Originally published in Journal Safar in September 2021 as part of Issue VI: Power.

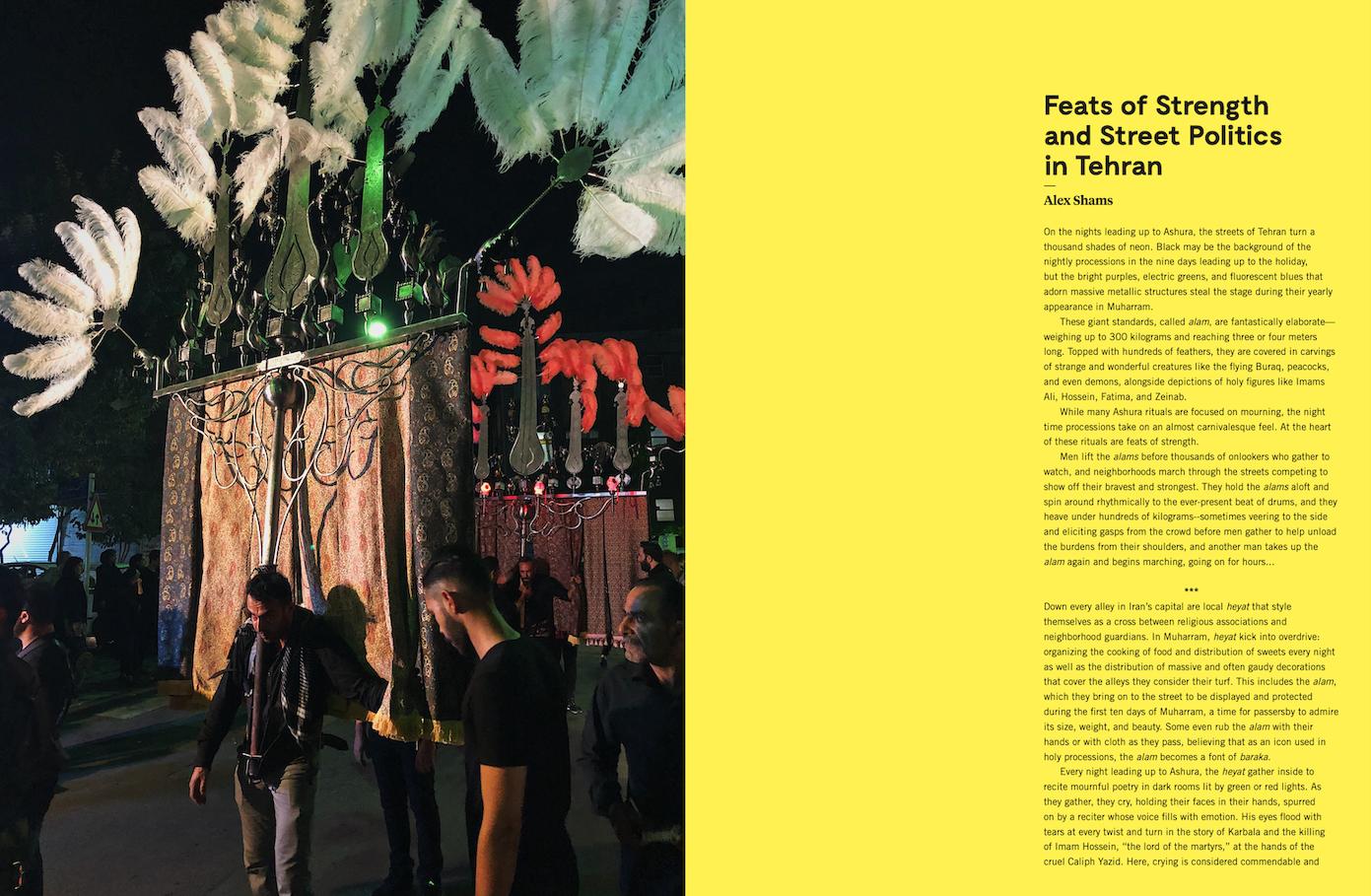

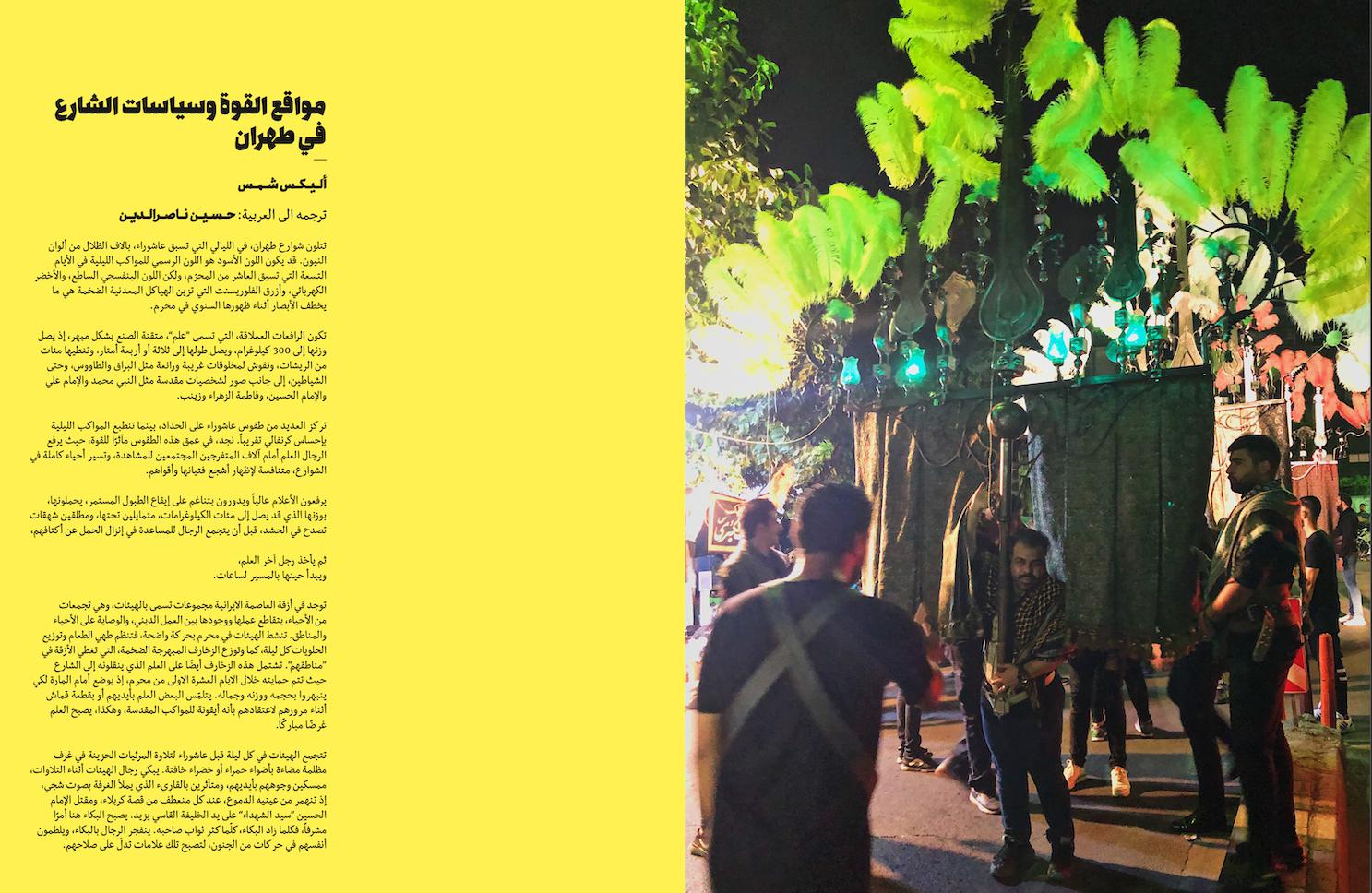

On the nights leading up to Ashura, the streets of Tehran turn a thousand shades of neon. Black may be the background of the nightly processions in the nine days leading up to the holiday, but the bright purples, electric greens, and fluorescent blues that adorn massive metallic structures steal the stage during their yearly appearance in Muharram.

These giant standards, called alam, are fantastically elaborate – weighing up to 300 kilograms and reaching three or four meters long. Topped with hundreds of feathers, they are covered in carvings of strange and wonderful creatures like the flying Buraq, peacocks, and even demons, alongside depictions of holy figures like Imams Ali, Hossein, Fatima, and Zeinab.

While many Ashura rituals are focused on mourning, the night time processions take on an almost carnivalesque feel. At the heart of these rituals are feats of strength.

Men lift the alams before thousands of onlookers who gather to watch, and neighborhoods march through the streets competing to show off their bravest and strongest. They hold the alams aloft and spin around rhythmically to the ever-present beat of drums, and they heave under hundreds of kilograms–sometimes veering to the side and eliciting gasps from the crowd before men gather to help unload the burdens from their shoulders, and another man takes up the alam again and begins marching, going on for hours…

Down every alley in Iran’s capital are local heyat that style themselves as a cross between religious associations and neighborhood guardians. In Muharram, heyat kick into overdrive: organizing the cooking of food and distribution of sweets every night as well as the distribution of massive and often gaudy decorations that cover the alleys they consider their turf. This includes the alam, which they bring on to the street to be displayed and protected during the first ten days of Muharram, a time for passersby to admire its size, weight, and beauty. Some even rub the alam with their hands or with cloth as they pass, believing that as an icon used in holy processions, the alam becomes a font of baraka.

