Originally published on Jadaliyya on July 7, 2015.

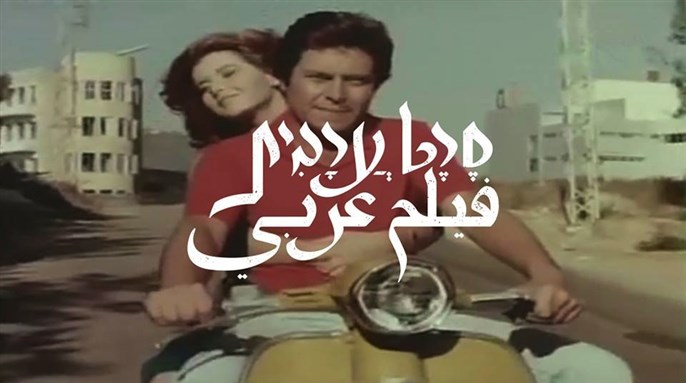

Eyal Sagui Bizawe is an Egyptian-Israeli artist who with Sara Tsifroni co-directed the recently released documentary “Arab Film”. It tells the story of the social and cultural phenomenon of the weekly Arabic-language movie that was for decades shown on Israeli television every Friday evening.

In an age where the only television stations were public terrestrial broadcasters transmitting for only a few hours a day, the Israeli state did not issue its first broadcast license until 1966 and transmission began only in 1968. Prior to the 1967 War, successive Israeli governments had rejected the establishment of a television station on the grounds of protecting public morality. They reconsidered for the express purpose of luring newly-occupied Palestinian viewers away from Egyptian, Jordanian and Syrian stations, and Israeli television thus initially broadcast almost entirely in Arabic. The official Israeli official channel nevertheless caught on among Israeli viewers as well. Friday nights, ironically the start of the Jewish Sabbath, became a highly-anticipated time for families of all backgrounds — Mizrahi, Palestinian, and Ashkenazi — to gather and watch movies together.

The phenomenon is widely known in Israeli society but little remarked upon, and there has ever been very little discussion about how peculiar it is that in a society where expressions of Arabic culture and language were highly discouraged and even punished among Jewish immigrants from Middle Eastern countries as well as native Palestinians, the government broadcast films on a weekly basis from Arab countries with which Israel was in a state of war.

In this interview, Bizawe talks to Alex Shams of Ajam Media Collective about how the documentary came about, his experiences growing up Egyptian in Israel during the 1970s, and the complexities of Mizrahi politics and anti-Arab racism in the country today.

Alex Shams (AS): How did the phenomenon of watching the weekly Arab film begin in Israeli society, and how widespread was it? Were people surprised that Israeli state television’s first major decision after its creation was to screen Egyptian movies?

Eyal Bizawe (EB): From the beginning of Israeli television in 1968, it used to broadcast every Friday afternoon what we used to call the “Arabic movie,” which was mainly Egyptian movies as well as a few Lebanese and Syrian films. We used to sit every Friday afternoon to watch it every week, and when I say we, I mean “we” — the most general “we” you can imagine. I grew up in a very mixed neighborhood — Ashkenazim, Mizrahim, people from many different places — and I remember that at that time our entire neighborhood would go silent. From every balcony and window, the only thing you could hear was the sound of the Arabic movie.

It was an obvious part of life, every week. No one ever asked anything about it, it was taken for granted as normal. We just knew it was there. I’m not saying that everyone in Israel used to watch it, but from all the different groups in Israeli society there were people watching it. There was nothing else on TV like that reached such a mass audience.

But how come it was so obvious to us, a part of our reality that we accepted without question? Egypt was our biggest enemy until the late 1970s — to the extent that they used to call Gamal Abdel Nasser “Hitler on the Nile” and we were sure that the Egyptians were going wipe Israel off the map. And yet, we used to watch an Egyptian film every week. In 1973, war broke out for almost a month and Israeli soldiers were on the front in the Sinai desert confronting Egyptians, and yet their families were sitting at home watching Egyptian films. Why did no one ever ask themselves: “Why do we watch the movies of the enemy?”

