Originally published by Ajam Media Collective on August 10, 2013.

It seems that just about every other week another Western journalist “discovers” Iran and its “manically welcoming” people (actual quote), explaining to the world for the fifty-millionth time that contrary to the audience’s assumptions, Iran is a pretty nice place to visit. These articles are utterly predictable in content, mentioning a few stereotypical images (Mullahs! Hijab! Hostages!) before offering a brief slideshow of Isfahan, Persepolis, a mountain village or two, and some young women in North Tehran caked in makeup to reveal the country foreign travelers might discover if they venture “behind the veil.”

My personal reaction to these articles is, admittedly, conflicted. On one hand, given the horrific, sensationalist, and patently untrue myths the Western media systematically perpetuates about Iran and Iranians, a small part of me wells with joy at the opportunity to show Americans that in fact Iranians might be human as well. The proof of our humanity, of course, is that some brave, [white] CNN journalist or Lonely Planet hippie deigned to visit our country for a week and realized that Iran is a pretty decent place. “Look, look,” my heart almost shouts, “not all white people are afraid of us!”

This joy, however, is always tempered by the utter annoyance and disgust I feel at the ridiculousness of needing to prove our humanity to anyone. These projects often reek of an almost 19th century colonial obsession with discovering the “real Iran” and reducing a nation of 70-some-million people to a backpacker’s week-long vacation. These projects are primarily undertaken by Westerners for Westerners, bestowing upon the white [and generally male] gaze a certain universality and objectivity that the narratives of the “natives” never achieve.

These photographers privilege, over and over again, Western visions of Iran, while Iranian photographers themselves are rarely if ever predominantly featured in the same way. These photographs often also serve an implicit political purpose, offering images that suggest a repressed and backwards people and in the process readying the Western public to support their “liberation” through bombs or sanctions. Photography has had a troubled relationship with colonialism and militarism since its inception, and in the case of Iran as in many other places it continues to be so.

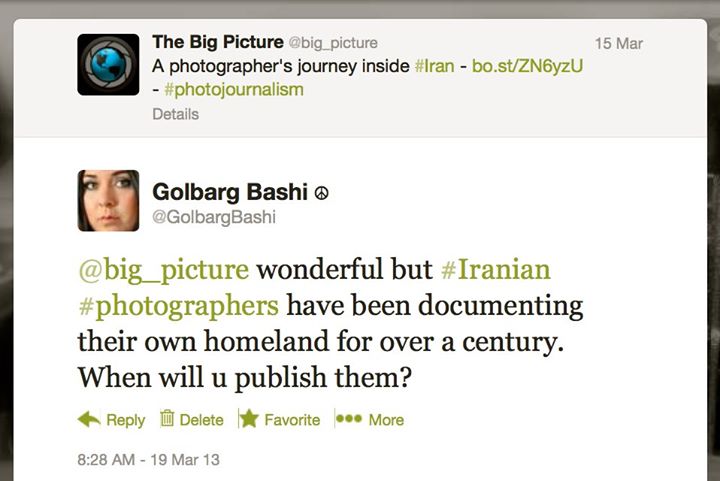

As Iranian-born feminist historian and photographer Golbarg Bashi commented sarcastically in response to yet another article about a foreign journalist visiting Iran, “After all of these years… all of these films, paintings, books, photographs… it’s still assumed that Iranians are just waiting for some guy from New Zealand or America to take pity on us and go out of his way to show the world, ‘a real glimpse of this strange and bizarre land.’ Thanks so much. Really, you’ve outdone yourselves!”

Iran is a complex country like any other and it cannot be captured by stereotypical images of fanatical Muslims nor by equally flat, stereotypical representations of an “ancient culture” and alluring women.

The search for the “real Iran,” offers a simplistic logic that begins with the premise “Iranians are not their government,” and finishes by proclaiming, “Iranians are defined by their opposition to their government!” But could it be that Iranians are a people as equally complex and contradictory as any other, and that they are not necessarily encapsulated by images of – alternatively – surly militants or women drinking milkshakes in fancy cafes?

