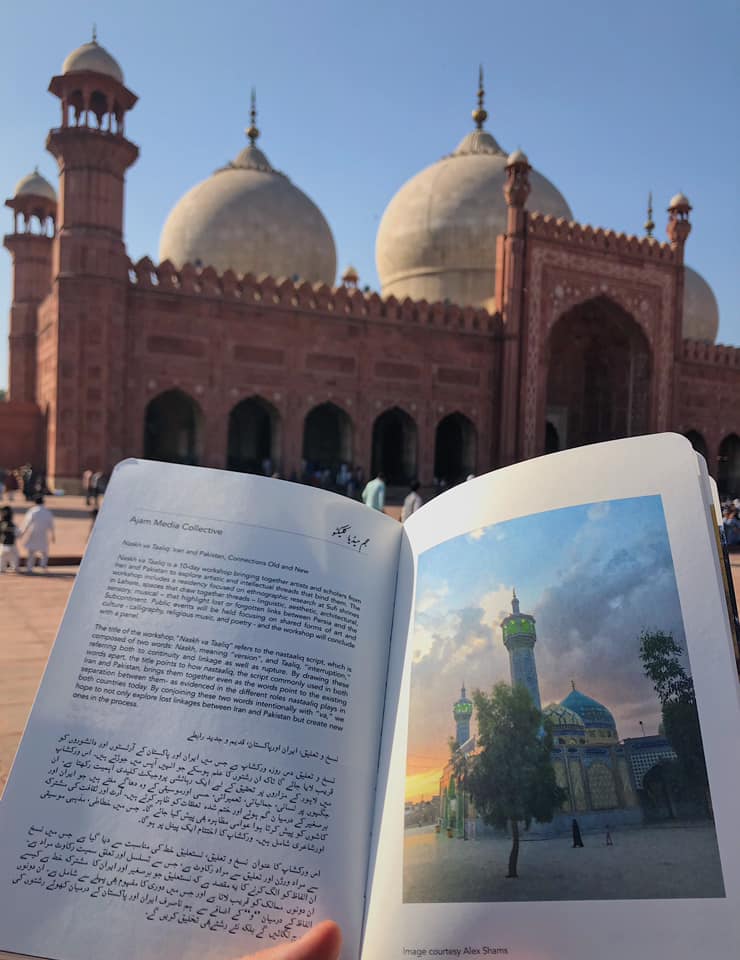

In February 2020, I was invited on behalf of Ajam Media Collective to organize a workshop at the Lahore Biennale. Entitled, “Naskh va Taaliq,” the workshop explored cultural connections between Iran and Pakistan, including through ethnographic research at four religious shrines in Lahore. These reflections were written a year after the workshop, to be published in the Lahore Biennale 02 Reader.

***

For Iranians, Lahore is both familiar and totally unknown. Persian poetry is replete with references to the city and its past. But it is shrouded in mystery, part of a constellation of lost geographies whose names evoke beauty but whose presents are unfamiliar: Samarqand, Kashgar, Bukhara, Lahore… Perhaps Pakistanis have a similar feeling upon hearing Isfahan or Shiraz. Their names echo on our tongues. But in the world of borders and Kalashnikovs we find ourselves in, they feel more disconnected than ever before.

Whatever sense of distance we once felt dissipated upon booking our tickets from Tehran to Lahore. We departed from Tehran to arrive a few hours later, to our delight, at Allama Iqbal. In Iran, Eqbal-e Lahori (as he is called) is a legend studied by every schoolchild. We arrived in an unknown land only to be greeted by a beloved poet who felt already a part of us. Suddenly, the “Lahori” in Iqbal’s name came to life; no longer frozen in the past, we could imagine Lahore as part of our present and future.

From the moment we arrived, we were confronted by a land at once unknown yet familiar. All around us flowed nastaliq. In Iran, this script is limited in public usage – poetry, religion, or decorating official buildings. Seeing this script in Lahore above our heads created a sense of deep intimacy with our environment. Although we could not understand the conversations around us, the texts invited us to read them.