Especially at that time, anything having to do with Arabic culture was not only of the enemy, but it was also automatically inferior, not even considered culture. You couldn’t even hear people listening to Arabic music publicly. They might do it in their home, quietly so the neighbors couldn’t hear. But suddenly, through a government policy, every week we were watching Arabic films!

The other question was: How did we get the film? How come no one ever asked, this question? If there is no relationship between Israel and Egypt, how could we be getting them?

AS: An interesting point you raise in your documentary is how the screening of the Arab film is deeply connected to the beginning of Israeli television more broadly, and one could not have been possible without the other. Could you speak a little bit more about that history?

EB: In the 1960s there was a proposal to launch an Israeli television channel, but Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion rejected it, just like he refused to allow the Beatles give a concert here. He argued that TV would corrupt the young generation, so he refused to allow the government to begin broadcasting.

And yet, while Israel had no TV, in the “primitive” Arab World they had it. Toward the end of the 1950s and into the 60s, there were Arab channels in Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan. And once we occupied the [Palestinian] territories in 1967, we suddenly had a million and a half Palestinians who had been exposed to “Arab propaganda.” Israel decided to also start a channel in order to expose the Palestinians to our hasbara, how we “explain” ourselves. We didn’t call it Israeli propaganda, because in the Israeli mind we of course don’t make propaganda. Only Arabs do propaganda, we just explain!

The original idea of creating the Israeli channel was to have an Arabic-language station, with three hours broadcast in Arabic and one hour in Hebrew, for a total of four hours a day. The idea of broadcasting the Egyptian movie was done in order to attract Palestinians to watch the Israeli channel. The movie – by pure coincidence of course — was immediately followed by the news.

AS: But how did Israeli television actually get the physical movie reels into the country from abroad?

EB: The ones who worked in that field were Jews from Arab countries that really, really loved Egyptian cinema, and they did their job out of love. But the idea of the channel and of the Friday films came from above. The Arabic movie was never meant to be for an Israeli audience — it was intended to reach Arabic-speaking Palestinians — and so at the beginning there was not even translation. Then Jews started writing letters demanding subtitles, but the manager of the Israeli broadcast channel opposed this. After they really started to put pressure, the issue came to the Knesset, and after many debates they forced him to subtitle the films.

Then, after Hebrew subtitles were allowed, a movement started to change the time of the film. It was originally broadcast at 6 p.m., but religious people started petitioning to have it broadcast earlier so it wouldn’t interfere with Shabbat.

When they started Israeli television to target the Palestinians, no one ever imagined that Israelis would be the ones to fall in love with Arab films.

AS: What kind of documentary did you set out to make?

EB: It was difficult for us to find the right voice and to decide how we want to tell the story. It has great potential to become a very nostalgic documentary. But I wanted to go there because nostalgia is not only a bad thing. It can be, depending on how you use it, but it doesn’t have to be. I wanted to use nostalgia in order to attract the audience, because we knew that once you bring up the topic with an Israeli of any background — Ashkenazi, Mizrahi, Jew or Arab, religious or not — you’ll find an interested audience. Even very religious people used to watch the movie every Friday afternoon, even though they were not allowed to [on account of the Sabbath]. People used to make excuses utilizing the halacha [Jewish religious law] to explain or justify why they were allowed to turn on the TV on at that specific moment. These same religious people refused to even light cigarettes on Shabbat! As a phenomenon, the Arab Film is beautiful.

But we did not want the documentary to be only nostalgic. We wanted to be critical, and we wanted to find answers and to understand how we watched the film, as well as how we got the film.

AS: How did Israelis watch the film?

EB: It is true we used to watch it every Friday afternoon, but it’s also true that we used to look up to it. But now the “we” is broken, it’s not the same “we” as the one with which I started the conversation. Because my parents used to watch it as their cinema, as their culture. I think the younger generations, the sabra [those born in Israel] who created and today control hegemonic culture in Israel used to watch it with very cynical glasses. They used to watch the Arabic film, but in order to laugh at it, to make fun of it, to mock it.

The biggest evidence of a cultural turning point regarding the Arabic movie occurred in the middle of the 1980s when the comedy program Zehu Ze! (“That’s It!”) satirized it. Zehu Ze! was the most popular weekly comedy program for many years and was watched widely among the Israeli public, though much less among Palestinians or older Mizrahim. It was broadcast during the children’s programs but gained a wide following. In the 1980s they made a program mocking the Arabic film by parodying a number of its themes that were quite common and considered over the top and emotional. And until now, this episode was the most successful episode in the show’s history.

