Originally published on February 10, 2014 by Ajam Media Collective.

“I Am Nasrine” is the first feature length-film from Iranian-British Director Tina Gharavi. Newly available on DVD, the BAFTA-nominated film follows two Iranian siblings as they struggle to make new lives for themselves in the UK. It can also be watched online here. SPOILER ALERT: Although the following piece tries its hardest not to give too much away.

Iranian-British director Tina Gharavi’s new film I Am Nasrine is a groundbreaking tale of the lives of an Iranian brother and sister (played by Micsha Sadeghi and Shiraz Haq) who flee to the United Kingdom and find a world that looks very little like anything they expected. Ajam Media Collective sat down with Gharavi in Paris to discuss the film and the difficulties involved in giving a complex account of an Iranian immigrant story for a British audience.

From the outset, I Am Nasrine defies stereotypes and simplistic explanations of the motives and desires of migrants. The main character Nasrine’s parents force her to leave Iran against her will after she has a nasty run-in with the morality police, and she is accompanied by her brother, Ali, to start a new life abroad.

Relocation by immigration authorities to the public housing projects of an industrial northern English town, however, shocks the two middle-class siblings, as they find themselves isolated in a dark, impoverished and unfriendly new setting. The pair eventually find love and opportunities in their new home, as Nasrine befriends a girl from a local English Traveller community and Ali finds companionship, work, and romance in the city center. But the spate of Islamophobia that overtakes the town following September 11 combined with a pervasive and violent homophobia, leads the duo to a tragic end.

“England is portrayed in a very brutal way”

Director Tina Gharavi, an Iranian immigrant to the UK herself, has few delusions about the realities of modern working-class British life, and the film spares no punches to reveal the unforgiving realities facing the young siblings both before and after their flight abroad.

“England is portrayed in a very brutal way,” she explains. “You almost feel like the Iranian government could show this film to potential immigrants and be like, ‘This is what happens to you if you go! You end up in a rubbish house, people are racist and they’re not very nice!’”

At the same time, however, Gharavi stresses that the film shows the complexities of the immigrant experience in England, highlighting both the positives and the negatives. The film is “a love letter to the North East, which has many important qualities that I cherish and admire. It’s a hostile land but people are very open, too.”

One of the most striking aspects of the film is how nobody is spared a brutally realistic depiction, including the Iranian authorities. When I asked her about how Iranians have responded to the film, Gharavi pointed out that she never even imagined an Iranian audience for the tale.

“The audience of the film is really imagined as a young, British teen audience. They’re the primary people I was thinking about.… This is more of a film about England than it is about Iran, and about the asylum experience when the characters arrive…. I pick it up where they have to leave, and they have to make this journey, and survive. And survive when they arrive.”

One of the film’s main strengths is the ambiguity that pervades the plot. Nasrine’s flight from Iran, although the result of a horrible encounter with the police, is actually a direct result of pressure from her parents. These are not idealistic stock characters yearning to be free, but real people in a difficult situation who are forced out for a variety of reasons. As Gharavi explains, “There is always this idea that every young Iranian wants to leave Iran, but I was quite convinced that there are many people who feel that there is good work for them to do in Iran, and that they want to stay.”

“They should be thankful just to be here”

Stories of refugee migration involving Iranians and other Middle Easterners have emerged in the last decade as a battleground between conflicting narratives of the region and of its relationship to “the West.” These migration narratives often follow a predictable pattern; reducing the complexities and difficulties faced by refugee and asylum-seekers in their search for a better life into stories of flight from the backwards, oppressive East for salvation in the progressive, free West.

These narratives, of course, erase the complicities of their audiences in the violence and economic deprivation that leads many migrants to flee in the first place, displacing unhappy reminders of colonialism and contemporary political intervention abroad with self-serving tales of the West’s warm and fuzzy bearhug of the downtrodden. Not only do they obscure the relationships of Western audiences to their migrant protagonists; they are also often replete with wild misrepresentations. The difficulties of migration do not end when the migrant flees the homeland or even once they arrive at their destination. Indeed, the systemic obstacles to social integration they face as a result of Western reception regimes and unsympathetic host populations often work to prolong the nightmare of flight and reconfigure it rather than actually resolve it.

As Sima Shakhsari highlights when discussing the experiences of trans* and queer Iranian refugees, it often seems that violations of the rights of Iranians are hypervisible when they occur back in Iran, but somehow invisible when they occur abroad.

