Originally published by Ajam Media Collective on April 12, 2012.

Over the last few decades, Iranian cinema has burst onto the global stage, earning worldwide acclaim and, most recently, a Golden Globe and an Oscar. No major film festival is complete without at least one Iranian film these days, and it’s no longer hyperbole to suggest that the Iranian film vies against the Persian carpet for the position of the country’s most celebrated cultural and artistic export.

It comes as quite a surprise to many abroad, however, when they learn that while Iran has one of the most productive film industries in the world, the vast majority of the nation’s roughly 150 new releases each year are a mixture of cheap slapstick and drawn out melodrama. Indeed, while most Iranian films for export are long, art-house flicks exploring intricate social themes, the films that make for smash hits in the domestic market are not all that different from the kinds of movies Hollywood churns out, albeit with significantly less sexual content. And while the majority of these films deal with the kinds of apolitical fare familiar to Western audiences, every once in awhile a few overtly political films enjoy great success and offer a fascinating look at the politics of the Iranian Box Office.

Over the Persian New Year holidays (spanning the end of March), two new releases sparked a bit of controversy for quite different reasons. The first film, entitled Gasht-e Ershad (Morality Police), is a slightly wacky comedy following a group of young men who pretend to be morality police as part of a scheme to earn some extra cash.

The actual morality police are a parastate band of volunteers who wander public spaces in Iranian cities harassing youth they judge as being up to no good, and a film suggesting alterior motives for their hard-assery appeals to the youth who form a big chunk of Iran’s movie-going population. The trailer, in Persian, is below:

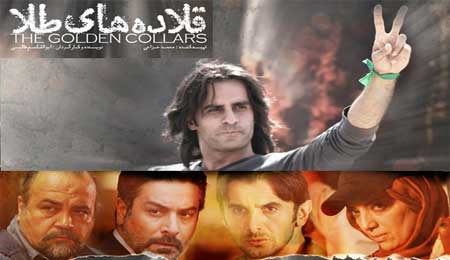

The second movie, Ghaladehaye Tala (Golden Collars), tells the story of the lead up to the 2009 Presidential Elections and the Green Movement that followed from the perspective of its critics.

This fictional film focuses on allegations of foreign involvement in the protests, portraying a network of spies, assassins, and violent rioters who square off against the Iranian police (who engage in their own share of violence).

Both films have engendered a great deal of controversy, albeit from wildly different sectors of the population. Golden Collars has generated a facebook group calling for a Boycott with over 6,000 likes so far, with critics charging that it is based on unsubstantiated rumors of foreign involvement in what was essentially a repressed domestic civil rights movement. They charge the actors with being the ones on “golden leashes” (a phrase referencing mercenaries), not the protesters, and are outraged because with scores dead and hundreds still in jail because of their involvement in the protests, the film represents to them a grave insult.

The film no doubt reflects the views of many in the government regarding the protests (though a few surveys taken of Iranian public opinion over the last few years suggest that more Iranians than expected might agree with their government). This says nothing of the dubitable veracity of the film’s alleged plot points, of course, but it might portend financial success for the film.

Morality Police offers a similarly complicated tale. The real-life morality police is a major public institution, a force comprising thousands of men and women who take into their own hands the enforcement of a particular vision of Islamic morality and dress code in the public sphere. The fact that a film mocking them was permitted by the Iranian censors reflects the sometime surprising standards of acceptable dissent and critique in the Islamic Republic. The film is, in that sense, by no means unprecedented, as many Iranian films critique various aspects of the ruling class.

Marmulak, is a classic example of a comedy targeting the clerics. This 2004 film follows a criminal who escapes from prison in clerical garb and through a series of mishaps is mistakenly installed as the new cleric of the small border town he is attempts to flee the country from.

The film challenges notions of religious orthodoxy and stresses the possibility of “different paths to God” through its exploration of crime, forgiveness, and repentance. Besides the humorous jabs at the clerical institution (though clerics are more generally presented as mixed bag), the disjuncture in the film between individual repentance and state-enforced punishment points to the flaws inherent in any institutionalized system of justice.

After public protests by supporters of the morality police, however, and a cleric’s condemnation of the film as “obscene,” the film Morality Police was banned soon after its release. It is notable here that it was not the government censors that had a problem with the film but influential members of the public, highlighting some of the paradoxes of tolerable free speech in the country.

Iranian cinema emerges from across a diverse, multi-layered system of production that includes both government funding and independent investment. Although it has become commonplace outside of Iran to simplify the domestic political situation to one of unending oppression, the diversity of themes in Iranian cinema tackled reveals a vibrant public sphere in which controversial topics are readily discussed.

Here, the lines of acceptable dissent are constantly being reformulated and redefined in an intricate push-and-pull between cultural producers, government censors, and a vocally opinionated public. And although Iranian cinema often courts social and political controversy, in Iran, like everywhere else, the people ultimately just want to be entertained.