It was so successful that today, when you talk to people about the Arabic movie, people from my generation quote from the program and not really from the Arabic movies themselves. The Arabic movie was very stereotypically represented, and it was funny. But I think this also stopped us from examining the phenomenon and trying to understand our relationship with the Arabic movie.

And when I say Arabic movie, I mean the Arabic movie as a symbol, not just as a movie. It was a little window opened up for Israeli society — especially Jewish society — to know better the region around it. But since we didn’t give up our cynical glasses, we didn’t really see it. We watched it, but we didn’t see.

AS: There is also a generational difference that is coming into play, as you describe between sabras and older Mizrahim. You have a generation of people who lived in Arab countries, who are familiar with Arab culture, and for whom as you said the Arabic film was just a movie. But the situation was different for their children, who were acculturated into an Israeli society where central European norms were hegemonic and for whom this movie was seen not just a movie but specifically an Arab movie.

EB: It’s important to remember that a similar process occurred with young Arab people. But at the same time, they still had the privilege of knowing the cultural codes in the film and being able to understand what they were seeing.

For Israelis, most of Egyptian cinema — well, let me stop there and quote what a number of people said in the movie: “We didn’t see it as a cinema, it was not cinema, it was something folkloristic, for home. Cinema is Federico Fellini, Jean-Luc Godard, and Pier Paolo Pasolini. Egyptian movies are something cute.” We knew none of the names of the directors, we didn’t know who the Fellini of Egyptian cinema was, and maybe we didn’t even need to know the Fellini of Egyptian cinema. We don’t know who Youssef Chahine is, or Mohamed Khan, or Atef El-Tayeb, or Hussein Kamal or Henry Barakat. We don’t know these names, and they mean nothing for the majority of the young generation of Israelis. We didn’t see it as cinema.

We called it “the Arabic movie.” It was a genre, no levels, no nothing, it was all the same for us. I asked the director and the scriptwriter of Zehu Ze! if they used to watch the Arabic movie and they said no. So I asked them how they managed to parody it so well.

They told me: “We saw one film before we wrote the script. And if you’ve see one, you’ve see them all.” For us, there was no difference between quality and no quality. The Arab movie was a genre with nothing to discuss, nothing to learn from, nothing to look at, and nothing to research. There were times when the Egyptian cinema industry was the third largest in the world after Bollywood and Hollywood. And you don’t study it? Not even one class in the university? This is crazy.

AS: What were your goals with the documentary?

EB: We had too many goals, and maybe that’s why it took us six years to finish it. We wanted to make it nostalgic but critical, which are two goals that are supposed to be contradictory but are not necessarily so. It’s important to have nostalgia but it’s important to know how to use it.

Sometimes nostalgia is just a way to remember a beautiful past and all that bullshit. But sometimes nostalgia is about saying that what we have now is worse than what we had before, it’s about saying that we prefer something else. Because what we have now is awful. Sometimes nostalgia can be used in order to say critical things about the here and now.

AS: When you say what we have now, what do you mean?

EB: What we have now is that we have a wall. We don’t have any more Arabic on the Israeli channels, and the little that is there is definitely not very popular. There are kids who don’t know what the Arabic language even sounds like. My generation grew up on kids’ programs in Arabic. But now it doesn’t exist anymore. The wall is not a wall in order to defend ourselves, obviously. But it’s also not just a wall in order to put Palestinians in a cage. It’s a wall so that we won’t watch, we won’t see, and we won’t hear. The removal of the Arabic movie is just a symbol of that. But it says something more, much more about Israeli society.

Our third goal was to say something about Egyptian cinema. Even though it’s not a documentary about Egyptian cinema — it’s about the Israeli phenomenon of watching Egyptian cinema — we wanted to help people understand what they’re missing by showing them a bit of Egyptian cinema in the documentary.