We marvelled at the words we saw: bayn-ul-qowmiyati amad. Written in Urdu, a language none of us understood, it was completely legible, though unlike anything we would say in Persian. It read like poetry – instead of “international arrivals,” in Persian it said, “between different nations, an arrival.” Urdu, like Lahore, was a part of us we had never known before. We began to understand that for many Lahoris, Persian and Iran evoked similar feelings.

For the Lahore Biennale, I organized a 10-day workshop bringing together artists and scholars from Iran and Pakistan to explore connections between these two neighboring lands, on behalf of Ajam Media Collective. We explored the shared threads that bound us in the hope of building a collective future in which we were no longer strangers but friends, companions, lovers, and comrades.

We named the workshop Naskh va Taaliq. Nastaliq is a compound of two words – naskh, meaning “version” or “copy” and taaliq, meaning “suspension” or “interruption.”

It seemed an appropriate metaphor for the relationship of Iranians and Pakistanis – one based on a long history but which today is defined by our separation, our distance, our doori more than anything else.

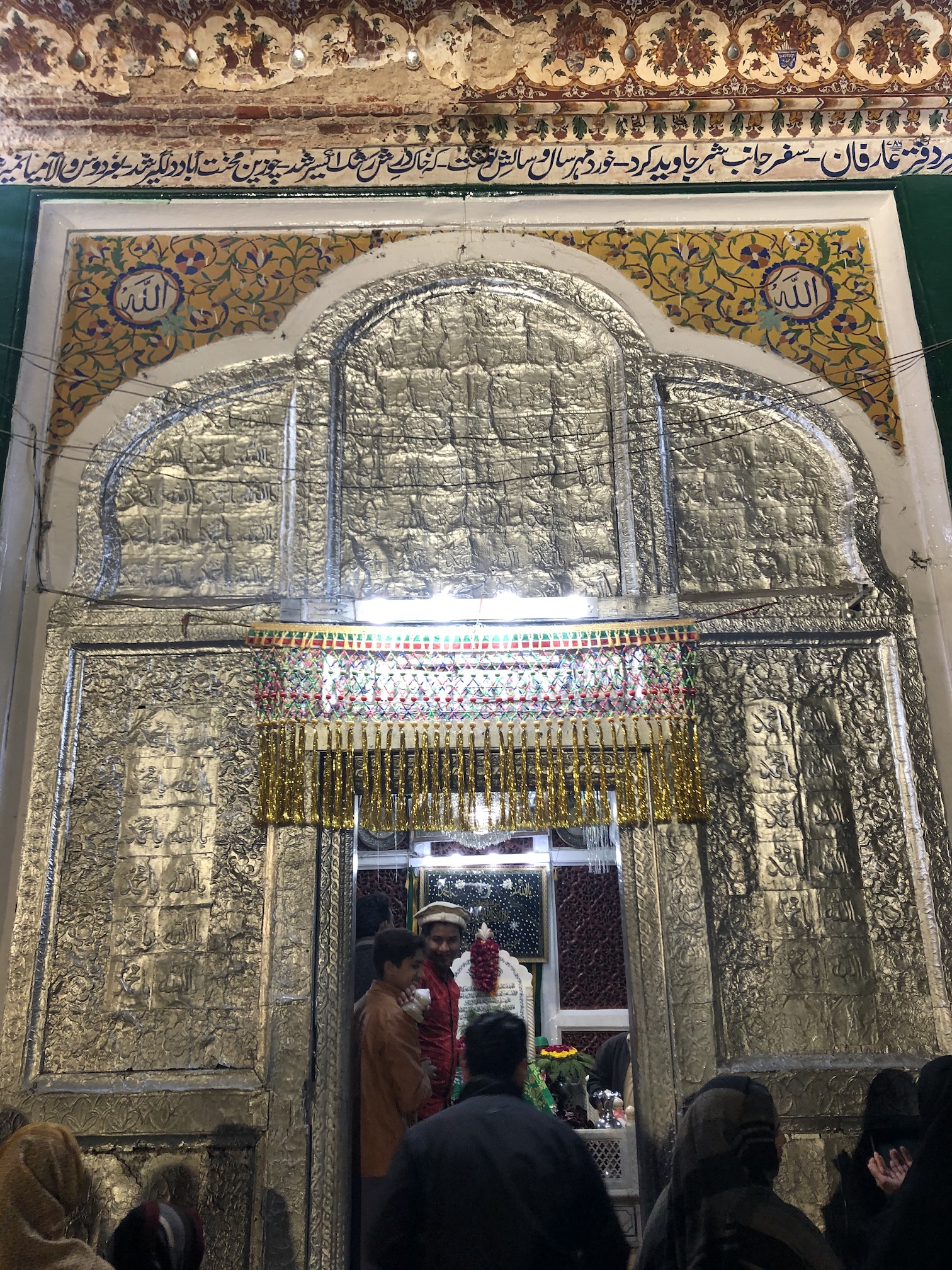

The workshop consisted of a 10-day residency in Lahore combining presentations, guided intellectual conversations, and ethnographic research. The research focused on four shrines: Data Darbar, Bibi Pak Damen, Madhulal Hussein, and Mian Mir. These shrines tie together Iran and South Asia in myriad ways.

At some, the saints’ genealogies harken back to historical routes of travel resembling our own journey from Persia; at others it was the Shia or Sufi cultural practices, the rhythms of music, the steps of dance, or the architecture and poetic inscriptions that spoke to them.

