Originally published by Ajam Media Collective on January 24, 2013.

This winter has been a particularly rough one in Tehran. For the third year in a row, air pollution has frequently reached highly unhealthy levels, and schools and other public institutions have closed for days at a time in response. Although Tehran’s air quality has been a major issue for decades, never in recent memory has the problem been this pronounced, and never has the site of pedestrians covered in facemasks been this common.

Like most major cities around the world, Tehran’s modern development and growth is occurring at breakneck speed and has led to a host of environmental issues for policymakers and citizens alike to deal with. In addition, due to Tehran’s unfortunate position at the northern end of the Iranian plateau and squeezed up against the Alborz mountain range, polluted air from the city and the suburbs floats north into Tehran and sits stagnant. This phenomenon is aggravated by the cold winter temperatures and low precipitation common to the region, making pollution a major health hazard in the winter.

The Western media never misses a chance to report on any piece of negative news coming out of the Islamic Republic, and true to form every major outlet has had an opinion on the Iranian capital’s air quality in recent days. It is hard to imagine many other cities’ pollution problems popping up as major news in Western capitals, and with the unique exception of coverage of Beijing, especially during the 2008 Olympics- a coverage spurred mostly by the fear that Western athletes would be subject to Third World toxicity rather than concern for Chinese citizens, it seems- there are few examples of such coverage in recent memory.

The reporting on Tehran’s air pollution has been particularly horrendous (with a few notable exceptions). As with most Iran-related news, coverage has not only tended to give the most misleadingly negative portrayal of Iran possibly, but has also been littered with sensationalism and half-truths that obscure many of the major causes of Tehran’s current misery. Additionally, a great deal of the reporting appears to be directly ripped off from this Tehran Times article, with little attribution.

One of the most egregious examples of this kind of reporting is a recent article in The Guardian’s Tehran Bureau section. Co-authored by Saeed Barzin and an unnamed Tehran Bureau correspondent, the piece is entitled “Iran braces for fresh wave of toxic smog,” and it outlines the air pollution problems facing the Iranian capital and other major Iranian cities. The article mentions that two major causes of the country’s air pollution woes are the use of substandard petrol and inefficient vehicles. It further asserts that the number of days a year of unhealthy air in Tehran has doubled as compared to last year. Additionally, a student is quoted as saying the government seems to have “surrendered” and given up trying to fix the problem, while the author asserts political infighting has blocked attempts to expand Tehran’s public transit system which might help remedy the situation.

Upon reading this description, a few key questions emerge which point to major pieces of missing information. Why is it that the problem of air pollution has become so astonishingly severe only in the last few years? If the roots of the problem are substandard petrol and inefficient vehicles, how could the number of unhealthy air days have doubled in the course of one year, given that both of these issues are long-term? Furthermore, given the fact that Iranians have not gone out and bought old, inefficient cars en masse in the last 12 months, how could these issues have possibly emerged only recently? The article offers us a pollution-choked Tehran and a resigned, miserable populace, but no sense of context or history.

The problem is that the authors of this piece omitted a crucial detail for understanding the source of the toxic smog currently choking Tehran’s population.

In the last two years, new rounds of blanket American and international sanctions have been gradually put into effect targeting every aspect of Iran’s economy. The effect has been devastating, leading to major shortages of medicine in Iranian hospitals, precipitating a currency collapse and massive loss of consumer confidence, and generally reducing standards of living for normal Iranians across the board, with no end in sight.

In 2010, a new round of American sanctions were implemented targeting Iranian imports of refined gasoline, meaning that Iranian officials were forced to come up with a way nearly overnight to prevent a crippling energy crisis that would shut down the nation’s economy. As a result of 30 years of increasing levels of international sanctions, the Iranian government has becoming extremely adept at creating low-cost, low-quality alternatives to banned foreign goods.

When faced with the prospect of a disastrous gasoline shortage, Iran did what it does best: it started refining its own gasoline, albeit without the know-how or technological capacity to refine it at internationally recognized safety levels. The result was a health crisis almost completely manufactured by US-led sanctions, as the emergency fuel quickly replaced banned imports but the already mediocre air quality of Iranian cities deteriorated with stunning speed.

Iran was able to make up for the imported refined gasoline denied it by sanctions, but due to the suddenness of the American blow on its gasoline supplies it has still only managed to refine gasoline to an inferior level than previously available.

As a result, no longer are Iranians merely suffering from the economic effects of wide-ranging international sanctions; they are literally choking to death from them. The devastating effect that sanctions have had on medicines in Iranian hospitals in the last year, meanwhile, means that many of the illnesses caused by this same pollution will be nearly untreatable due to the very same sanctions. For those medicines that are still being imported despite sanctions, the currency collapse and costliness of illegal importation means that prices are prohibitively expensive for most Iranians. The end result is an increasingly severe Iranian health crisis almost entirely “made in USA.”

