Originally published by Ma’an News Agency on March 27, 2014.

“The Ceremonial Vniform” opened to the public at Birzeit University Museum on March 20.

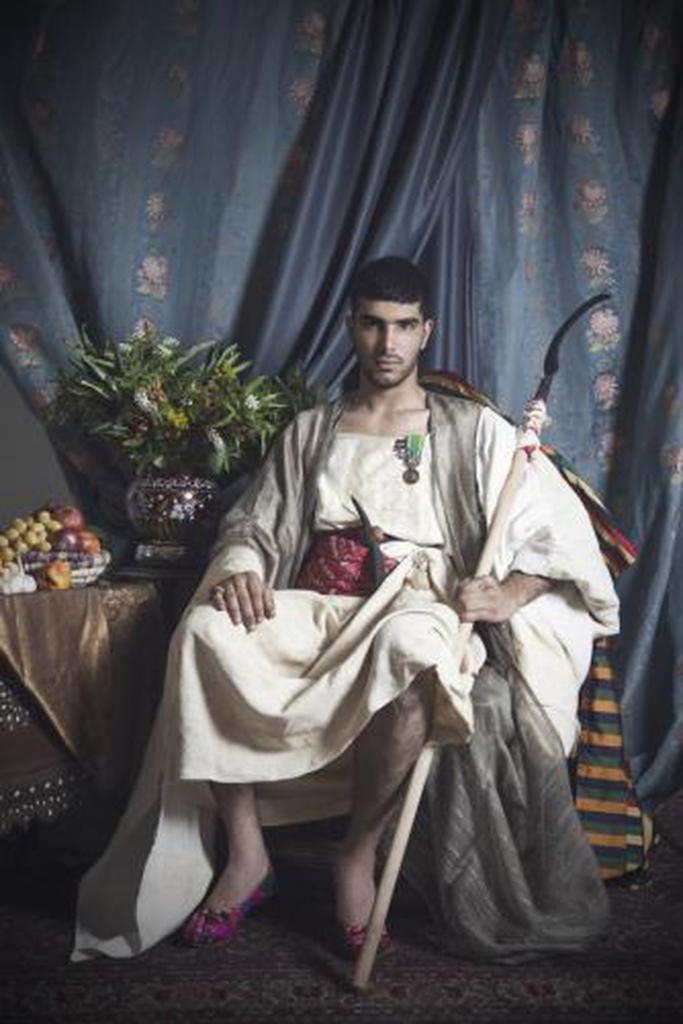

Created by Palestinian artist Omar Joseph Nasser-Khoury, aka Omarivs Ioseph Filivs Dinæ, the design exhibition focuses on identity, gender, history and the materiality of authority in the Palestinian context.

“The Ceremonial Vniform” presents the viewer with imagined uniforms for male officials in the emerging Palestinian state, and it sees itself as the logical continuation of a national project promoted by the Palestinian National Authority that seeks to construct the institutions and appearances of “statehood” with little thought given to changing the existing political conditions of Israeli occupation.

The exhibit comes in response to the 2012 Palestinian bid for a seat at the United Nations, and offers a critical reading of the contemporary Palestinian national movement and the vision of Palestine contemporary political leaders are selling the public. If we create the appearances of an independent state, the exhibit asks, will we become one? If we wear the costumes of an independent people, will we become free?

Utilizing traditional Palestinian fabrics and designs, Omarivs Ioseph Filivs Dinæ also interrogates the discourses of “heritage” and symbols promoted by political leaders. He suggests that these discourses commodify Palestinian culture and reduce it to a mere physical adornment for a statehood project that many fear is reproducing the oppressive system of control that it emerged to liberate itself from.

At the center of these discourses of heritage, of course, is the Palestinian woman and her traditional outfit. While Palestinian men are depicted in active roles as fighters, prisoners, and farmers, women — and their clothes — continue to symbolize heritage and the family, albeit sometimes in the context of the national struggle. Omarivs Ioseph Filivs Dinæ, however, seeks to rectify this imbalance by offering Palestinian men a traditional uniform to wear in their “independent state” — in the process offering a searing critique of a national movement that has negotiated itself into a rut.

Ma’an sat down with the artist in Ramallah to discuss the exhibit, the Palestinian struggle for liberation, and the possibility of the Palestinian Authority adopting the uniform. The following is an abridged transcript.

The evolution and creation of a fixed cosmology of Palestinian national symbols is a process that has been going on for decades. We can look into 1960s and 70s, for example, and see the beginnings of the “Canaanite revival” — which sought to seek ancient origins for Palestinians, just as the Zionists had successfully done for themselves.

These projects of “proving” Palestinian roots largely emerged in response to the Zionist state-building project, which justified its settler-colonial ambitions in terms of proving its supposedly ancient roots to the land. What is the relationship of your work to these projects?

In the past 50-100 years, since the Palestinian bourgeoisie began getting together to have conferences against British colonialism and Zionist migration, very little has changed. The words have become mantras, part of a canon of slogans. This has continued, especially since Oslo and in the last few years.