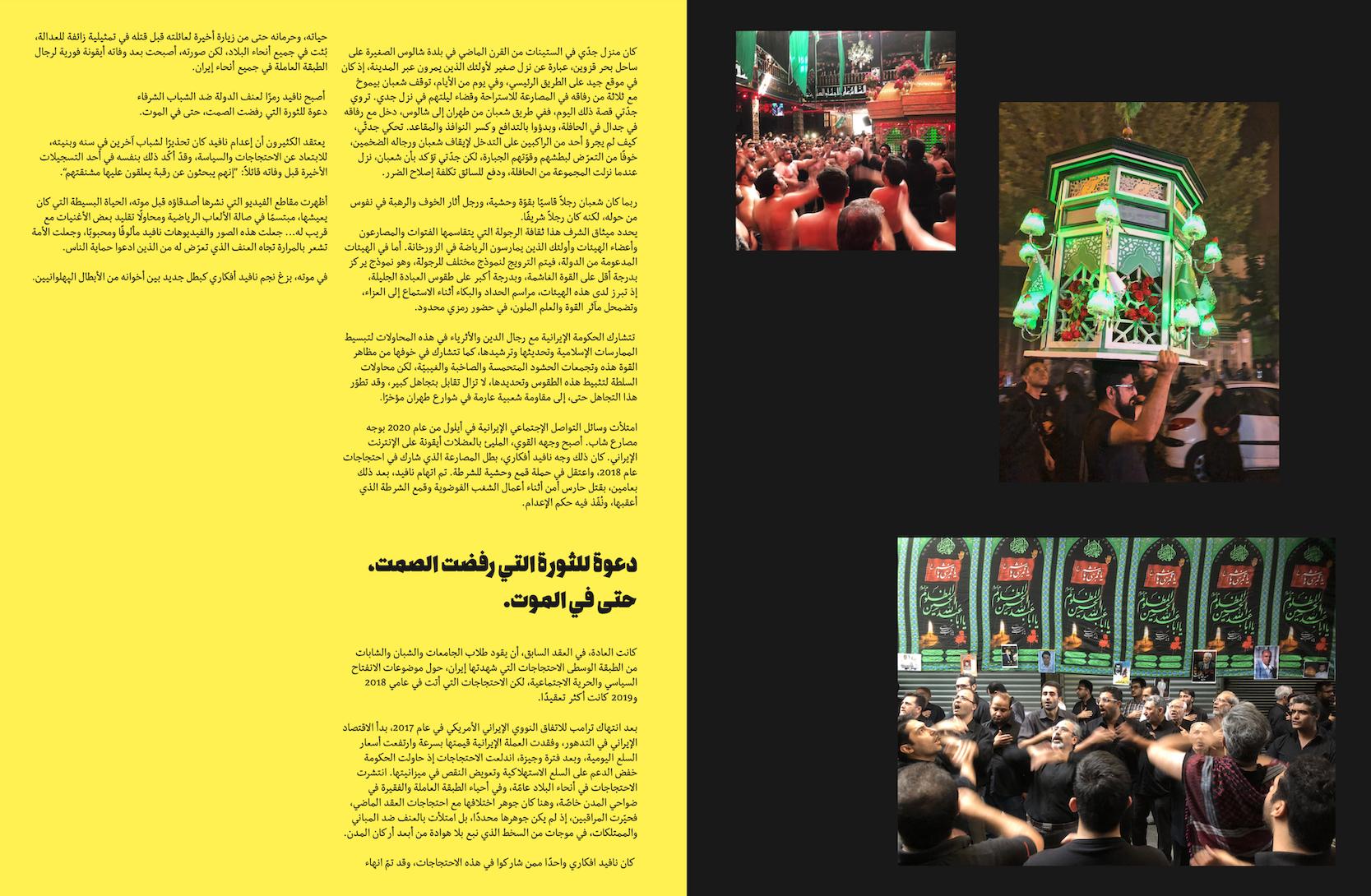

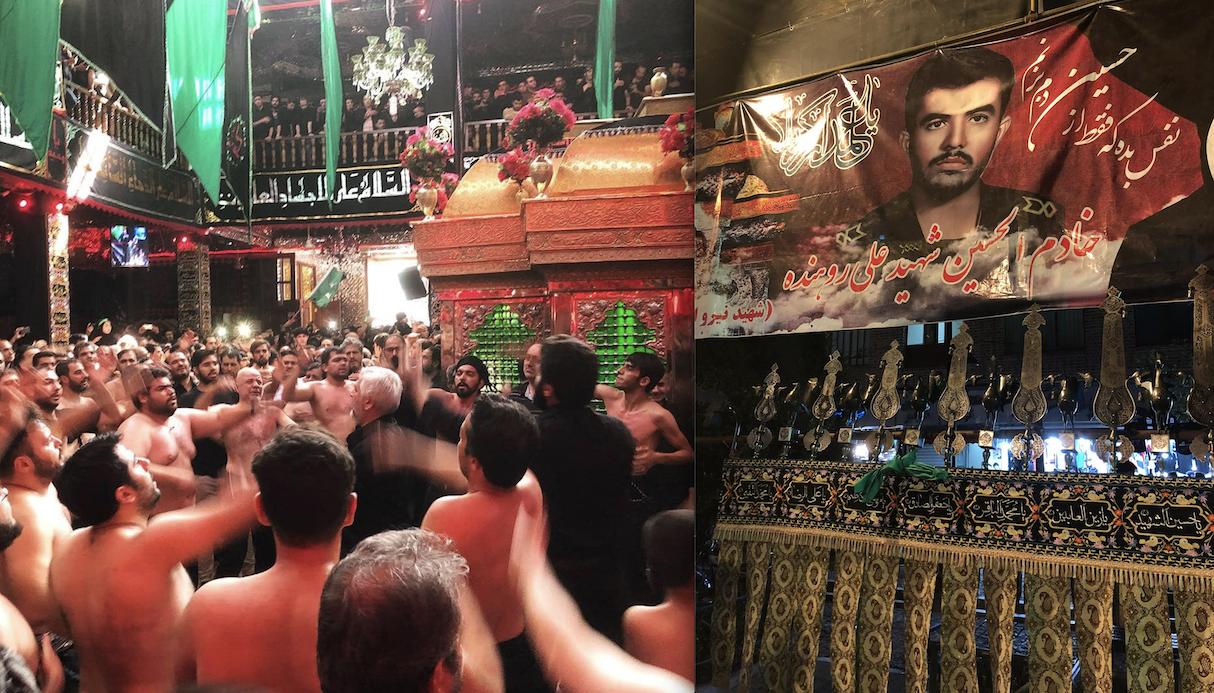

Every night leading up to Ashura, the heyat gather inside to recite mournful poetry in dark rooms lit by green or red lights. As they gather, they cry, holding their faces in their hands, spurred on by a reciter whose voice fills with emotion. His eyes flood with tears at every twist and turn in the story of Karbala and the killing of Imam Hossein, “the lord of the martyrs,” at the hands of the cruel Caliph Yazid. Here, crying is considered commendable and honorable. The more emotion a man shows, the greater he is. Bursting into tears uncontrollably, slapping oneself as if descending into madness… these are the signs of a good man.

As the storytelling of the battle reaches a crescendo, and the killing of holy figures is recounted one by one, the men assembled break into moans. Once the worst has passed, the lights are dimmed further, the shirts come off, and recitation of a different kind of poetry begins: everyone stands up, groups gather into tight circles, and boisterous, competitive chanting takes over, accompanied by the beat of rhythmic chest-beating.

The chanting is just the beginning. As the heyat band begins banging against huge Yamaha drums to the beat of saxophones, the heyat heads outside to begin lifting the alam, and the neighborhood floods into the street to get a good view of the strongest men wrapping huge harnesses around their bodies to lift up the alam. They crowd the streets late into the night, as processions commence around 10 pm and continue on hours after midnight.

The alam are so heavy that within seconds of placing them on their shoulders, massive blisters begin to form atop their curved backs. Walking through the alleyways, they reach main streets where other heyat proceed with their own alams. As heyats encounter each other, they bow their alams in greeting, even as they compete to show off how well they hold them up. Dozens of men from their heyat stand close by, ready to intervene if the alam-bearer should collapse, checking his sweat and stamina at every step of the way. This is especially key right before the hand-off from one bearer to another; often, a bearer will take the alam at the last moment and begin spinning, flipping around with hundreds of kilograms of metal and fluorescent flowers above, like a peacock showing off its feathers, a move met with gasps, excitement, and sensual energy from the gathered crowds. They stare mesmerized at these men whose strength lifts mountains and whose eyelashes stir hearts.