Shakhsari analyzes the case of a young Iranian trans woman who was the subject of a documentary about her flight from Iran and arrival in Canada, which the film presents as a tale of escape from the claws of oppression to a successful arrival in the domains of freedom and liberalism. The film, however, fails to tell the viewer that the young woman committed suicide prior to the film’s release, caught between visa regulations and a lack of healthcare that made life a living hell. While the deaths and abuse suffered by Iranian trans individuals inside Iran become the stuff of international human rights campaigns, those who die after having successfully arrived in the West often pass away in obscurity.

While refugees are often granted papers due to the extent of damages done to their bodies (or their ability to convincingly make the case for harm suffered in their homelands), they are frequently not given the ability to provide for themselves (through work permits) upon arrival, as Miriam Ticktin reminds us in the French case. Thus, refugees are treated with a limited understanding of humanity, focusing only on biological functions and stripped of their socio-political lives. These liberal humanitarian regimes often create Kafkaesque bureaucracies that selectively choose “ideal” refugees, restrict their mobility, and prevent them from working, organizing, or acclimating. This creates a sort of legalized limbo where refugees are allowed to exist, but not much else.

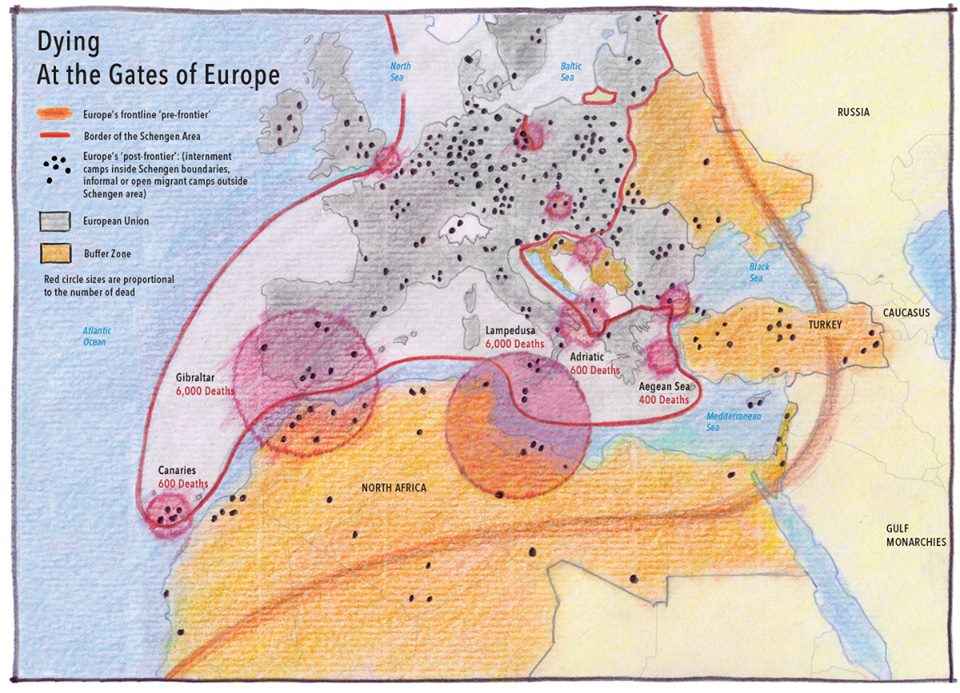

These details, of course, disrupt the narratives that many in the “West” like to tell about themselves and do not fit neatly into international human rights campaigns purporting to save Iranians from an oppressive regime. Similarly, young Syrians or Libyans killed defying authoritarian regimes become martyrs, while those who die in the passage across the Mediterranean wind up as dead bodies photographed splayed across Italian beaches.

***TRIGGER WARNING: PHOTO OF DEAD BODY***

The selective visibility of migrant bodies, of course, is not incidental, but is instead an integral part of a self-congratulatory project of Western liberalism that configures even the slaughter of those trying to reach its shores as proof its civilizational superiority. Even reports of the incredible suffering of migrants often fail to induce emotional responses, instead eliciting all-too-common retorts such as, “If they hate it so much, why don’t they go back to wherever they came from?” or, alternatively, “They should be thankful just to be here.”

But what of those migrant lives and experiences that do not fit the model of a flight from Eastern backwardness that finishes with ascension to Western paradise? Who tells their stories?

