Originally published on Middle East Eye.

Whether or not Islamophobic motives are found, the reaction underscores feelings of an existential threat gripping some US Muslims

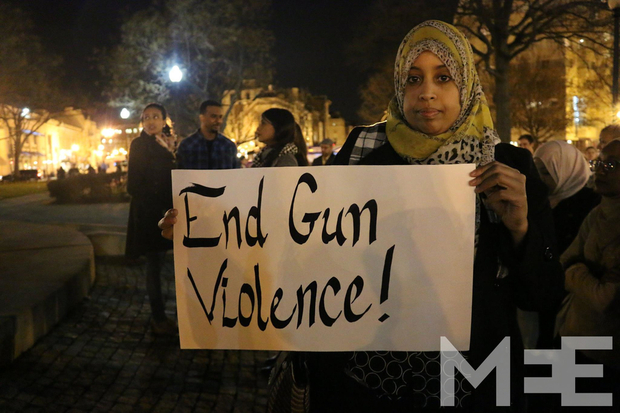

Muslim Americans hold a vigil in Washington following the murders (MEE/Ilana Alazzeh)

CHICAGO, United States – The mysterious killings of three young men of Sudanese heritage in Fort Wayne, Indiana last week shook the Midwestern town of 250,000.

But the murders, which police have said were carried out “execution-style,” have also created shock waves across the country, particularly in Muslim communities.

Already reeling from a surge in Islamophobic rhetoric by politicians over the past six months and a spike in hate crimes, many Muslims fear that the official uncertainty regarding how and why the three youths were killed may be hiding hate-based motives.

Activists held vigils for the three victims – Muhannad Tairab, 17, Mohamedtaha Omar, 23, and Adam Mekki, 20 – across the country this week, and many on social media have changed their profile pictures in memory of the youths and spread the hashtag #OurThreeBrothers.

“Everyone is on edge, and then an incident like this happens and everyone is left wondering what they’re going to do now,” said Gohar Salam, a local doctor who is also the president of Fort Wayne’s largest Islamic centre and school.

Although police and the families of the youths – two of whom were closely related – have cautioned the public not to jump to conclusions, the speed at which the case has become a rallying cry for young Muslims hints at the community’s deep unease amid the rise of controversial figures like Republican presidential frontrunner Donald Trump who have helped fuel Islamophobic sentiment.

Whether or not Islamophobic or anti-black motives are found in the killings, the reaction underscores the sense of an existential threat that has gripped some Muslim Americans in recent months.

The bodies of the three men were found east of downtown Fort Wayne on 24 February in an abandoned house that was sometimes the site of parties held by young people.

All three of the young men were children of Sudanese immigrants; two of them came from a Muslim background while the third was Christian.

In a press conference on Tuesday, family members said they had escaped war and ethnic cleansing in the Darfur and Nuba regions of Sudan by emigrating to the US, and managed to settle in this mostly white Midwestern metropolis, which is dotted by large immigrant and refugee enclaves.

The family has focused their response on the need to end gun violence broadly, asking the public to “stop the senseless killings of young beautiful souls”.

But some worry that this is not just another case of America’s unhealthy obsession with guns.

Salam told Middle East Eye that “when the news first broke, the biggest concern was that the crime was Islamophobic”.

“But luckily we live in a town where we have strong relations with the police, the authorities and the FBI,” he continued. “After their initial assessment that there was no evidence of hate involved,” the families accepted that premise, he said.

There was a strong possibility that the men “were just at the wrong place at the wrong time,” he added, noting that the place where they were found was “not considered very safe”.

Echoes of a massacre

But as news of the killings spread across the country over the last week, many noticed parallels with the murders of three young Muslims almost exactly a year before.

In that incident, three students, including two women wearing the hijab, or headscarf, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill were shot dead by a neighbour.

Police said the killings were caused by a “parking dispute” that escalated out of control.

But one of the victims’ fathers noted that his daughter told him beforehand that the neighbour “hates us for who we are and how we look”.