This scene is repeated in neighborhoods across Tehran, night after night—a yearly performance unlike any other. Although women crowd the street as onlookers (and have their own private ceremonies), the processions are a strictly male affair. These rituals uphold the heyat’s power and presence in public space and solidify their role as protectors of the neighborhood. They also valorize a particular kind of masculinity, one that is both physically strong, as demonstrated by the feats of strength, but also gentle and pious, as in the collective mourning ceremonies that precede it.

In times of uncertainty, heyat associations have often become something akin to neighborhood toughs. During military rule in 1978-9, for example, they became key parts of local organization to resist the Shah’s rule. After the Revolution, attempts were made to co-opt these networks into the state, but the result was the creation of parallel and competing heyat – those that followed a pro-state line and those that remained independent.

Beneath the heyat and their activities lie a paradigm of masculinity with roots in chivalrous culture – called futuwwa or javanmardi in Persian – a model of how a proper, strong, and pious man should look and should orient himself toward the world. The heyat is a brotherhood and a religious association, united in Muharram by devotion to Imam Hossein and his father, Imam Ali, both of whom represent paradigmatic models of masculinity. Imam Ali is a kind leader and father, and Imam Hussein is a young man who stands up to authority in the name of what he considers truth. In Muharram rituals, men’s love for Imam Hussein is paramount, and by crying at the mourning ceremonies, lifting up the massive alam, and serving their community through distribution of food, members of the heyat perform their ideal masculine selves.

But this performance is not always successful – the processions sometimes devolve into turf wars, break out into street fights, or become overtaken by raucous flirting. But this is part of the appeal – unlike the mass political rituals of post-Revolutionary Iran, which are closely stage-managed to exude an aura of absolute control and organization, the nights of Muharram are an uncontrolled, unpredictable affair where anything can happen.

The feats of strength in Muharram are one manifestation of a wider complex of masculinity-focused rituals that once pervaded many aspects of Iranian public culture, traces of which can still be seen today.

