Originally published on Ma’an News Agency on Nov. 26, 2013.

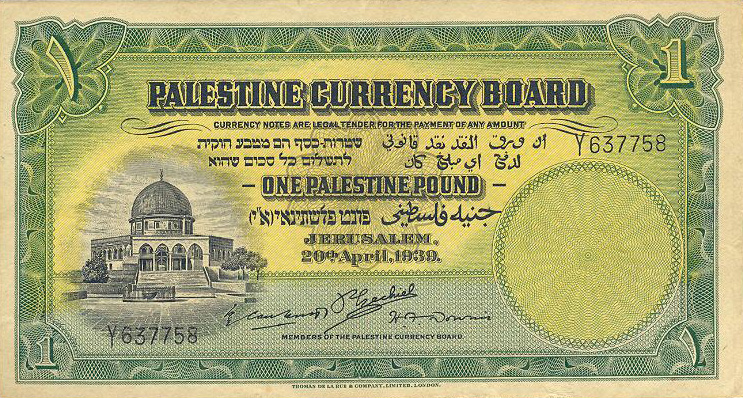

BETHLEHEM (Ma’an) — In markets across historic Palestine, tourists can buy coins and bills emblazoned with the phrase “Palestine pound.”

The bills and coins often catch visitors off guard, a stark reminder of a world that existed prior to the partitioning of the Palestinian homeland in 1948.

Indeed, the Palestine pound gives lie to the oft-repeated Zionist mantra that Palestine was a “land without a people for a people without a land” as it demonstrates the existence of a shared currency used throughout the British Mandate of Palestine for nearly 30 years by Muslims, Christians, and Jews alike.

The Palestine pound is an inconvenient reminder for many Israelis that a cosmopolitan and tolerant society thrived in Palestine before its dismemberment and exile by the emerging Israeli state.

But the creation of the State of Israel on the majority of mandate Palestine and the forced displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, alongside the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza by Jordan and Egypt respectively in response, put an end to the currency’s usage.

After Israel occupied the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in 1967, all of historic Palestine came under the rule of the Israeli lira (and later the shekel), while the Jordanian dinar and eventually the US dollar circulated alongside.

The Palestine pound, it seemed, was fated to circulate primarily in tourist markets, a potent symbol of a national sovereignty whose realization was abruptly halted by Zionist militias in 1948.

Bringing back the Palestine pound

One Palestinian researcher, however, is determined to bring the Palestine pound back, this time as the currency of the newly emerging State of Palestine.”

Since I was in high school, I was wondering why we do not have a national currency,” Jacoub Sleibi explained in an interview with Ma’an.

“At that time, the fees of my high school were paid in US dollars, my pocket money was in shekels, and my father was getting paid in (Jordanian) dinars.”

“This situation was extremely confusing,” he explained.

Not only is it confusing, the circulation of three different currencies undermines the Palestinian economy as well as individual Palestinians’ purchasing power.

“Palestinians have to have three accounts in three different currencies in the bank,” because many are paid in dinars or dollars but have to pay for their daily expenses in shekels. Others are paid in shekels, but have to pay university tuition or other institutional costs in dinars, he explained.

“Households and even investors will have to exchange one currency to another at a certain point, and because there is a difference between the bid and ask prices of each currency, people are forced to lose money in every transaction they make.”

As a result, Palestinians are constantly subject to multiple exchange rate volatilities, as fluctuations in the rate of exchange between any currency can dramatically affect their financial stability.

Sleibi’s research while a master’s student in global finance and banking at Bradford University in the UK examined how the situation negatively affects Palestinians’ livelihoods, and revealed the benefits of a transition to a single currency, the Palestine pound.

In the current situation, when the Jordanian dinar gains strength compared to the Israeli new shekel, the attractiveness of exports increase as well as Palestinian purchasing power. However, an increase in the strength of the US dollar compared to the Israeli new shekel has the opposite effect, increasing the attractiveness of imports and hurting local industry.

The Palestinian economy is thus vulnerable to shifts in multiple exchange rates, leading to a volatile economic situation for Palestinians.

Reducing dependency on Israel

The Paris Protocol of the Oslo Accords governs the issues of a potential Palestinian currency. Signed in 1994, they retain the possibility of an independent Palestinian currency, but insist that this be “mutually agreed upon.”

The current situation perpetuates Palestinian dependency on the Israeli economy, and the circulation of Israeli currency is an economic boon for the State of Israel. The result, Sleibi argues, is bad for Palestinians on all levels.

Exchange rates are set by the Bank of Israel, leaving Palestinians subject to outside control and manipulation. This was particularly striking in the 1970s and 1980s, when Palestinians were held hostage to the hyperinflation of the Israeli currency.

Under the Oslo Accords, Israeli products are provided near unimpeded access to the Palestinian market, while Palestinian goods fail to receive the same access to the Israeli market.

Currently, around 70 percent of imports come from Israel, and fluctuations in currency often favor Israeli products at the expense of Palestinian industry. The system of Israeli restrictions on movement within the West Bank, meanwhile, slows down trade and inhibits the ability of outside products to enter.

Palestinian trucks are repeatedly inspected, unloaded, and re-loaded, a time consuming process. Israeli trucks, however, do not face similar restrictions when passing through the West Bank.

A United Nations Conference on Trade and Development report from 2011 highlighted how Israeli control over the Palestinian economy forces the Palestinians into a situation of dependency on Israel by limiting their ability to conduct trade with other countries.

“The restrictions imposed on the movement of goods to/from/within the West Bank and Gaza have stifled the emergence of an export sector capable of contributing to economic development.”

“Steady access to global markets at normal cost is not only of critical importance to Palestinian economic development, it is actually a precondition for such development to take place,” the report argued.”

The Palestinian private sector continues to be constrained by years of restrictions on movement and access, blockade, extremely limited access to external markets to export goods and import production inputs, and shrinking capital and natural resource bases,” a direct result of Israeli restrictions of Palestinian exploitation of their own natural resources and freedom of trade and movement.

‘We have a right to do it. And we can do it’

Even if these restrictions persist, Sleibi says that his research shows that the re-introduction of the Palestine pound would lead to a major strengthening of the Palestinian economy and of local industry.

“Every state should have its own currency, and I believe that we in Palestine should have a Palestinian pound.”

Sleibi envisions the Palestine pound being pegged to the Jordanian dinar. Its very existence, however, would mean that Palestinians would not be forced to constantly convert their money between different currencies, losing all the while.

Israeli products would also be forced to compete on a more level playing field with Palestinian or international products, and would not have an unfair advantage in the Palestinian market as they currently do.

“The Palestine pound will give more respect to Palestinian products” and will increase the impetus to buy local products, Sleibi argued.Sleibi envisions the transition taking place gradually.

“We could adopt one of the currencies before moving to the Palestine pound, because its better to transition to one currency first before creating a fourth one,” he said.

He suggested that moving to the sole use of the dollar could be a first step towards transitioning to exclusive use of the Palestine pound.”People are already confused (with the current situation),” he argued.

“This way the transition will be smoother.”

Sleibi has already been in contact with officials at the Palestinian Monetary Authority, and is optimistic about their commitment to the idea.

“They’re interested, there’s no doubt about that.”

Given that the current situation strongly favors the Israeli economy and creates a situation of forced dependency on Israel, however, it is hard to imagine Israel readily accepting the currency proposal.

“I don’t know if Israel will allow it,” Sleibi said.

But if they prevent the Palestinians from establishing their own currency, Sleibi continued, “they will lose the battle globally.”

“It is a Palestinian issue. We have the right to do it. And we can do it.”