Spending hours at the shrines, we trained our eyes, ears, and noses to perceive both similarities and differences to those back home. The beautiful structures and their Persian poetry were legible to us (while perhaps not to those around us). Meanwhile, the living culture in the courtyards, the sounds of qawwali or Punjabi rowza, the motions of dhamaal or the anointing of oil on the panjtan, and the mixed smell of ferni and hashish, were welcome and new.

We collaborated with Hast o Neest, a Lahore center for traditional arts, who graciously welcomed us into their space and hosted us for nights of qawwali, poetry, and calligraphy workshops.

The Lahore Biennale offered us an opportunity to take part in a conversation that was, for once, not dominated by the Western orientation of the global art and academic worlds. The constant pressure to explain and be relevant for a Western audience reduces so much work from the contemporary Middle East and South Asia to its exotic components.

The beauty of being in Lahore, bringing together Iranians and Pakistanis, was that we moved past the surface and explored concepts in depth at a level that can only happen when everyone in the room has a shared set of experiences and perspectives to bring to the table.

In a conversation about calligraphy, for example, we analyzed the detailed differences and their affective dimensions between Persian and Urdu nastaliq – a conversation that might not have gotten past oohing and aahing at the flowing “Arabic” script if it were occurring elsewhere.

When discussing shrines and art and music and embroidery, we found ourselves having far more rigorous conversations, true exchanges of information and opinions grounded in history and experience, rather than playing the role of native informants.

Instead of shouldering the burden of constantly explaining, we could delve into the real beauty and potential of contemporary art, where the feelings evoked and the research and history behind the artwork become important.

The Lahore Biennale provided a platform that was for us both unparalleled and unprecedented. Other Biennale events were also central to developing our experience.