Many across the country argued that last year’s incident seemed to have strong Islamophobic undertones. In the year since then, hate crimes against Muslim Americans have risen amid the increasing visibility of conflicts in the Middle East, the Islamic State attacks in Paris and a mass shooting committed by a Muslim couple in San Bernardino, California last November.

The domestic political climate, meanwhile, has worsened the situation for Muslims, many of whom feel the community is under siege. Presidential hopefuls like Trump and Senator Ted Cruz have seized upon Islamophobic and xenophobic rhetoric for political gain.

Only a few days before the bodies were found in Fort Wayne, Trump told a large crowd of supporters a fictitious story that he believed to be real about dipping bullets in pig’s blood in order to murder large numbers of Muslims, suggesting approvingly that the strategy worked. In the same speech, he also hailed torture as an effective practice, only a few weeks after calling Cruz a “pussy” for not fully endorsing it.

This was the context in which many Muslim Americans interpreted the killings this February.

“A lot of folks immigrated to this country because of the American dream, and I still believe this is best country,” Salam told MEE. But because of the Islamophobic climate, “there was unease developing in their minds which had not yet come to the surface”.

He noted that many members of the community, especially women wearing the hijab, were being subjected to violence and verbal harassment on a much more frequent basis than ever before, and that Muslims were increasingly concerned about their well-being in the US.

Activists respond

Despite the lack of certainty regarding the motives behind the killings, activists across the country have organised vigils and more are being planned.

Some activists have seized upon the lack of media attention and public outrage over the deaths, highlighting that regardless of the motives, the relative silence surrounding the incident shows the media care less about black or Muslim victims than their white counterparts.

Only days before, the killing of six people in a mass shooting in Michigan and three in Kansas made national headlines. Activists have contrasted the reactions to those killings – in which the majority of victims were white – with the muted response to the killing of three black immigrant youths. Indiana’s governor, for example, who frequently tweets out condolences for similar incidents, failed to do so in this case.

Afaq Mahmoud, a cousin of two of the slain men, pointed out that internet commentators had “dragged their blood through the mud” by accusing the victims of being gang members or suggesting that they somehow deserved to die for being black or Muslim.

“Apparently lives are only worth mourning when they look a certain way,” she said. “Apparently lives are only worth mourning when they live a certain way. Apparently lives are only worth mourning when they pray a certain direction. Apparently some lives aren’t worth mourning at all.”

While the mainstream media treats white American lives as worthy of mourning and “innocent until proven guilty,” activists charge that for most people of colour in the US it works the other way around.

Hoda Katebi, a Chicago-based Muslim activist who organised a vigil for the Chapel Hill killings last year and who is helping to organise one for Fort Wayne as well, told MEE that it was crucial for “blacks and Muslims to come together and have collective healing”.

“It’s more than mourning – it’s about creating a space for healing, for people to feel like they’re not alone,” she said.

“We want to use this as a space to mourn and celebrate their lives, but also to talk about Islamophobia and anti-blackness and other types of violence in the US,” she continued.

“Regardless of the cause of their death, the fact that media selectively chooses whose lives are worthy of attention and public mourning tells a lot about Islamophobia and anti-blackness in this nation.”

Noting that she had experienced an uptick in harassment and violence as a Muslim woman who wears the hijab, Katebi stressed that Muslims and black people in the country were being targeted because of Trump’s rise to prominence.

“We laugh at him and think he’s funny, but he’s getting a lot of media exposure and he’s reaching large population. It’s scary to think people are being persuaded and are acting on these impulses,” she said.

Back in Fort Wayne, Salam said the community appreciated the national support but more than anything the families were requesting calm until more details came to light.

“If the rhetoric of hate settles down, we can live in harmony and peace,” he told MEE.

“It’s very sad how things are [in the US] right now,” he continued. “An entire generation is being scarred by hate.

“This is going to hurt the fabric of our society. In the end, we all have to live together. America is great, and we have to make it greater.”

Despite the optimism, the fear that things will only get worse is pervasive.

“I would really be scared for this country if Donald Trump actually became president,” Salam told MEE. “The United States of America deserves better.”