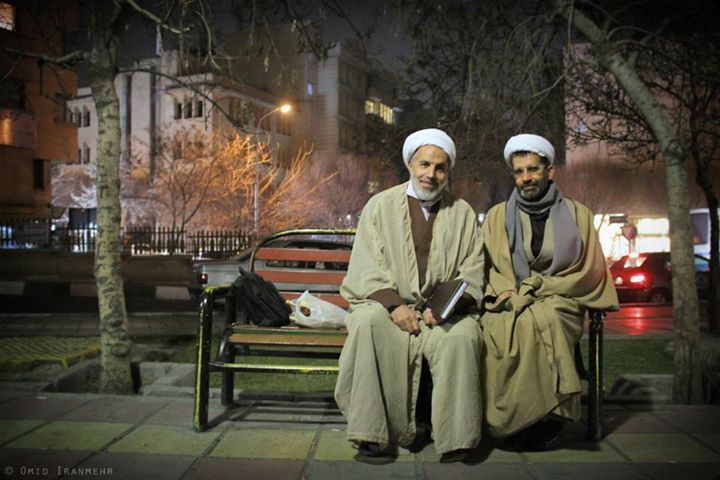

Humans of Tehran offers a well-needed corrective to the clashes of stereotypical images that constitutes so much of Western reporting on Iran. Founded in 2011, the Humans of Tehran project consists of street photography from across the Iranian capital that gives a refreshingly candid look at modern Iranian society. The photographs neither bask in contradiction nor attempt to present a uniform face, but instead reflect the group’s simple, elegant premise: to photograph Iranians as they live their daily lives.

Perhaps this is one of the most novel aspects of the project: by highlighting the ordinary and the quotidian, Humans of Tehran captures surprisingly intimate portraits of exceedingly normal people, images those outside of Iran rarely, if ever, get to see. Humans of Tehran is not preoccupied with proving the humanity of Iranians or documenting their “ancient culture,” and the captions and descriptions accompanying the photographs lack the alternatively zoo-like or pitying tones that characterize much of the “sympathetic” reporting that emerges in the Western press.

Humans of Tehran itself was originally modeled on Humans of New York, the genesis of the “Humans of” series that has since spread to every continent and whose spin-offs emerge daily in locales both near and far (Humans of New York actually visited Iran in December 2012).

Since Humans of Tehran’s emergence, meanwhile, a handful of other projects have emerged in Iran’s other major cities, and today one can explore the streets and people of Shiraz, Esfahan, Tabriz and others via their Facebook pages. Hell, even the Tehran Municipality has gotten into the act with its own photoblog. These projects have all emerged independently, but each offers a unique vision into the society and cultures of Iran’s major cities and from across class, ethnic, and gender backgrounds.

Humans of Tehran itself is a surprisingly low-budget affair, run primarily by Tehran-based Omid Iranmehr and Nooshafarin Movaffagh as well the as site’s original founder, Shirin Barghi, who leads from her current base in New York City. Meanwhile, a regular group of Tehran-based photographers numbering around 5 or 6 contribute content occasionally. Fittingly, the collective is organized entirely electronically. While in Tehran recently, I sat down with Omid to discuss the project, its goals, and its history in Persian, which I’ve translated below.

Alex: Tell me about Humans of Tehran. What are your goals with this project, and how does the medium of photography assist you in achieving those goals?

Omid: Photographs are an international language. It’s not necessary for someone to speak a specific language in order to understand them because what you see depicted resembles exactly what exists. Photography offers us a way to make ourselves known and to represent our world to others. This is a reality that we live and experience, and our reality differs completely from what the world thinks!

If someone were to come up to and try to explain what they think life in Iran is like based on the images that circulate in the West, honestly, I would have no idea that they were even speaking of Iran! The stereotype is really that different from reality.

The project itself is a completely independent effort and it strives to show exactly what exists, to show what is. In some ways, it’s similar to Ajam’s own work!

A: I’m interested to know more about the process of taking pictures itself. How do you choose your subjects? What do you say when you go up to people?

O: Well, it’s difficult to say exactly. Usually I will be walking somewhere and maybe I’ll see someone, and I think to myself: I should take a picture of this person in this environment; they suit the space, and the space suits them.

Sometimes I’ll go up to someone or a couple, for example, and the woman will say yes but the man will oppose getting his picture taken. Or he’ll say, “No, just take a picture of our child.”

A few days ago, I went to Azadi Square (“Freedom” in Persian), and I saw a woman who held a small child beside her, fast asleep. I thought it was an interesting shot, a child asleep and dreaming in Freedom Square. So I approached and asked if I could take a picture, and she said, “for what?” After I explained the project, the woman looked at me a little strangely and said, “Well, you can’t take me but you can take the child.”

So we spoke for a bit, and then her husband showed up. I explained to him the project, and he responded, “Well don’t photograph me, but you can photograph my wife and child.” So he refused to be photographed, and then the woman had also refused. From three original people, I ended up with one. So the woman held up her child in front of her so that the camera couldn’t see her, and I took the picture of the child and her hands. I have no explanation for why none of them wanted their photos taken, but that they didn’t mind if their child had his photo taken!

A: But why? Why is it that people might only want their children’s photos taken, but not their own? Is it a cultural thing?