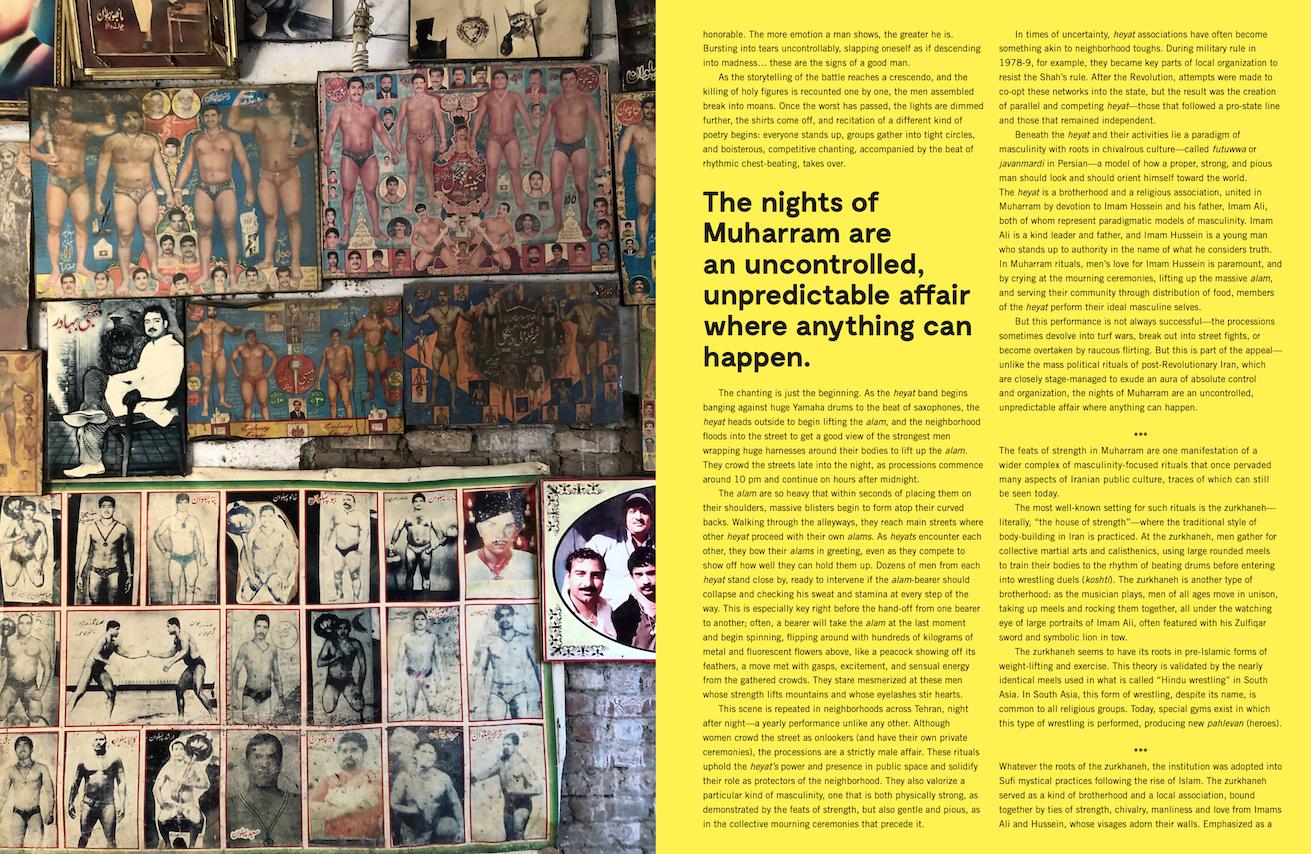

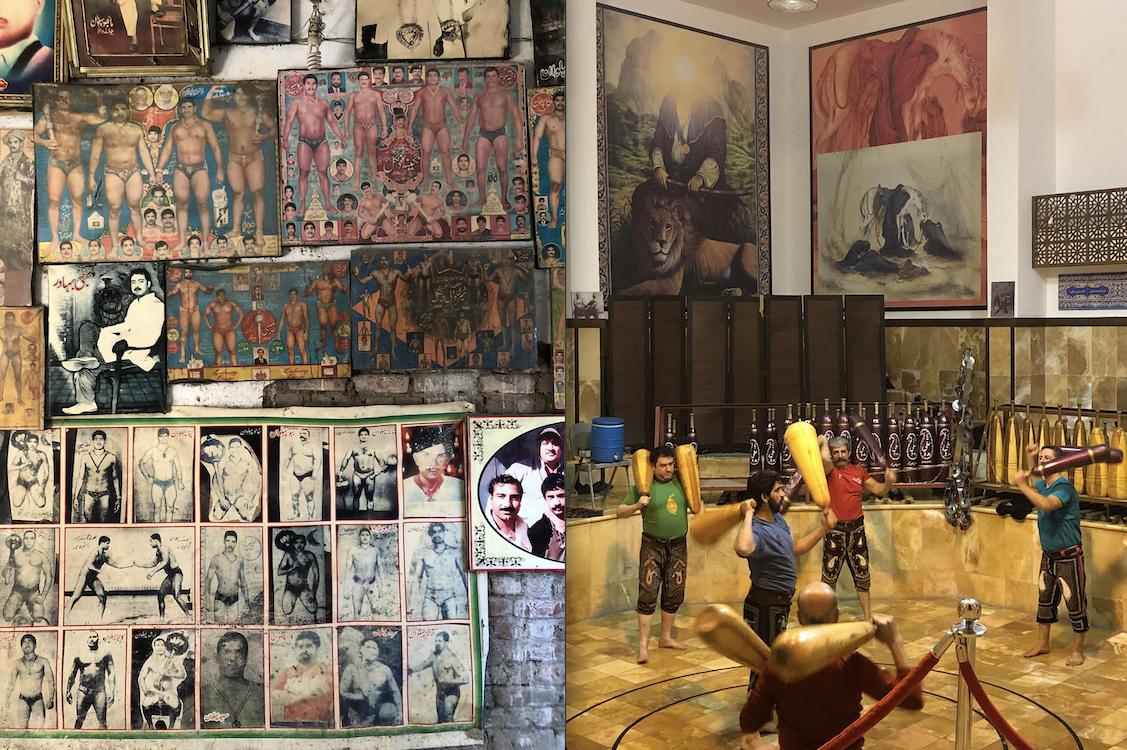

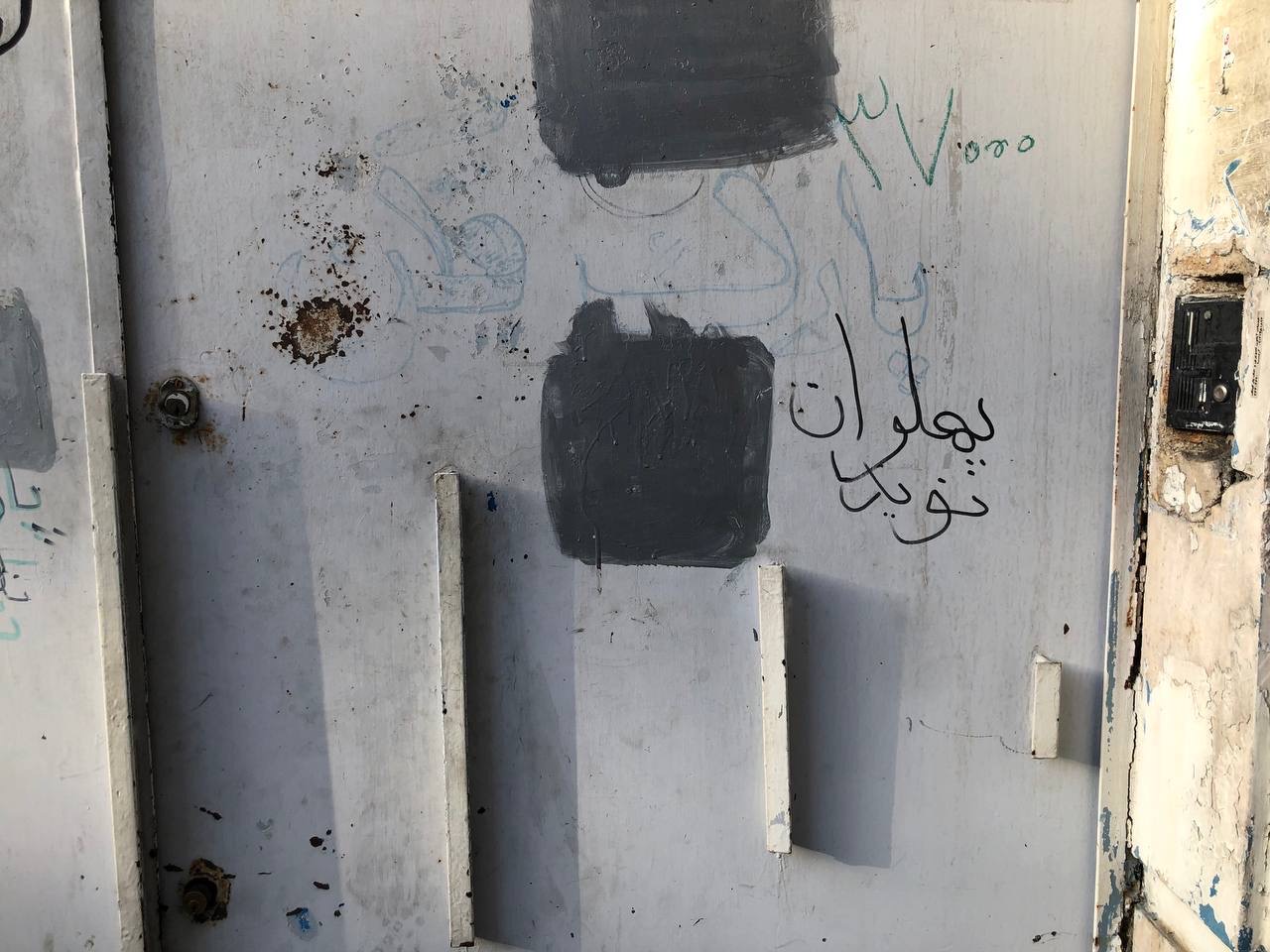

The most well-known setting for such rituals is the zurkhaneh – literally, “the house of strength” – where the traditional style of body-building in Iran is practiced. At the zurkhaneh, men gather for collective martial arts and calisthenics, using large rounded meels to train their bodies to the rhythm of beating drums before entering into wrestling duels (koshti). The zurkhaneh is another type of brotherhood: as the musician plays, men of all ages move in unison, taking up meels and rocking them together, all under the watching eye of large portraits of Imam Ali, often featured with his Zulfiqar sword and symbolic lion in tow.

The zurkhaneh seems to have its roots in pre-Islamic forms of weight-lifting and exercise. This theory is validated by the nearly identical meels used in what is called “Hindu wrestling” in South Asia. In South Asia, this form of wrestling, despite its name, is common to all religious groups. Today, special gyms exist in which this type of wrestling is performed, producing new pahlevan (heroes).

Whatever the roots of the zurkhaneh, the institution was adopted into Sufi mystical practices following the rise of Islam. The zurkhaneh served as a kind of brotherhood and a local association, bound together by ties of strength, chivalry, manliness and love from Imams Ali and Hussein, whose visages adorn their walls. Emphasized as a way to promote a sound body and mind in sync with each other, the zurkhaneh became a place of camaraderie, love, and connection.

The heyat religious associations active in modern Iran also find their roots in Sufi brotherhoods. In the 1500s, the Safavids converted Iran from Sunnism to a Shi’ism, but beneath that seeming conversion lay the reality of heavy Sufi influence on Iranian religious practices. Mystical tendencies in Iranian Sunni Islam ultimately came to define the Shi’ism of popular Islam after the conversion. While the ulema may have gone to great lengths to break down Sufi power and influence in Iranian society, Sufi practices and beliefs were integrated at every level and largely immovable.

This can still be seen today in the terminology used: for example, tekiyeh, which historically referred to a Sufi lodge, is used in Iran to describe large buildings where ceremonial re-enactments of the battle of Karbala are performed and where heyat are based. Additionally, the widespread use of shamayel, sacred images of the Imams as well as the Prophet Muhammad, is another feature common to both Sufism and popular Iranian Shi’ism. These shamayel often adorn the alam themselves, which are considered by some as holy icons bursting with baraka, or blessings, because they are used in processions mourning Imam Hossein every year.