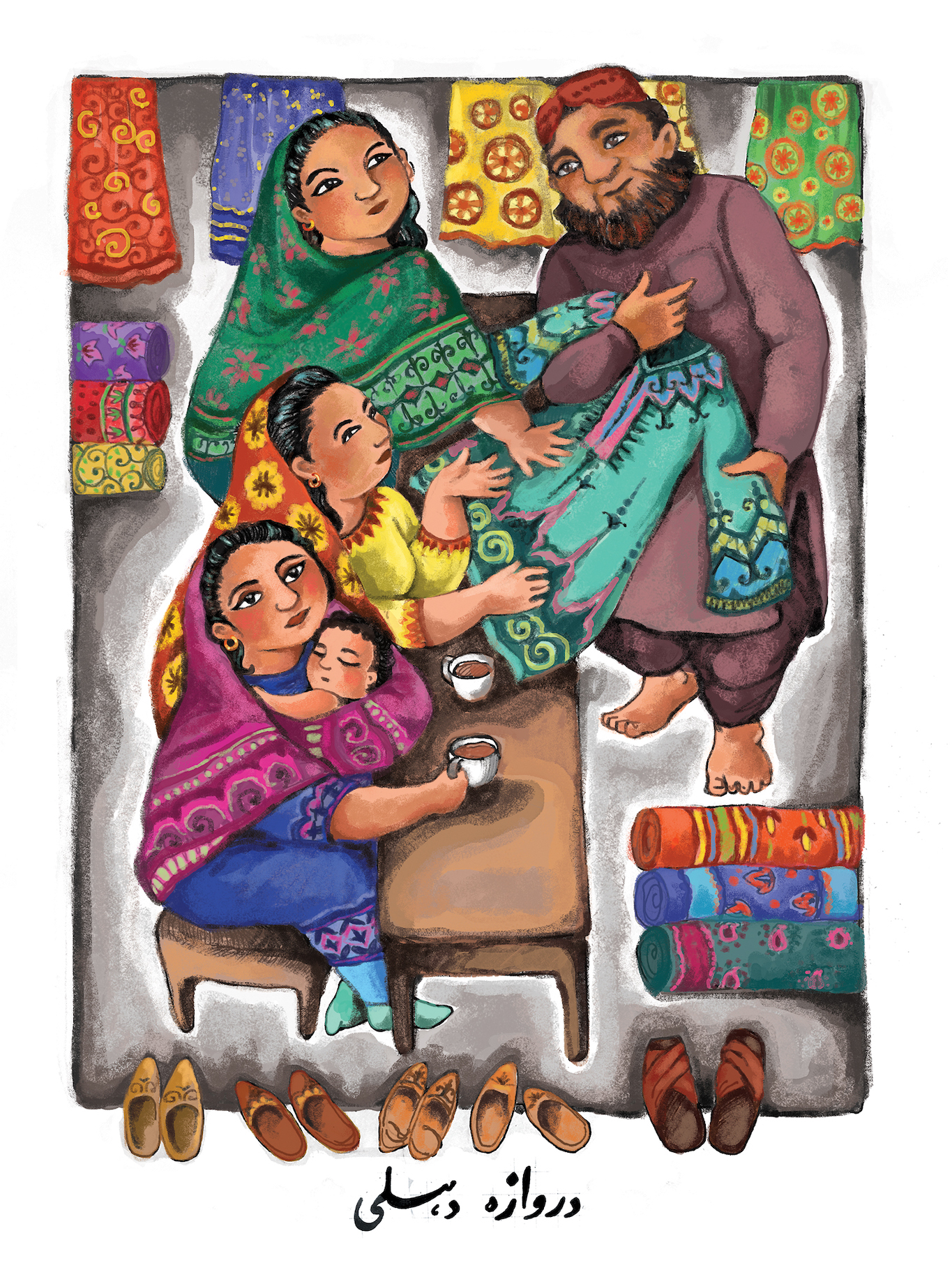

At the Biennale’s installations in the Lahore fort, we felt that art blended with everyday life. The experience of walking through the Old City, surrounded by thousands of nastaliq posters and lanes full of embroidery shops, became key to how we experienced the Biennale.