Between Roma and Immigrants

When the main characters of I Am Nasrine arrive in England, they are astonished to find a society in post-industrial decline and gripped by poverty, xenophobia, and homophobia. Gharavi offers a narrative of Iranian migration that is strikingly different from the majority of the self-representations produced by the Iranian diaspora. Racialized as brown “Others” and lumped in with immigrants as well as English Roma, Nasrine and Ali find themselves pulled into the worlds of distinct “brown” racial communities that exist on the margins of British society.

While Ali finds his way into a world of South Asian and Arab immigrant male camaraderie, Nasrine befriends a girl from a Traveller community. Travellers are an historically nomadic group in England that share many features with Roma communities (previously called Gypsy communities) across Europe.

Nasrine’s relationship with the Traveller community offers an unexpected critique of British anxieties about immigration and assimilation, for the film shows quite clearly the extremely marginalized position of this white, British minority. The Traveller community’s existence troubles any notion of a unified, utopian, happy British “we” that existed prior to immigration, and lies bare the notion that immigrant difference is at the root of the state’s failure to address social needs or to combat anti-immigrant hysteria. But the existence of Roma, the British other-within, is part of a larger critique of anti-immigrant hysteria that Gharavi pushes forward with the film.

As Gharavi recounts, “There’s so much immigration that’s happened, and yet today it’s only visible immigration that seems to be the problem. But the island is very porous, and it has had many waves of immigration over history. This isn’t a new thing.” These complexities of history, however, are erased by a collective memory that forgets those parts too inconvenient to remember.

“The immigrant is often threatening to the indigenous population because they can hold up a mirror to society in a way that if you’re a part of the society itself you can’t see as easily,” Gharavi explains. “And then if you’re here, you have to be co-opted before you’re allowed to speak. So they silence migrants for a long time because they don’t want to hear what you have to say about them. ‘You’re just lucky you’re here!’ they say.”

“What are you, gay or something?”

Just as constructed notions of racial and cultural difference in immigration buttress a certain narrative of the West-as-safe-haven, stereotypical notions of Middle Eastern sexualities also figure prominently in the grand narrative of immigration. Western imaginaries of queerness and Muslims intersect in the film in the figure of the marginal, queer immigrant. One of the film’s protagonists enters into a relationship with a local individual of the same gender, creating a tense situation in the housing project where the siblings live. Their status as brown foreigners liable to perpetrate acts of terrorism combines over time with their illegibly and ambiguously queer sexual and gender presentations in the community, making their situation increasingly untenable.

The fact that their desires are suspiciously illegible to the community only adds to the sense of their outsider status, for the fact that local bullies cannot figure out what exactly is wrong or off about the two siblings (“What are you, gay or something?”) creates a heightened, uncomfortable tension in each interaction. Their lives and relationships in the community grow increasingly unstable until it all erupts in a pivotal, shocking moment of violence that cuts the migration narrative short in a pool of blood on a Newcastle sidewalk.

The murder leaves the viewer with a disturbing and uncomfortable awareness that it is impossible to discern the exact motive of the killing. Was it homophobic? Was it Islamophobic? Was it xenophobic? Does it even matter? Why is our first response to figure out what box on the hate crime form we should check in order to make sense of a senseless tragedy?

This implicit critique of a liberal politics of identity — and the categorization of human life that it entails — is a thread that runs throughout the film, drawing parallels between the bureaucratization of life that immigration necessitates and the social formations that similarly indicate where and with whom an individual is supposed to be.

The catalyst that sets Gharavi’s narrative into motion is an act deemed to have violated moral convention, and thus requiring correction. In the case of the first act, the event occurs in Iran, and the arbiter of morality is the state. Ironically, the narrative also ends with an act intended to be such a correction, a cleansing of the British housing estate of its unwanted others. In this case, however, the correction does not target a single act but a certain type of brown, immigrant, and illegibly queer life that was deemed to be in violation of local moral convention by its very presence. The farther that Gharavi’s protagonists travel to escape moral indictment, it seems, the more potent its effects became.

The tragedy of the film is not one that can be easily limited to English housing estates or the plight of Iranian emigres. Indeed, this tale of migrant survival and struggle is far more universal, a searing indictment of the limits of liberalism and the failure of international and local humanitarian bureaucracies — as well as receiving societies as a whole — to effectively understand migrants as complex human beings. I am Nasrine is a stunning narrative of migration and struggle that rarely allows the viewer a moment to feel at ease. And for this, it is a triumph.