While the Muharram processions are often seen through the lens of the religious story, they are social occasions as well – friends show off, trade barbs, aid one another as they begin to falter under the weight of alam, and flirt as they impress passerby. Indeed these rituals have always been boisterous and loud. They have often been looked down upon by religious clerics and wealthy Iranians and dismissed as representations of the Islam of laat-o-loot, of street ruffians. But the same figures condemned as violent by some are adored by others, like Shaaban Jaafari – known as Shaaban Bimokh, literally “Shaaban the Brainless” – a famous wrestler and gangster from the 1950s who played a key role in the 1953 coup d’etat that brought the Shah back to power with CIA help.

In the 1960s, my grandparents’ home in the small town of Chalus on the Caspian coast served as a small inn for those who passed through the town, for it was well-located on the main road. On one occasion, Shaaban Bimokh stopped in for the night with three of his huge wrestling companions. As my grandmother tells the story, on Shaaban’s way from Tehran to Chalus, the group got into an argument on the bus and started pushing and shoving, breaking windows and destroying seats. No one dared intervene to stop the huge men, fearing that they might wield their enormous strength against other passengers. But when the group got off the bus, Shaaban stepped down onto the road and paid the conductor the cost of repairing the damage. Shaaban may have been a brutish tough guy with more strength than he knew what to do with it – a man whose sheer bulk inspired fear and awe in those around him – but he was also an honorable man. This code of honor defines the culture of manliness shared by laats (toughs), wrestlers, members of the heyat, and those who exercise at the zurkhaneh.

At the state-supported heyats, a different model of masculinity is promoted: one that focuses less on brute strength and more on solemn worship. The mourning ceremonies and crying while listening to poetry are the key commemorations while the feats of strength and colorful alam have only a limited, symbolic presence. These attempts to streamline, modernize, and rationalize Islamic practice unite Iran’s government with the well-to-do who find these displays of strength and gatherings of excited crowds scary, raucous, and superstitious. Still, attempts to discourage these rituals have been largely ignored, and sometimes, they have provoked a will to power on the streets of Tehran that has developed into all-out resistance.

In September 2020, the face of a wrestler lit up social media across Iran. His stern, muscular visage became ubiquitous on the Iranian internet. Navid Afkari was a champion wrestler who took part in protests in 2018. He was arrested in a brutal police crackdown. Two years later, he was accused of murdering a security guard – ostensibly during the chaotic riots and police crackdown that had followed them – and executed.

