And yet, every once in a while as I wandered Tehran’s boulevards and side streets, it appeared to me as if the immigration to Los Angeles (of people, of thoughts) had not been one-way; in fact, the city’s wildly varying urban structure shared much of the features of urban Southern California that I was used to.

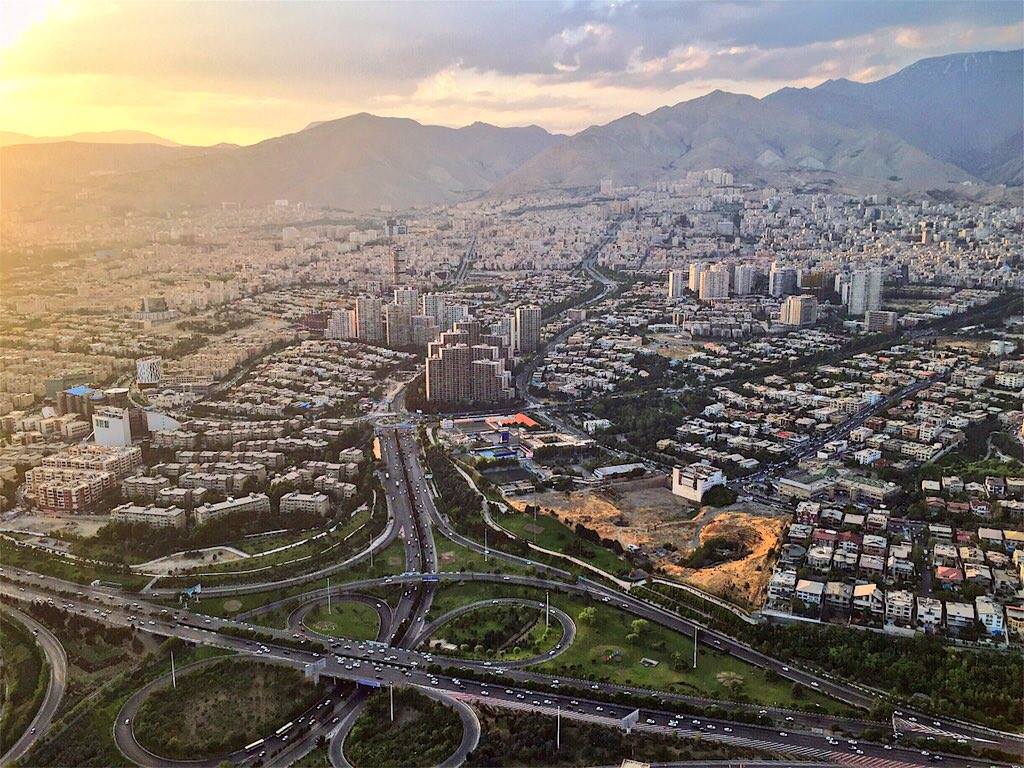

Some months ago I had the opportunity to visit the top of Milad Tower in central Tehran, one of the few places in this city (besides the northern mountains) from which one can get a grip on the place, and a fascinating bird’s eye view on its urban structure.

Planned for the most part according to design principles as established by American urban planners in a master plan set out in the 1960’s, Tehran’s urban fabric is chopped up by a freeway system that outdoes Los Angeles both in complexity and traffic congestion.

Between these freeways lie communities sitting next to eachother but at the same completely distinct from one another- megaprojects tower over “villas” designed to imitate 1970’s Southern California suburbs while both are swallowed by the low rise, blocky, but pedestrian-friendly sprawl that characterizes Tehran’s unplanned quarters.

In these pictures, Shahrake Qods (“Jerusalem Town”) is visible, dating to the 1960’s, and consisting of a mix of bungalows and towers.

At the center of this lies Milad Tower, which at 435 meters high is the 6th tallest tower in the world. Built in a gaping hole in the urban fabric until recently left empty save for a few freeways, it is part of a sort of urban infill project and is accompanied by a hospital, a convention center, and touristic facilities.

The best part, though, is getting to stand above it all and take this megacity in from the middle!

Since the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the master plan has been kept as a basic skeleton of urban design. However, many of the guidelines regarding individual projects has been disregarded, for better or worse. Add to this the chaos of unplanned building from the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq War, when Saddam Hussein invaded the Southwest of the country and displaced millions (many of whom came to Tehran, even though he launched missiles on the capital as well), and the hurdles facing Tehran urban planners become obvious.

For the moment, however, just sit back and look at the freeway rivers flowing between the various megaprojects, placed almost at random in this city of over 13 million people.

Downtown Tehran, an area dating to the 1800’s but mostly built in around the turn of the 20th century and planned alongside a bazaar about two centuries old, was left untouched by the orgy of freeway construction. Most highrises, meanwhile, are in commercial and residential quarters of the far north of Tehran, leaving downtown a mostly low-rise, historic area.

Gisha, the neighborhood just south of the Milad Tower, is an example of the dense development that extends in the unplanned spaces between the megaprojects. The grid, interestingly, lies over a very steep, hilly area (hard to see from this height), but does not budge an inch.

Today, many subdivisions consist of tower blocks centered around parks and a mosque. This inner-city development, however, is low-rise but denser. However, because of the many gaps in Tehran’s urban fabric and a very pro-active department of urban planning, Tehran is a famously green city, and parks and pocket parks can be found every few blocks in most neighborhoods.

Despite the mess, the shoddy constructions, and the overwhelming disorder of the place, there is something delightfully charming about it all. The varying and contradicting mandates of urban planners, clerics, municipal officials, and others have all coalesced into an unpredicted vision of an urban future with little precedent in our past or any equal abroad. Indeed, for all its newness it lacks the staid and authoritarian uniformity of planned new cities like Delhi, Levittown or Brasilia.

Instead of the urban planner’s singular vision, contested by actual residents, that these cities offer, Tehran’s map offers hundreds of visions of Iran and a hundred definitions of modernity, all simultaneously at odds with the other and constantly contested, evaluated, and re-articulated by 10 million inhabitants. At the very least, it sure is one amazing place to spend your summers…

Originally published by the author at Citynoise.