Originally published by Ma’an News Agency on February 21, 2014.

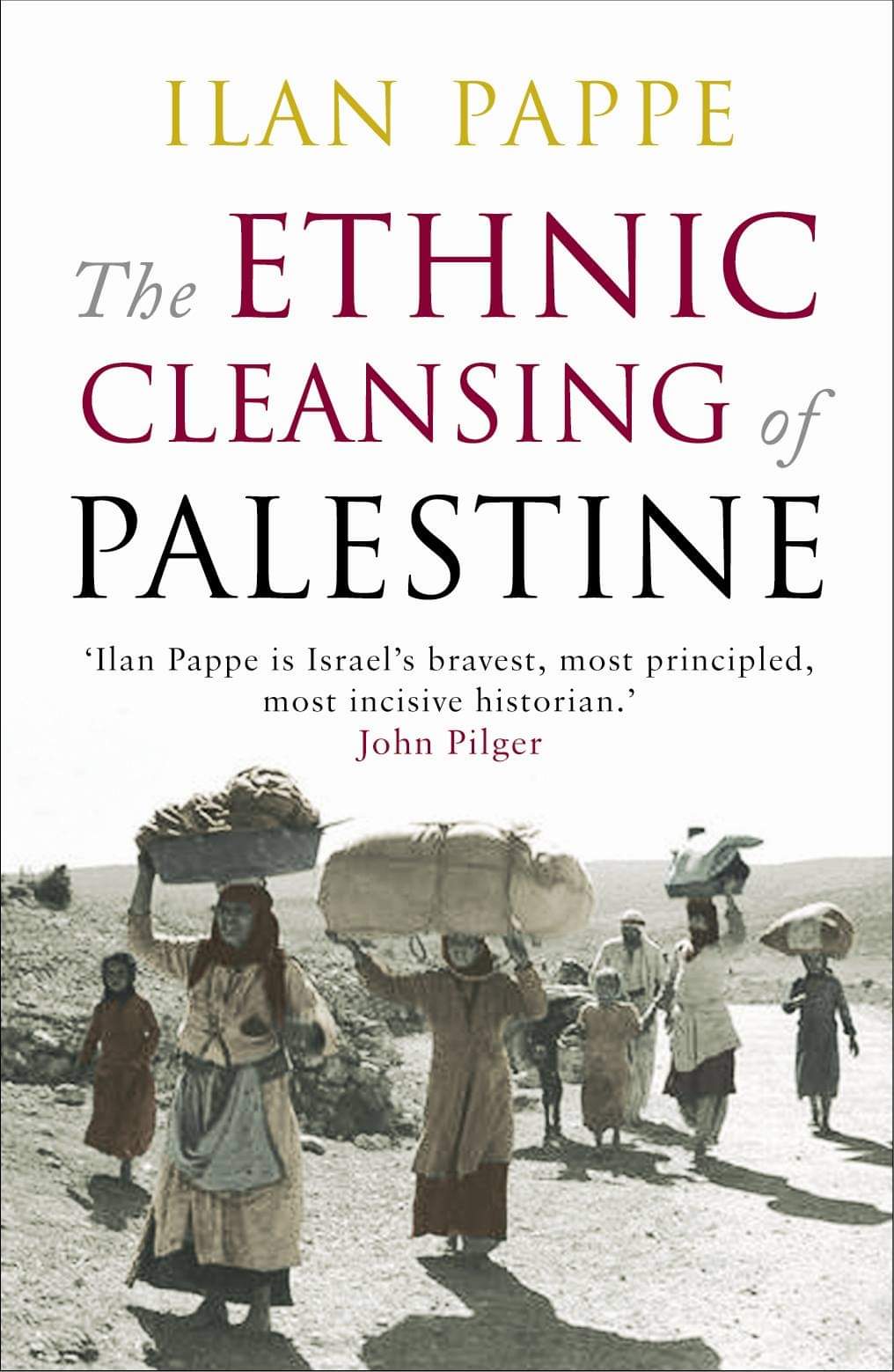

Ilan Pappe is an Israeli historian and political activist. Much of Pappe’s academic work has focused on the 1948 expulsion of 700,000-800,000 Palestinians from their homes in what became the State of Israel. He recently announced that he would begin translating his book “The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine,” through crowd-sourcing on Facebook. The move came after years in which he was unable to find a translator and publisher inside Israel.

Ma’an recently conducted an interview with him to discuss his decision to crowd-source book translation, the state of academic freedom in Israel, and the American Studies Association’s recent decision to endorse the boycott of Israeli academic institutions.

What was the process that led to the decision to translate the book via Facebook? You mentioned online that so far you had been unable to find a publisher in Israel. How has that process of trying to publish the book in Hebrew been? What have been the major obstacles? Were they related to potential financial backlash against the publishers, or were more ideological factors at play in your opinion?