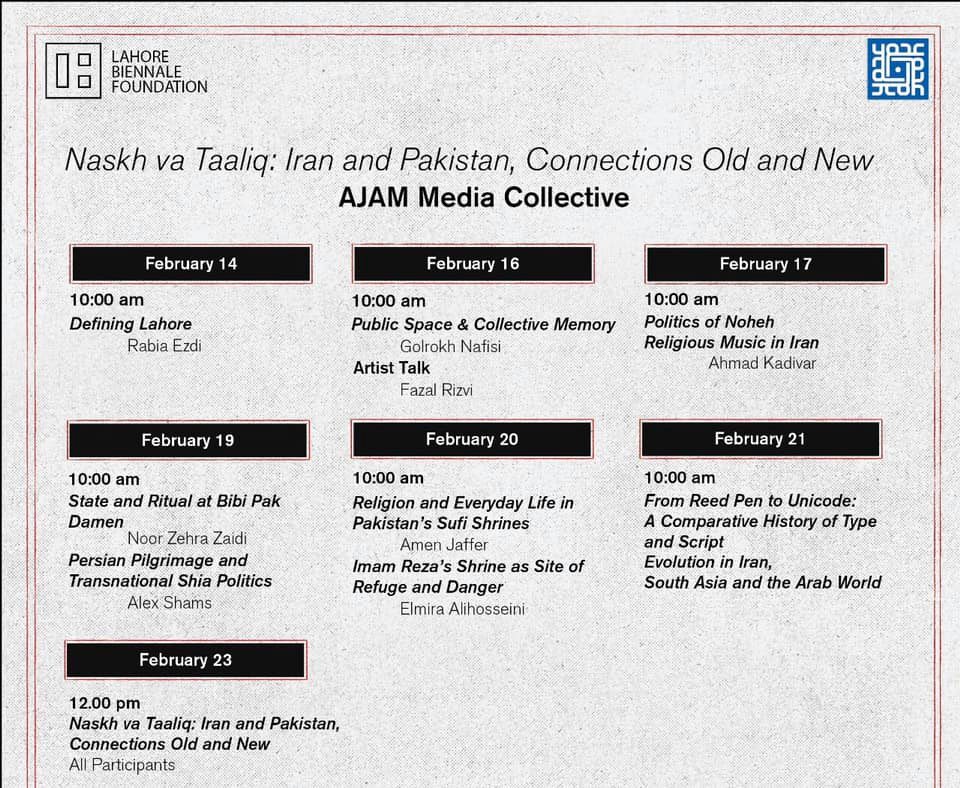

Participants in our workshop shared perspectives on art, culture, and history in a series of presentations and guided conversations, taking place at Hast o Neest and the Naqsh Art Center in the Old City.

The participation of diverse fields and backgrounds in the workshop – artists, anthropologists, graphic designers, urban sociologists, historians – was crucial in building the depth and breadth of the conversations we had.

Rabia Ezdi offered participants an introduction to the history of Lahore and its urban fabric, and artists Golrokh Nafisi and Fazal Rizvi presented about their art work and practices. Ahmad Kadivar spoke about the tradition of political and cultural resistance through noheh chanting in hussainiyah in Iran. Noor Zehra Zaidi discussed the push and pull between state and local forces at Bibi Pak Damen, Elmira Alihosseini discussed the history of shrines as sites of refuge as well as danger in the Shia tradition, and Amen Jaffer discussed the politics of everyday life at Pakistan’s Sufi shrines. I myself spoke on shrine pilgrimage and trade connections that once bound Iran and South Asia but came unravelled in the age of borders, nationalism, and colonialism in the 20th century. Sina Fakour discussed the comparative history of type and printing in Iran, South Asia, and the Arab World and Sohail Zuberi analyzed the role of calligraphy in Pakistani public space. Several participants also gave talks at the National College of Arts in Lahore.