The fourth goal was the most difficult for me, as it was to try and find the voice of the documentary — which is actually my voice. Sara and I directed it together but I’m actually the one in the front, and we start with my own story and my own family. Even though nothing in the documentary is new to me, I still had to go through the process of learning again in order to understand how my own story combined with that of society, and to understand how my story is part of that. I originally didn’t want to talk about my family, I wanted to talk about the Israeli phenomenon, but it took me time to understand that actually my own story is the Israeli phenomenon.

My parents were born in Egypt, and I grew up in Bat Yam and since I was a kid I spoke Arabic to my grandmother, who didn’t speak any other language. My parents spoke French, Arabic, and Hebrew all together, but my grandma spoke only Arabic.

Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, outside my house Egypt was the greatest enemy, and inside my home Egypt was Egypt. It was a culture, humor, jokes, and language. There was a very big dissonance for me, even if I didn’t know it was a dissonance. But I was always asking questions, because I didn’t understand how come my parents came from this place that wants Israel off the map but at the same they’re telling me stories about their great lives there. I started asking myself, “How come we speak Arabic and yet Arabic is the language of the enemy?” There was a kid in the neighborhood that once heard me speaking Arabic to my grandmother and asked me: “You’re Arabs?” and in response I told him “You’re an Arab, and your whole family is a bunch of Arabs!” We never spoke after that, both offended.

But it was only a few weeks later that we were watching an Arabic movie on the Israeli channel with Leila Murad [a famous Egyptian Jewish actress who converted to Islam]. My mother remarked, “Wow, it’s Leila Murad!” I was shocked and asked, “How do you know her? I knew my mom recognized Marilyn Monroe, Sophia Loren, Grace Kelly and the like. “But how do you know an actress in the Arabic movie?” I asked. And she said, “Oh, she’s the cousin of your grandmother!” And I was like “WHAT?!” I became convinced that we are Arabs and that my parents are concealing this from me. The neighborhood kid asked me if we’re Arabs, and now my mother was telling me we have relatives in the Arabic movie! I remember that I had a lot of questions, all the time. I found myself very attracted to the Arabic language, to Egyptian movies and Arabic music, which my parents never listened to at home, even though my grandmother did. I was the first to bring a cassette tape home in Arabic.

AS: How did they react?

EB: My parents were surprised. I remember the first time my mother understood that I understood Arabic. She told my father: “Shlomo, the kid speaks Arabic!” Not in a bad way, but they were surprised. I was supposed to be their most Israeli child.

We are four brothers — three with black hair, but I was blond. They were all born with the name Bizawe, but I was born with the name Sagui, a very Hebrew name. I am the only one in the family who brought back the Bizawe name.

AS: Your family changed their name?

EB: Before I was born, our father changed our name from Bizawe to Sagui. All my brothers were born Bizawe and they became Sagui, but I was born Sagui and I later added Bizawe.

AS: Why did they change it?

EB: My father used to work in a bank and had many clients, and saw that a lot of people were changing their names to Hebrew names. He noticed that many siblings from the same family had different names and he didn’t want that in his own family. So he said, “Let’s do it before they change it, so we all have the same name.”

I was supposed to be the most sabra kid — blond and named Sagui. And with a name like Eyal Sagui, you can only end up an army pilot. And yet here was this Arab, speaking Arabic and listening to Arabic music. I always felt some kind of dissonance, but didn’t know exactly what it was or what to call it. I didn’t know what it meant, or what it said about me or my family, or if it said something about society.

But I saw that it was not only me or my family that were afraid to be Arabs. I think it’s Israeli society that is really afraid of being a little bit Arab. All the time we talk about how different we are, while I see how many things we have in common. Not in the sense of coexistence and all that bullshit, but in terms of how many things we do have in common. They tell me look at Hamas over there, but I look around and see what we’re doing and I see a lot of similarities. Not exactly the same, it’s never exactly the same, but you always compare between things that are not identical. Similar, but not identical.

AS: How did your family members react to your work on the documentary?

EB: I have an aunt named Aviva, or Toua, who is shown in the documentary. She was born in Egypt, but her son was killed in the 1973 war fighting against Egypt. She’s politically right-wing, but in the documentary she talks about how she couldn’t live without Egyptian films. She considered them her life, even while other Israelis today mock Arab films. But for her, it was her life, even though her son was killed by the Egyptians.