The most visible protests Iran had witnessed in the decade before 2018 had been led by university students and the middle classes on themes of political openness and social freedom. After Trump’s violation of the Iran-US nuclear deal in 2017, Iran’s economy began to tank, with the Iranian currency, the rial, quickly losing value and the price of everyday goods soaring. Not long after, protests broke out as the government tried to lower subsidies on consumer goods and make up for its own budgeting shortfall. Amid these events, protests broke out across the country, flaring up in working-class and impoverished districts on the urban outskirts. To those who had followed earlier protests, the 2018 and 2019 protests were bewildering. The core of the protests was hard to locate; protests were full of violence against buildings and property – a seemingly inexorable wave of discontent emanating from the cities’ furthest corners. Afkari participated in one of these waves.

In a travesty of justice closely watched across the country, his life was taken. He was denied even a final visit from his family.

But in death, his image became an instant rallying cry for working-class men across Iran. It became a symbol of state violence against noble young men – a call to revolt that refused to be silent, even in death. Many thought that Afkari was executed as a warning to other young men of his age and physical build to stay far away from protests and politics. In one of the last recordings before his death, Afkari suggested he felt so as well, saying: “They are looking for a neck to hang their rope.” After he was killed, endearing videos posted by his friends showed him living an ordinary life: lip syncing with his cousin, smiling at the gym… These photos and videos made Navid Afkari familiar, beloved, and this ultimately left the nation bitter towards the violence of those who claimed to protect the people.

In death, Navid Afkari has become a new hero from among the pahlevans.

تتلون شوارع طهران، في الليالي التي تسبق عاشوراء، بالاف الظلال من ألوان النيون. قد يكون اللون الأسود هو اللون الرسمي للمواكب الليلية في الأيام التسعة التي تسبق العاشر من المحرّم، ولكن اللون البنفسجي الساطع، والأخضر الكهربائي، وأزرق الفلوريسنت التي تزين الهياكل المعدنية الضخمة هي ما يخطف الأبصار أثناء ظهورها السنوي في محرم.

تكون الرافعات العملاقة، التي تسمى “علم”، متقنة الصنع بشكل مبهر، إذ يصل وزنها إلى ٣٠٠ كيلوغرام، ويصل طولها إلى ثلاثة أو أربعة أمتار، وتغطيها مئات من الريشات، ونقوش لمخلوقات غريبة ورائعة مثل البراق والطاووس، وحتى الشياطين، إلى جانب صور لشخصيات مقدسة مثل النبي محمد والإمام علي والإمام الحسين، وفاطمة الزهراء وزينب.

تركز العديد من طقوس عاشوراء على الحداد، بينما تنطبع المواكب الليلية بإحساس كرنفالي تقريباً. نجد، في عمق هذه الطقوس ماَثرًا للقوة، حيث يرفع الرجال العلم أمام آلاف المتفرجين المجتمعين للمشاهدة، وتسير أحياء كاملة في الشوارع، متنافسة لإظهار أشجع فتيانها وأقواهم.

يرفعون الأعلام عالياً ويدورون بتناغم على إيقاع الطبول المستمر، يحملونها، بوزنها الذي قد يصل إلى مئات الكيلوغرامات، متمايلين تحتها، ومطلقين شهقات تصدح في الحشد، قبل أن يتجمع الرجال للمساعدة في إنزال الحمل عن أكتافهم، ثم يأخذ رجل اَخر العلم، ويبدأ حينها بالمسير لساعات.

توجد في أزقة العاصمة الايرانية مجموعات تسمى بالهيئات، وهي تجمعات من الأحياء، يتقاطع عملها ووجودها بين العمل الديني، والوصاية على الأحياء والمناطق. تنشط الهيئات في محرم بحركة واضحة، فتنظم طهي الطعام وتوزيع الحلويات كل ليلة، كما وتوزع الزخارف المبهرجة الضخمة، التي تغطي الأزقة في “مناطقهم”.

تشتمل هذه الزخارف أيضًا على العلم الذي ينقلونه إلى الشارع حيث تتم حمايته خلال الايام العشرة الاولى من محرم، إذ يوضع أمام المارة لكي ينبهروا بحجمه ووزنه وجماله. يتلمّس البعض العلم بأيديهم أو بقطعة قماش أثناء مرورهم لاعتقادهم بأنه أيقونة للمواكب المقدسة، وهكذا، يصبح العلم غرضًا مباركًا.

تتجمع الهيئات في كل ليلة قبل عاشوراء لتلاوة المرثيات الحزينة في غرف مظلمة مضاءة بأضواء حمراء أو خضراء خافتة. يبكي رجال الهيئات أثناء التلاوات، ممسكين وجوههم بأيديهم، ومتأثرين بالقارىء الذي يملأ الغرفة بصوت شجي، إذ تنهمر من عينيه الدموع، عند كل منعطف من قصة كربلاء، ومقتل الإمام الحسين “سيد الشهداء” على يد الخليفة القاسي يزيد. يصبح البكاء هنا أمرًا مشرفاً، فكلما زاد البكاء، كلّما كثر ثواب صاحبه. ينفجر الرجال بالبكاء، ويلطمون أنفسهم في حركات من الجنون، لتصبح تلك علامات تدلّ على صلاحهم.

يروي القارئ مقتل الشخصيات المقدسة واحداً تلو الاخر، ومع وصول قصة المعركة إلى ذروتها، ينفجر الرجال أنيناً وبكاءً وبعد أن ينتهي الجزء الأصعب من القصة، يتم تعتيم الأضواء أكثر، وتُنزع القمصان، ثم يبدأ القارئ بتلاوة نوع اَخر من النوح.

يقف الجميع، في دوائر ضيقة، مرددين صيحات بصخب تنافسي، يصحبه إقاع اللطم على الصدر، ثم يتصاعد النسق لتبدأ فرق الهيئات بالقرع على طبول ياماها الضخمة على إيقاع الساكسوفون، متجهة إلى الخارج لتبدأ في رفع العلم، فيما تتدفق أحياء المنطقة إلى الشارع لرؤية أفضل وأقوى الرجال الذين يلفون الاحزمة الضخمة حول أجسادهم من أجل رفع العلم. يتزاحم الحشد في الشوارع حتى وقت متأخر من الليل، إذ تبدأ المواكب في حوالي العاشرة مساءً، وتستمر حتى ساعات بعد منتصف الليل.

تبدأ القروح الضخمة بالتشكل فوق ظهور حاملي العلم المنحنية، بعد ثوانٍ قليلة فقط من وضعه فوق أكتافهم، فالعلم ثقيل جداً. يمشون في الازقة، ويصلون إلى الشوارع الرئيسية بينما يمضي آخرون إلى أزقّتهم الخاصة. تلتقي الهيئات المختلفة مع بعضها، فينحنون للتحية، وهم يتنافسون للتباهي بقدرتهم على التحمل. يقف العشرات من الرجال الهيئات على مقربة من العلم، مستعدين للتدخل في حال انهار حامله أو ضعفت قوته، ومراقبين طاقته وقدرته على التحمل في كل خطوة من الطريق. لتسليم العلم طقوس خاصة، إذ يأخذ حامل العلم في اللحظة الاخيرة بالدوران، وهو يتقلب حاملًا مئات الكيلوجرامات من المعدن والزهور الساطعة، كطاووس يتبختر بريشه، ثم تُقابل حركته بلهاث ودهشة وإثارة من الحشود المجتمعة. يحدق الناس فيه، رجلٌ، في كفيه ما قد يحرّك الجبال، وفي رمشيه ما يحرّك القلوب.