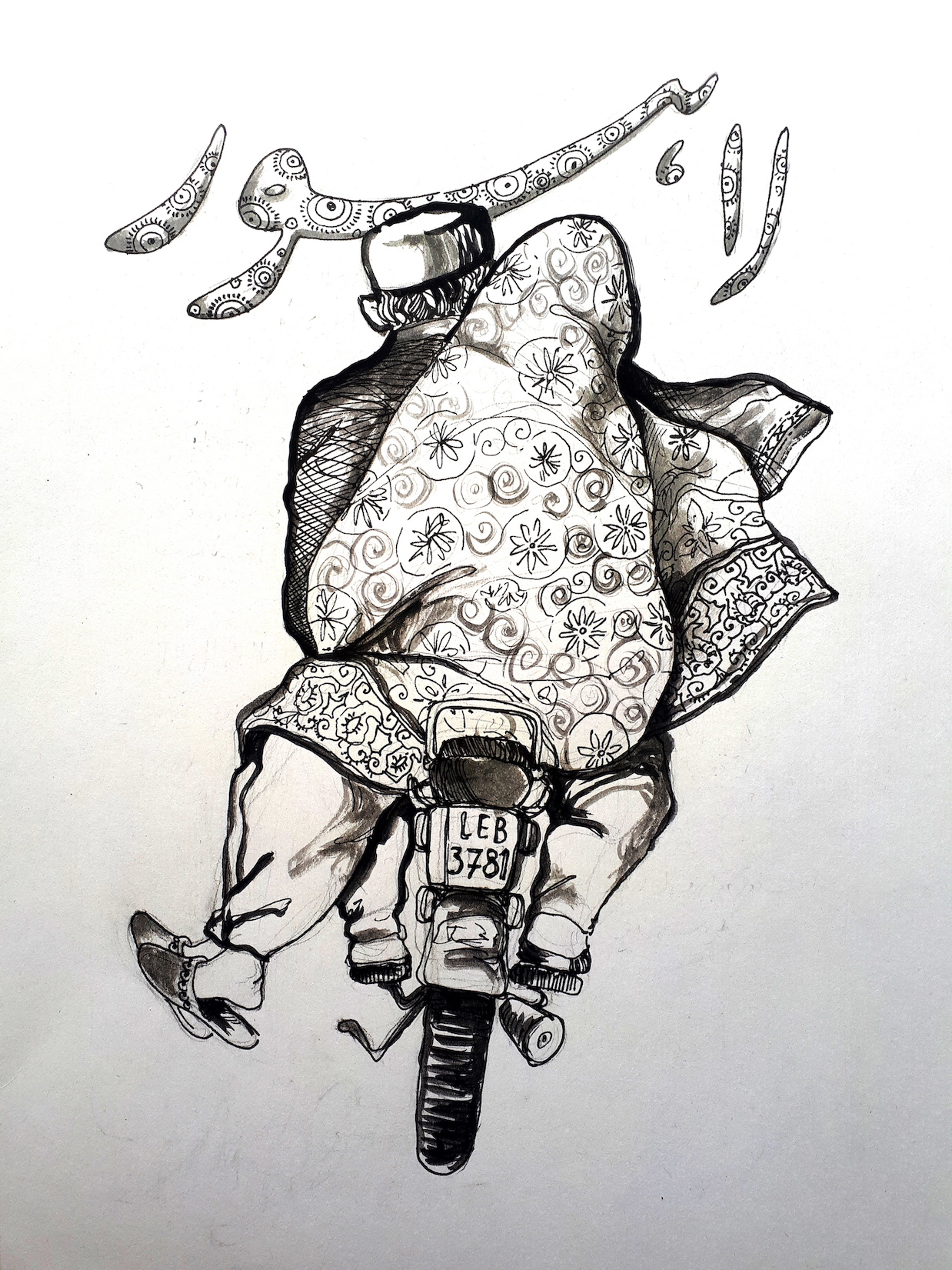

We commenced the workshop by offering a towfeh – a ceremonial gift – an embroidery created by Iranian artist Golrokh Nafisi that we unfurled inside the Naqsh Art School in Lahore’s Old City. The embroidery depicted the journey from Tehran to Lahore and all the stops along the way, showing where each sunrise and sunset would have us if we passed along the journey continuously.

In the process, it recreated an overland voyage that is today nearly impossible, one blocked by conflict, borders, and visa regimes which have built walls across a route that for millenia linked travelers between Lahore, Tehran, and the places in between. By unfurling this embroidery we highlighted how close our homes really were to each other – and how, despite the distance, it was possible to imagine that one day they may feel close again.

Standing at the shrines, reading Persian poetry inscribed on the walls, felt like a journey into a shared cultural past. In every interaction, we felt that our thirst in understanding our shared connections was met with an equal thirst by those around us.

One of the most beautiful moments was sitting in a cab barreling down Abbot Road, being serenaded by Iqbal’s verses by a driver who couldn’t believe his luck at finding a carload of Iranis – and who of course insisted we recite Iqbal’s verses for him as well.

Reflecting on our time at the Lahore Biennale, it is hard not to be overwhelmed by the mix of feelings we experienced – the closeness and the intimacy of a place that seemed at once completely unknown to us but was also immediately familiar. It is said in Persian poetry that you travel to find yourself, that through travel one becomes complete. Not only did Lahore become a part of us; through being in Lahore, it is as if we found a part of ourselves we didn’t even know existed.