You live the reality, and you keep hearing the slogans, and you realize how people themselves start talking in slogans. For the past 20 years, symbols have come in the form of martyr posters, the Dome of the Rock, the colors of the flag, Jerusalem, dress, etc. But the problem with symbols is that they become empty. They do not evoke anything but that very shallow feeling of recognition. Beyond recognition, it doesn’t provoke a reaction, it doesn’t provoke thought or a creative or revolutionary response.

It’s become systematic to the point that anything that happens becomes swallowed up in that machine that produces symbols. For example, this young man who was martyred in Birzeit on Feb. 28 — the story is that we don’t know why they killed him. Of course, there doesn’t need to be a reason for the occupation to kill you, but at the same time the reasons become irrelevant. He becomes a number — even for the Palestinians.

It doesn’t matter, he becomes a martyr, he’s a martyr, he’s a hero, he becomes a symbol that doesn’t need questioning. You don’t even question the situation in order to lead to any revolutionary reaction. You follow a set of mantras — you go to the funerals, to the checkpoint, you throw stones, you produce slogans, and that’s it. That’s the trouble with what has become the cause in society — it’s routine. There’s a routine reaction, a set of protocols.

This is in line with this obsession to have a nation, to have a chair at the UN, at the country club. And all of this needs a uniform!

These symbols have become so integral, so important, that we need to establish a uniform for this nation. So in these two portraits, the garments have been made as a standardization of these symbols. The symbols of costume, of dress, of slogans. They all touch on different things. the shirt for example, is made up of Arafat’s 1988 speech in Algeria, the declaration of the Palestinian state, and his 1974 speech at the UN.That’s what this project talks about — the need for symbols, as if they are the redemption of Palestinians.

Would the uniforms you have created ideally be uniforms for bureaucrats, or soldiers, or just a general national garb?

Since the idea that there are all of these things is so disgusting to me, I didn’t go so far as to figure out what rank the uniform would be for. That would be another project, and I’m not so keen on that.

So how would you feel if an official body decided to adopt this costume?

That would be the irony, because I’m not creating these as caricatures, I’m making them look as serious as possible to the point that people look at them and need to wonder — are these real people at real times made for real occasions? Or is this just a fashion shoot?

It’s important for me to make that confusion because we are that point — we’re confused. Because the PNA does now have a ceremonial uniform, garb, symbols, logo and coats of arms and ranks — it’s a joke! It’s real but it’s not real. Who’s it for? It looks legitimate but it’s totally unreal.

It seems unreal that the authorities could potentially adopt these uniforms, but I’m sure 20 years ago, if people imagined the situation that Palestine is in today, it would also seem completely unreal.

Could they have ever imagined that there would exist a kind of Palestinian police force that can’t actually do anything? Or Palestinian security forces that have to retreat every time Israeli soldiers come down the street?

The trouble is that Israel — as an establishment, an army, and as a nation — has so much influence over our imaginary as Palestinians, as it is the first example of a nation, especially of a European nation, that we have contact with (as opposed to the British, who came and left, and didn’t create a discourse as clear as the Zionist discourse). It is to an extent the only reference that many people have of what a country should look like.

The current uniforms of the Palestinian police, the color of the police and the army, are equal or identical to the Israeli uniforms. A lot of people wouldn’t be satisfied if it were otherwise. For them, emancipation is to become the enemy, rather than becoming something else, or better, or totally dismantling this pedigree.I’m also trying to say here that we need to be very careful, we are turning into what we have always tried to resist. These guys are not just only threatening us, they’re informing our imaginations and our discourse in a way that has made us unaware of who we are anymore.

As well as the fact that the reproduction of Zionist apparatuses of control is not necessarily an emancipatory path.

Exactly. That is of course besides what the PNA actually does for the Zionist establishment. But I’m talking about how the way this becomes acceptable, in the minds of people — besides this idea that people are depressed and defeated, there’s always this psychological warfare and indoctrination and features and symbols that are not being filtered by people, that people aren’t aware.

They’re allowing these things to pass. To a considerable extent people aren’t willing to challenge that. that doesn’t come from nowhere or from basic fear, it comes from this acceptance that we need to have those things.

Maybe it’s a generational issue, but I think that there is also a sense of pride in the creation of a police force. People who 20 years ago couldn’t fly a flag get caught up in achieving those symbols of nationhood.

But that’s failure — that flying the flag is a priority, over the freedom to fly a flag itself. This is the trouble. The achievement comes from having the choice of being able to fly a flag, not in the act of flying the flag. That’s where there’s a confusion. People are obsessed with flying flags because they can. Not because they have the choice to.

This becomes the subtext for all of this: “20 years ago we couldn’t do this so its an achievement that now we can.” But it’s not about being able to or not, it’s about asking: why do we do these things?

We are fighting for self determination, and these are not self determining. We’re just fulfilling symbols and protocols and rituals. The right to self determine is the real struggle. These are not necessary things, these are just symbols and colors and layers that can be made and remade.

But to have the ability to choose, to determine things for our own self, without the influence of the occupation, or referring to systems of value which are warped — this is the true revolution. This is the true Palestinian cause.

“Ceremonial Vniform” is on display at the Birzeit University Museum until June 20. The museum is open daily, except Sundays and Fridays.For updates, check the designer’s website, www.omarivsioseph.com, or follow the progress of the exhibition on his blog, http://omarivs.tumblr.com, or on twitter @OmarivsIoseph.