يتكرر هذا المشهد في جميع أنحاء طهران ليلة بعد ليلة كأداء سنوي لا مثيل له، كما تحتشد النساء في الشارع ويتفرجن، أو قد يقمن احتفالات خاصة بهن، إلا أن المواكب شأن خاص بالرجال. تدعم قوة الهيئات ووجودها في الأماكن العامة هذه الطقوس، إذ ترسخ دورها كمجموعات حامية للأحياء، ونجد هنا دور للذكورة، والقوة الجسدية ومآثرها، إنما مع لطف و تقوى، كما هو الحال في مراسم الحداد الجماعية التي تسبقها.

في أوقات عدم الاستقرار، يكبر دور الهيئات كقوى تمثل الأحياء، فقد كانت الهيئات مثلًا، جزءًا رئيسيًا في التنظيم المقاوم لحكم الشاه في فترة الحكم العسكري بين ١٩٧٨ و١٩٧٩، وقد حصلت محاولات لاستمالة هذه الشبكات في الدولة بعد الثورة، ولكن النتيجة كانت إنشاء هيئات موازية اتبع بعضها الدولة، وظل بعضها الآخر مستقلًا.

يتفرع عن الهيئات وأنشطتها، نموذج للرجولة، متجذر في ثقافة الشجاعة، وهو نموذج الفتوة، أو ” جوان مردی” باللغة الفارسية. يطرح هذا نموذج لكيفية رؤية الرجل السليم والقوي والتقيّ، وكيفية مواجهته للعالم. تتحد الهيئات في محرم للاخلاص للامام الحسين ووالده الامام علي، إذ يعبّر كلّ منهما عن نموذج مثالي للذكورة، فترى الهيئات في الإمام علي القائد والأب طيب، وفي الإمام الحسين الشاب الذي يقف في وجه السلطة باسم الحقيقة. يصبح حب الرجال وإخلاصهم للإمام الحسين في طقوس محرم أمراً مهماً، أذ يتمم أعضاء الهيئات دورهم كذكور من خلال البكاء في مراسم الحداد، ورفع العلم الضخم، وخدمة مجتمعاتهم وتوزيع الطعام، لكنّ هذا الاداء لا ينجح دومًا، إذ تتحول المواكب أحياناً إلى حروب على النفوذ، تندلع معاركها في الشوارع، وتغلب عليها المصاخبات والمشاحنات القوية، وعلى عكس الطقوس الجماهيرية لإيران ما بعد الثورة، والتي يتم إدارتها عن كثب لتوضيح مكانة السيطرة المنظمة المطلقة للسلطة، فإن ليالي محرم لا تخضع لهذه السيطرة، ويصعب التنبؤ بما يحدث أو ما يمكن أن يحدث فيها.

تعتبر مظاهر القوة في محرم واحدة من مجموعة أوسع من الطقوس الرجولية التي سادت في الماضي في العديد من جوانب الثقافة العامة الايرانية، والتي لا تزال واضحة الآثار حتى يومنا الحالي، وتبرز ” الزورخانة ” وتعني بيت القوة بالفارسية، كأحد الأماكن الاكثر شهرة لهذه الطقوس، وهو نادٍ تمارس فيه الأشكال التقليدية لبناء قوى الأجسام في إيران. يجتمع الرجال في الزورخانة لتعلم الدفاع عن النفس الجماعي، و تمارين الجسد، باستخدام الأدوات الخشبية الكبيرة المدورة لتدريب العضلات، بالتزامن مع إيقاع الطبول الذي يسبق الدخول في مباريات المصارعة (الكوش). تتشكّل في الزورخانة أنواع من الاخوّة، إذ تُعزف الموسيقى، ويحلّ انسجامٌ بين رجالٍ مِن جميع الاعمار، يحركون الادوات الخشبية بتناغم معاً، تحت صور كبيرة للامام علي، غالباً ما يكون فيها بصحبة سيفه ذو الفقار، وأسد رمزي. للزورخانة، على ما يبدو، جذور في طقوس ما قبل الإسلام لرفع الاثقال والتمارين الرياضية، إذ يُلاحظ تشابه الأدوات الخشبية ومطابقتها تقريباً لتلك المستخدمة في المصارعة الهندوسية في جنوب اَسيا، وعلى الرغم من اسم هذه المصارعة المرتبط بالديانة الهندوسية، إلا أنها شائعة لدى جميع الجماعات الدينية في جنوب آسيا. أما هنا، فتوجد صالات رياضية خاصة يتم فيها أداء هذا النوع من المصارعة، وتدريب أبطال جدد، يسمّون بالفارسية بإسم “پهلوان” (أي البطل القوي) .

تمّ تبني الزورخانة، أياً تكن جذورها، في الممارسات الصوفية بعد ظهور الإسلام، إذ شكّلت أنواعًا من الاخوة والجمعيات المحلية، تجمعها روابط من القوة والفروسية والرجولة والحب للإمام علي والإمام الحسين، ووجهيهما المزيّنان لجدران الزورخانات، التي اعتبرت مكانًا لتقوية الجسم والعقل مع بعضهما، وصارت مكانًا للتجمع والحب والتواصل.

تجد الجمعيات الدينية الحديثة في إيران اليوم جذورها أيضًا في الاخويات الصوفية. ففي القرن السادس عشر، حول الصفويون ايران من المذهب السني إلى المذهب الشيعي، وظهر في ثنايا هذا التحوّل، التأثر الصوفي القويّ على الممارسات الدينية الايرانية، إذ تسرّبت الميول الصوفية الغيبية في الاسلام السني الايراني إلى شيعية الاسلام الشعبي بعد التحول، وعلى الرغم من محاولات العلماء والمراجع الحثيثة لتحطيم القوة الصوفية وتأثيرها في المجتمع الايراني، نجحت الممارسات الصوفية في الإندماج في المعتقدات على جميع مستويات المجتمع، ولا يزل يمكننا رؤية هذا الإندماج في مصطلحاتنا اليوم، مثل مصطلح التكية، وهي كلمة استخدمت سابقًا للدلالة على المحافل الصوفية، وتستخدم اليوم في إيران لوصف المباني الكبيرة حيث تتم تمثيل احتفالية معركة كربلاء وحيث تتمركز الهيئات، ومصطلح الـ” شمايل”، وهي الصور المقدسة للائمة والنبي محمد اللتي تنتشر بكثرة، وهي سمة مشتركة أيضاً بين الصوفية والشيعية الايرانية الشعبية. غالبًا ما تزين هذه الشمائل العلم، ويعتبرها البعض أيقونات تنفجر بالبركة، إذ تستخدم في مواكب حداد الامام الحسين كل عام، ولزاماً، فإن مواكب محرم التي غالباً ما تروى عبر القصة الدينية، هي مناسبات اجتماعية أيضاً، يتباهى فيها الأصدقاء ويتبادلون المزاح والهجاء، ويساعدون بعضهم في تجنب العثرات تحت وطأة العلم، ويتغازلون سويًا مع المارة والمعجبين.