The book was already finished in 2006, and I think I was already then aware that the chances of publishing it in Hebrew would be slim, but I have tried several publishers and the answer was candid and ideological. They would not publish such a book. On top of it the major bookshop chain in Israel, Steimatzky, has boycotted my books even before that. So it was either hoping that people would read it in English, or looking for alternative ways.

What is the state of the publishing industry with regards to opinions critical of Zionism, in your opinion? How is it similar or different to the climates in academic institutions? Can you tell us a little bit about the obstacles you faced while working in an Israeli university?

In academia and the publishing world, and other cultural media like this, there are certain invisible red lines that you know there are there only when you cross them. In principle, I would say you are not allowed to base your criticism on Zionism on the basis of your professional credentials and know-how. Namely, you can teach, study or publish critique of Zionism based on your convictions or activism; so you be a chemist who criticizes the government’s policies or even the state’s ideology. Not that there are many people like that either, but this has to do more with self censorship than anything else.

But critique of Zionism as a pastime or political activity (provided you are a Jewish citizen of course) is somehow tolerated. But if you claim that Zionism as an ideology is morally corrupt and that its policies are war crimes on the basis of your professional credentials, for instance as a historian trained in the history of Israel and Palestine, you have crossed a red line. Because obviously this what you will teach your students or instruct the future teachers of the state.

Similarly, if you accuse your own reference group as being part of the oppression you have crossed a red line, and of course it is worse if you believe it should be boycotted for its complacency. This is why even the bravest journalists we have would not attack their own place-work for their role in maintaining the oppression and this is why so few academics in Israel were willing even to ask the question of how involved are their institutions in the criminal reality on the ground.

Finally, if you critique not the state policies, but its very nature and doubt publicly its moral justification and basis your out of the “legitimate” boundaries and if you dare drawing comparisons with the darkest moments in Jewish and European history to the current realities you will not be tolerated. Well I have crossed all these red lines and the result was that I could not work any more in an Israeli academic institution, which instead of being bastions of freedom of expression are bastions of censoring expression.

In my case, what it meant was being excluded from the right to participate in academic conferences, let alone organize them, harassment on allegedly administrative issues, picking on my post graduate students, inciting the student community against me (by staging demonstrations in front of my classroom) and finally calling publicly for my resignation and putting on trial in front of a disciplinary court for my lack of patriotism and collegiality. What was amazing that the harassment continued to Britain where I began working in 2007. For years the Israeli ambassador in London exerted pressure, that was of course fended off, on my university to fire me! Even in the worst days of Apartheid, the South African ambassador would not call upon British universities to fire anti-apartheid staff.

On a related note, how do you see obstacles you have faced in relationship to the recent American Studies Association decision to boycott Israeli academic institutions? Do you see this a positive step that might serve to embolden dissident voices in Israeli institutions?

I think it is a highly inspiring example of academic bravery (quite often an oxymoron) that sends the right message to the Israeli academics that the people they value most and the institutions they emulate almost religiously can not understand, nor accept, their complacency in maintaining the oppression and their indifference to atrocities committed few miles from their places of learning which are done in their name.

The vote makes the interesting move of linking the academic freedom of US-based academics (with regards to speaking critically about Israeli policies) to the academic freedom of Palestinian academics.

How do you understand “academic freedom” in relation to your own experience? Do you see the vote as harming the academic freedom of Israeli academics? What was your experience of academic freedom in Israel as a dissident Israeli academic?

First of all, the link is obvious but indeed had to be articulated for the American public. I really think that if American academics would have a full picture of life as academics and students under occupation in the West Bank and siege in the Gaza Strip means they would even come in greater number to support the cause of peace and justice in Palestine. This kind of act in fact enhances academic freedom. It opens up the boundaries of academic conversation which were demarcated ideologically by the Israeli academia. Freedom of academic expression in Israel is a bit like the idea of a Israel being a Jewish democracy.

You take a universal concept — everyone has the right to their opinion and everyone has the right to be part of a democracy — only with one condition: that the universality does not include critique on Zionism and that the democracy would always ensure Jewish majority whatever the demographic and geographical realities are. The action of Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS), including the latest support given by one American academic society after the other, does not allow this travesty to continue. Either you are condoning academic freedom and democracy for all, or you are censoring the debate and imposing an Apartheid regime (which include not allowing any academic freedom for the occupied Palestinians). There is no middle road. So the latest actions are the best lesson on academic freedom Israelis have ever received since the state was created.

Finally, how is the work of translating to Hebrew via Facebook going so far? And how can readers support your work?

I have already published three chapters, with a forth on the way, and reactions have been great. It also enabled me to engage in live discussion about the material and were possible post documents and sources. I need as many Israelis to read about it and my friend of FB are doing their best in spreading the word, which was a great gift for me for 2014.