And her favorite movie was this horrible, anti-Semitic film called “Girl from Israel.” Now I don’t use that term lightly. I don’t think everything critical of Israel is anti-Semitic. But this film actually is anti-Semitic, bringing in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and such tropes. And yet, this woman, who calls herself fully Israeli and votes right-wing, loves this movie. Why? Because in the film there is a family that lost their son in the 1967 war, and she identifies with them.

AS: But they lost their son on the other side right?

EB: Yes, it’s an Egyptian family. I asked her, “Do you think you make peace with them when you watch it?” She told me: “No, it think I made peace with them a long time ago. But I do identify with them.” And then I asked her, “Did you ever see Egypt as an enemy? “ And she looked at me and said, “Not really, never. Never.”

“But they killed your son?”

“You know, whatever happened, I love them,” she said.

“But you’re Israeli,” I told her. “You love Israel!”

“I’m 100% Israeli, I agree. But you know whenever I talk to me friends, I always speak as an Egyptian, I always tell them I’m Egyptian.”

A lot of this was obvious and made sense to me. But I realize that very few people have heard this, or realize that this is how things are for a large section of Israeli society. I think in a way it’s a representation of a very, very large group of Israelis whose voice in the media is usually yelling, “Kill the Arabs!” But I can hear, even there, something more than that.

They might say awful things, but they don’t hate. Just like my aunt that loves this film. When we spoke I asked her,” How come you love this film? It’s anti-Semitic!” and she responds, “Oh, that’s bullshit! Okay, they say it, but they don’t really mean it!”

To be clear, I do criticize racist and hateful speech. And you can hear awful things. Yes, Gamal Abdel Nasser said he wants to destroy Israel and come drink coffee in Tel Aviv. But you really think this is what he thought would happen? We do speak like that a lot of the time. We say a lot of awful things, but it doesn’t always mean that we really mean it or we’re really going to do it.

AS: How do you see the role of Israeli state-sanctioned racism in producing or encouraging anti-Arab racism among Mizrahim, as well as the sense that these two identities – Jewish and Arab – are necessarily opposed to each other and cannot co-exist? How do we understand anti-Arab racism among Mizrahim while taking into account that Zionism, since its inception, has been based on the fundamental binary between Ashkenazi/European civilization and Arab/Oriental/Mizrahi barbarism?

EB: There are a few reasons why many Mizrahi Jews are right-wing. One of them is a need to be more Israeli than any other Israeli. They came here, they look like Arabs, they eat like Arabs, and they speak like Arabs. They want to differentiate themselves from the Arabs by being the most Israeli they can be: by being more religious and more right-wing. This is the obvious answer.

But we have to admit that for many Jews their final years in Arab and Muslim countries were not that good. It’s true that they loved their country and felt at home. But it wasn’t the paradise that many historians want to show. Yes, compared to what happened to Jews in Europe — of course there is no comparison. I would also be very careful not to say it was terrible, because I don’t think it was terrible. I think that anywhere there are different communities, there will be problems. But I don’t think that most of what happened were things that happened to Jews as Jews. There were some, we have to admit — the Farhud in Iraq in 1941, in Sanaa, in Tripoli, in Damascus, in Tehran. There were. But people always want to describe things as Heaven or as Hell. But it’s not Heaven or Hell, it’s a complicated picture. We live complicated lives, and it was exactly the same back then.

Zionism caused major damage to Jewish communities all over the world. But this was true of the national idea everywhere, not just Zionism. Arab nationalism wasn’t able to include the Jews, even though there were Jews who were trying to be part of Arab nationalism. There are books like Yehudi fi al-Qahira (A Jew in Cairo), by Shehata Harun, who was a real Egyptian patriot who refused to leave his country even after the whole community left. He saw himself first and foremost as Egyptian. And yet in 1967 Gamal Abdel Nasser put him in jail because he was a Jew.

I’m not a Zionist, but I do want to be fair. And Zionism is not the cause of all the problems here. It is the idea of nationalism that is the problem.

When the Jews from Arab countries came here, it was very complex for them. Many of them really missed their countries, especially Jews from Morocco. There were demonstrations in Haifa, for example, against Ben Gurion where they yelled: “We want Muhammad V, He is our king!” On the other hand, there were other Jews for whom the experience was a bit different. They didn’t want to go back. But it depends when they came and where they came from.