كانت هذه الطقوس صاخبة دائماً، وغالباً ما نظر إليها رجال الدين والأثرياء من الإيرانيين بازدراء ورفض، باعتبارها تمثيلات لإسلام أشرار الشوارع وزعرانها. يرفض الكثيرون هذه الشخصيات لعنفها وصخبها، لكنّ بضعها يُعشق ويُمجّد من الآلاف، شخصيات مثل شعبان الجعفري المعروف باسم “شعبان بيموخ” أي “شعبان بلا عقل”، وهو مصارع ورجل عصابات شهير من الخمسينيات، لعب دوراً أساسياً في انقلاب عام ١٩٥٣ الذي أعاد الشاه إلى السلطة بمساعدة وكالة الاستخبارات المركزية الاميركية.

كان منزل جدّي في الستينات من القرن الماضي في بلدة شالوس الصغيرة على ساحل بحر قزوين، عبارة عن نزل صغير لأولئك الذين يمرون عبر المدينة، إذ كان في موقع جيد على الطريق الرئيسي، وفي يوم من الأيام، توقف شعبان بيموخ مع ثلاثة من رفاقه في المصارعة للاستراحة وقضاء ليلتهم في نزل جدي. تروي جدّتي قصة ذلك اليوم، ففي طريق شعبان من طهران إلى شالوس، دخل مع رفاقه في جدال في الحافلة، وبدؤوا بالتدافع وكسر النوافذ والمقاعد. تحكي جدتّي، كيف لم يجرؤ أحد من الراكبين على التدخل لإيقاف شعبان ورجاله الضخمين، خوفًا من التعرّض لبطشهم وقوّتهم الجبارة، لكن جدّتي تؤكد بأن شعبان، نزل عندما نزلت المجموعة من الحافلة، ودفع للسائق تكلفة إصلاح الضرر.

ربما كان شعبان رجلاً قاسيًا بقوّة وحشية، ورجل أثار الخوف والرهبة في نفوس من حوله، لكنه كان رجلاً شريفًا.

يحدد ميثاق الشرف هذا ثقافة الرجولة التي يتقاسمها الفتوات والمصارعون وأعضاء الهيئات وأولئك الذين يمارسون الرياضة في الزورخانة. أما في الهيئات المدعومة من الدولة، فيتم الترويج لنموذج مختلف للرجولة، وهو نموذج يركز بدرجة أقل على القوة الغاشمة، وبدرجة أكبر على طقوس العبادة الجليلة، إذ تبرز لدى هذه الهيئات، مراسم الحداد والبكاء أثناء الاستماع إلى العزاء، وتضمحل مآثر القوة والعلم الملون، في حضور رمزي محدود.

تتشارك الحكومة الإيرانية مع رجال الدين والأثرياء في هذه المحاولات لتبسيط الممارسات الإسلامية وتحديثها وترشيدها، كما تتشارك في خوفها من مظاهر القوة هذه وتجمعات الحشود المتحمسة والصاخبة والغيبيّة، لكن محاولات السلطة لتثبيط هذه الطقوس وتحديدها، لا تزال تقابل بتجاهل كبير، وقد تطوّر هذا التجاهل حتى، إلى مقاومة شعبية عارمة في شوارع طهران مؤخرًا.

امتلأت وسائل التواصل الإجتماعي الإيرانية في أيلول من عام ٢٠٢٠ بوجه مصارع شاب. أصبح وجهه القوي، المليئ بالعضلات أيقونة على الإنترنت الإيراني. كان ذلك وجه نافيد أفكاري، بطل المصارعة الذي شارك في احتجاجات عام ٢٠١٨، واعتقل في حملة قمع وحشية للشرطة. تم اتهام نافيد، بعد ذلك بعامين، بقتل حارس أمن أثناء أعمال الشغب الفوضوية وقمع الشرطة الذي أعقبها، ونُفّذ فيه حكم الإعدام.

كانت العادة، في العقد السابق، أن يقود طلاب الجامعات والشبان والشابات من الطبقة الوسطى الاحتجاجات التي شهدتها إيران، حول موضوعات الانفتاح السياسي والحرية الاجتماعية، لكن الاحتجاجات التي أتت في عامي ٢٠١٨ و٢٠١٩ كانت أكثر تعقيدًا.

بعد انتهاك ترامب للاتفاق النووي الإيراني الأمريكي في عام ٢٠١٧، بدأ الاقتصاد الإيراني في التدهور، وفقدت العملة الإيرانية قيمتها بسرعة وارتفعت أسعار السلع اليومية، وبعد فترة وجيزة، اندلعت الاحتجاجات إذ حاولت الحكومة خفض الدعم على السلع الاستهلاكية وتعويض النقص في ميزانيتها. انتشرت الاحتجاجات في أنحاء البلاد عامًة، وفي أحياء الطبقة العاملة والفقيرة في ضواحي المدن خاصًة، وهنا كان جوهر اختلافها مع احتجاجات العقد الماضي، فحيّرت المراقبين، إذ لم يكن جوهرها محددًا، بل امتلأت بالعنف ضد المباني والممتلكات، في موجات من السخط الذي نبع بلا هوادة من أبعد أركان المدن.

كان نافيد افكاري واحدًا ممن شاركوا في هذه الاحتجاجات، وقد تمّ انهاء حياته، وحرمانه حتى من زيارة أخيرة لعائلته قبل قتله في تمثيلية زائفة للعدالة، بُثت في جميع أنحاء البلاد، لكن صورته، أصبحت بعد وفاته أيقونة فورية لرجال الطبقة العاملة في جميع أنحاء إيران. أصبح نافيد رمزًا لعنف الدولة ضد الشباب الشرفاء

دعوة للثورة التي رفضت الصمت، حتى في الموت.

يعتقد الكثيرون أن إعدام نافيد كان تحذيرًا لشباب آخرين في سنه وبنيته، للابتعاد عن الاحتجاجات والسياسة، وقدّ أكّد ذلك بنفسه في أحد التسجيلات الأخيرة قبل وفاته قائلاً: “إنهم يبحثون عن رقبة يعلقون عليها مشنقتهم”.

أظهرت مقاطع الفيديو التي نشرها أصدقاؤه قبل موته، الحياة البسيطة التي كان يعيشها، مبتسمًا في صالة الألعاب الرياضية ومحاولًا تقليد بعض الأغنيات مع قريب له… جعلت هذه الصور والفيديوهات نافيد مألوفًا ومحبوبًا، وجعلت الأمة تشعر بالمرارة تجاه العنف الذي تعرّض له من الذين ادعوا حماية الناس.

في موته ،

بزغ نجم نافيد أفكاري كبطل جديد بين أخوانه من الأبطال الپهلوانيين.