The decision of the authors of the Tehran Bureau piece to omit this key piece of the puzzle is compounded by their decision to give the impression that the Iranian government and the Tehran municipality are doing little or nothing to stop it. Of the points made in this regard, the claims regarding public transportation in Tehran are the most brazenly outrageous.

Since 1999 when the first line of the Tehran metro opened, the Iranian capital’s public transit system has expanded dramatically to become the Middle East’s largest (currently tied with Dubai, albeit with 9 times as many daily riders), with current plans predicting the subway system will surpass the length of New York’s public transit system by 2030.

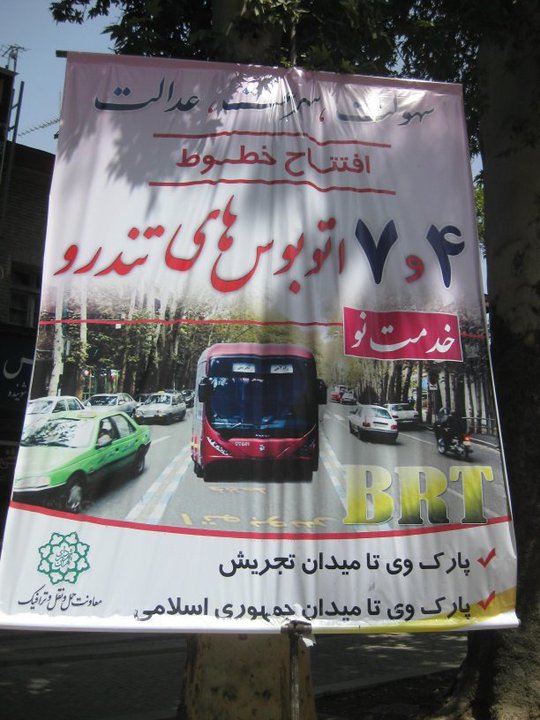

In recent years, Tehran municipality authorities have added large bus-only lanes to major thoroughfares across the city center as part of a push to create a citywide network of BRT (Bus Rapid Transit) to supplement subway coverage. A wide scale public awareness campaign of public transit options has also encouraged Tehran residents to use bikes as a means of transportation, a suggestion aided by the establishment of bike lanes and bike share systems in different neighborhoods across the capital.

Today, daily ridership on the Tehran Metro is around 2.8 million while the BRT line ridership recently hit 1.8 million, compared to the presence of 3.5 million automobiles and 2.2 million motorcycles in the capital.

The result of these changes has been dramatic, as car dependence has been greatly reduced in the course of less than a decade. Tehranis can traverse their capital from north to south and east to west without resorting to the city’s dizzyingly complex and congested highway system.

In 2011 Iran officially became the global leader in natural gas vehicles, with 2.9 million vehicles relying on the clean fossil fuel after a decade of government promotion and support, meaning that many more of the vehicles already on the road are cleaner than ever before. Additionally, in order to combat air pollution the city has introduced anti-traffic measures increasingly common in other major cities, including restricting traffic to even- or odd- numbered plates on alternating days.

Until sanctions on refined gasoline are lifted and Iran improves its ability to produce a local, high-quality alternative (which government officials are currently working on but will undoubtedly take years), however, no expansion of the metro system or limiting of private car use will be able to fully tackle the problem.

The Tehran Bureau article authors offer strangely little of this background to the reader to help comprehend Tehran’s current environmental crisis. Originally an independent news source but then published through PBS Frontline and as of this month the Guardian, Tehran Bureau occupies a unique position as an English-language outlet run by members of the Iranian diaspora that seeks to explain Iran to a global audience.

Given that the Iranian people are currently suffering under an international sanctions regime matched only by those enforced against Iraq in the 1990’s and by Israel against Gaza in the 2000’s, it is particularly shocking that Iranians abroad find themselves complicit in a campaign to demonize some aspects of Iran while ignoring many of the root causes as well as the efforts of many Iranians to implement innovative solutions.

Undoubtedly, the Iranian government has made many errors in its dealings with the West in recent years and it’s handling of the current economic crisis. But we must not allow these errors and current policy failures to obscure our ability to recognize the devastating cost of sanctions on Iranian society. Given the fact that the misery of the Iranian people has been in recent years compounded more than ever by Western sanctions often justified on behalf of the Iranian people themselves, those intending to report on Iran have a responsibility to fully investigate and bring to light the effects of these sanctions.

Iranian-American outlets like Tehran Bureau have a crucial role in this process. Iranian voices in English are few and far between, and those Iranians that have the privilege to describe and explain the Iranian condition to the world have a duty to relay the realities facing Iran today, particularly those caused by the governments of their English-speaking readers. Sanctions are suffocating Iranians and denying them the medicines they need to save themselves; the Iranian diaspora has a duty to tell the world.