As the years passed and they remained in Israel, they felt that they had to be part of the Israeli narrative. They started to describe their own history and their own memory in terms of the Jewish experience in Europe — talking about ghettoes, and not about mellah or hara [Jewish neighborhoods]. But these Jews didn’t live in “ghettoes,” and their old neighborhoods are not the same at all. Attacks on Jews were being called “pogroms.” But these are all terms that historians used in order to describe the experience of Jews in Europe. But it’s not the same.

When I was a kid, I always wanted to hear stories about my parents’ experiences in Egypt. Because it all seemed very strange to me that they came from Israel’s biggest enemy but described a very nice life there. So I was looking for bad stories, in order to feel part of the Israeli history and narrative. I really wanted to know that someone in my family had sacrificed in some way. I wanted to know that we also have a Zionist hero.

There was one story my mom told me when I was young that really nourished my imagination. She called it “Black Saturday,” and she said it happened at the beginning of 1952, when all the “Arabs” burned the homes and shops of Jews (in Cairo). She remembered she was 12 years old how they had to run away to their homes, and turn off all the lights and hide. When the crowds came to the building, their neighbor told them that there were no Jews in the building. My mother remembered the sky was red from a huge fire that night. For me, this was like “Wow, my mom was almost killed in a pogrom!” This was great stuff for an Israeli kid!

Many years went by and I came to know a lot about Egypt and its modern history, but for some reason I did not find any information about that story. But one day while in Cairo I went to buy a periodical I really love, Masr al-Mahrousa, and I found an old edition that was dedicated to the big Cairo fire of 1952.They called it “Black Saturday.” And apparently what happened that day was that British soldiers killed more than 50 Egyptians, and out of outrage and anger, the Egyptians decided to demonstrate and burn everything that had to do with foreigners. Not with Jews, but with foreigners. But since a lot of Jews in Egypt weren’t Egyptian but were foreigners, their places were also damaged. But the demonstrators didn’t go into Harat el-Yehud (the famous Jewish neighborhood of Cairo) and they didn’t burn synagogues.

It’s not that my mother was lying. My mother was 12 years old, and this is what she remembered. When she came to Israel, she heard a lot of stories like that from other places in the world, and she said, “What I remember is the same”.

Regarding the left, I think one problem for Mizrahim is that they often felt that Ashkenazim on the left ran out to go look at Palestinians but refused to look at them. The Ashkenazi left doesn’t want to hear or listen or know anything about Mizrahi Jews. The minute you say something about Mizrahi Jews, they say, “Oh come on, maybe there was some discrimination back in the 1950s but not anymore.” Well look at the education system, look at what is happening in the towns on the border where most of the residents are Mizrahi or, more recently, people from Russia and Ethiopia. There is something very annoying for a lot of Mizrahi Jews that the Ashkenazi left are going hand in hand with Palestinians but at the same time are ignoring them.

I think back to my aunt Aviva, the Egyptian woman in the film who talks about being fully Israeli but also fully Egyptian in the same sentence. After every screening of the documentary, people come up to me to ask about her. I think they see these contradictions, this struggle inside of Mizrahi Jews who feel connected to their culture and their first motherland, but at the same time really want to be Israelis.

There is something very human in saying one thing and then in the same sentence saying something totally contradictory. We live in a period of big ideologies: left and right, Zionist and anti-Zionist, nationalist and anti-nationalist. But in our everyday life, we do things that sometimes don’t fit what we believe. I think that we have to think about that. There are little truths in every narrative and I think it would be better to acknowledge those little truths, as little as they are.

I would like to be able to say very easily, I’m anti-Zionist and I’m anti-nationalist. But it’s not that easy. Specifically, I cannot say to the Palestinians – a people who still don’t have their independence – that I’m anti-nationalist. How dare I stand in front of them and tell them “national identity is bullshit”?

And now if I don’t tell them national identity is bullshit, how can I stand in front of my family telling them Zionism is bullshit? I will tell them that Zionism is another level of colonialism, and that we have to acknowledge this. But to erase it? It’s a bit more problematic for Mizrahi Jews who want to keep in mind the Palestinians as well as their own families. It’s very complicated.