O: It might be. In the sense that the beauty of a child is something everyone is okay with capturing and showing, but the beauty of a man is something that should not be shown, for example.

Once in Mirdamad, I saw a man selling fire-roasted beets on the street. He said he had been born in Mashhad but had come to Tehran to work and sell beets. Usually, if someone is selling something and I take a picture, I buy a little bit of whatever they’re selling when I take the picture. But he told me I didn’t have to buy anything, but he just wanted me to give me a copy of the picture the next night. So I said okay. I bought some beets, anyways, and then we talked for a while. When I readied to take his picture, he told me not to photograph him, but only the beets! I said, “No, you yourself have to be in the photo! It’s called Humans of Tehran, that means people have to be in it.” He responded “Okay, but I won’t look at the camera. Take it exactly like this, as if I had no idea you were taking my picture.”

A: Why?

O: I don’t know! He gave no explanation. But the problem is that if you go down that road, people start saying, “Okay, take me from this side and take one from that side,” as if it’s a photo shoot!

Often really interesting things happen. A few days ago I went to Café Naderi, the famous old coffee shop downtown. I went and was drinking tea there. I saw a group of women and men in their 30s and 40s. I saw that they gave their phone to a neighbor to take a picture. Seeing that they wanted their picture taken, I went up to them, and after explaining the project they consented to having their photograph taken.

I asked if they were family and they replied, “We were all in university doing our graduate studies in the early 1990s together. 21 years later we decided to have a reunion. We announced it on Facebook and told all the people of that class to come. And so we came!”

A: What’s your goal with your work on this project?

O: Through the project, we want to offer a realistic depiction of Iran. As it is now, most things that depict Iran are either extremely exaggerated, especially as they show it to be this really closed-off kind of place that it’s not.

This project allows Iranians to depict their own lives and circumstances. You get to see exactly what exists, both the good and the bad. Not just that it’s great and it’s like Heaven here, but also not just the bad, as if we’re living in Hell. Iran is just like any other country; we have good and we have bad. There are rich and poor. There are people selling on the street, and there are luxury stores. There are stores where people put up pictures of Shi’ite Imams, and there are stores where they put up pictures of Santa Claus.

This is our goal: to use the language of photography to represent our society. Sociology through the means of photography. [Note: In Persian the word “sociology” is composed of a compound that literally means, “coming to know society,” hence here it exists in the most literal sense possible.]

This is our goal: to use the language of photography to represent our society. Sociology through the means of photography. [Note: In Persian the word “sociology” is composed of a compound that literally means, “coming to know society,” hence here it exists in the most literal sense possible.]

A: There is something interesting about the project from two different angles. The first is the one you described, which is how people abroad are seeing these photos and reacting to and interpreting them.

Another interesting angle, however, is within Iran itself. Right now there are not that many projects like this, completely independent projects where people go out into the street and just talk to other people and photograph. People aren’t familiar with the concept of just wandering around and talking to people. It has been very interesting for you all and for the people you interview because the public is unfamiliar with this kind of independent project.

Exactly. It’s something that has never been experienced before. We live in a kind of insular society, in the sense that people tend to be a bit more closed to strangers and are instead focused on their families. So the idea of being seen outside is a new thing. It’s mutual reciprocation; we get to take these photos of these people and show them a different way of being outside, of interacting with people, but on the other hand we also get to learn about our own society by interacting with people we would never otherwise have a chance to!

It also helps people open their minds a bit, to think that they are able to have an independent project of this sort. That an artistic project that also engages in a social way is possible here in Tehran, and it is not only possible in New York.

One of the unique things about this project, is that on top of New York, it now exists in so many countries, every day a new one popping up. It’s something really attractive to me, that it’s creating social networks between different countries. Each one of these projects is led by a person who is trying to show their own city and represent it to the world.

These projects become a kind of potential network for peace. The idea, at its core, is that we should explain our cities and our countries to each other. In this there is the sense of a conversation, of a conversation of images between all of us. We are all using the language of photography to say what we want and to show our own countries. It has become a kind of international conversation of people who on one hand are interested in discussing their own countries and also want to understand other countries.

It is becoming easier to send messages of peace and to communicate with others elsewhere, especially through this shared language of photography. There are no misunderstandings, nothing like that. It is an easy and important way to communicate a message of peace to the world.

A: It’s so important, especially for Iran, right now, under these conditions!

O: Exactly. The image of Iran that exists in the world is not correct.

A: Everyone speaks about you in Iran, but no one speaks with you! No one says, okay you guys discuss your realities and explain what your own lives are like. Everyone else just wants to say, this is who you all are, this is what your lives are like, and these are your circumstances.

O: Exactly. But the reality is so different, and the reality of our lives in Iran looks nothing like what most people think.