Originally published by Ajam Media Collective on Feb. 23, 2015 and again in Women in Islam journal on Sept. 9, 2019.

What does an Islamic urban space look like? This question has dogged intellectuals and authorities in Muslim-majority lands for centuries, but in recent decades has acquired a renewed sense of urgency amid the emergence of modernizing Islamist political movements.

These groups have not only articulated new visions of the public sphere, mass politics, and economy, they have also increasingly found themselves in positions of authority to shape the cities, regions, and lands they work in. As these groups have found themselves in control, the revolutionary mandate (and widespread protest slogan) to imagine a politics “neither East nor West, but Islamic” has taken on new meanings, forcing leaders long focused narrowly on legal or constitutional change to recognize the more diffuse and institutional nature of power, and how much the production of space is a part of it.

This process has of course not been universal nor necessarily parallel among Islamist political movements, and it is just as nonsensical today to speak of a unified approached to Islamic urban planning as it is to speak of a unified Islamic politics. But at the same time, approaches to urban planning are developing whose features highlight the often-contradictory assumptions and understandings of citizenship that prevail among Islamist actors. Particularly in countries where modernizing Islamic movements have become institutionalized and bureaucratic, ideological logics have coalesced — as in any other bureaucratic apparatus of control — and tendencies have asserted themselves.

No case provides a better example of this than Iran, where explicitly revolutionary, modernizing approaches to producing Islamic space have emerged in the four decades since the Revolution. In this short essay, I will discuss some of the changes that have occurred in Iranian urban space in the 20th century with a particular focus on their gendered implications, before briefly introducing two dominant approaches to public space in contemporary Iran.

Gendering Tehran

The Iranian Revolution of 1978-9 is often imagined in terms of a binary secular/religious distinction, positioning that which came before — secularism — against that which came after — religious fervor — in order to explain the rise of Khomeini and the ensuing establishment of the Islamic Republic. This explanation — proffered both by supporters of the Revolution as well as its detractors — obscures far more than it explains, however. One of the key arenas in which we see the complex legacies of both the “secular” Pahlavi regime and the “religious” Islamic Republic is gender politics and the public sphere.

Since the Revolution, Iranian urban fabric has been reshaped to both reflect and produce ideals of modern Islamic citizenship as understood by various political actors including the central government, the municipality, and other authorities. These changes can be seen most markedly in the capital, Tehran, a metropolitan area of around fourteen million that has emerged as a laboratory for the rest of the country in urban planning.

The city has been marked by a wholesale reconstitution and realignment of the public space along a gender binary model, such that many public institutions are segregated in some way and the morality police regulate spaces that lack a physical architecture of gender dichotomization (like parks and streets). Paradoxically, this realignment of space has actually facilitated the movement of women in the city, particularly those from religious backgrounds who previously hesitated or were prevented from entering the secular, mixed public sphere.

Prior to the Revolution, the creation and institutionalization of an explicitly secular modern public sphere under the Pahlavi dynasty in many ways reinforced traditional limitations on women’s access to the public sphere while simultaneously constricting the private sphere. The average urban household in 1900 was a large, extended family living together in a communal dwelling in the densely-populated neighborhoods of winding streets that characterized Iranian cities historically. In this context, women traditionally spent much of their time together or in the alleys between homes that were a kind of semi-private space. But urban reforms beginning in the 1870s, modeled to a great extent on Haussmanian reforms in Paris, introduced long, broad boulevards and set the stage for the development of Iranian cities until the present.

These reforms were followed by a series of culturally Westernizing regulations in the 1930s, including clothing restrictions that banned the veil and imposed Western dress on men. There are many stories, for example, of women who were banned by their families from leaving the home after the hijab ban in the 1930s (as well as the hundred thousands of Iranians who emigrated), while anecdotal evidence suggests many women also stopped leaving the home of their own will in order to avoid being stripped in the streets, as police had been ordered to do to offenders. Although the hijab ban was eventually reversed, it continued to be enforced in more subtle ways for decades — through dress codes and informal discrimination, for example. The ban also set a precedent of government authority over clothing and specifically over women’s bodies, irrespective of the women’s own wishes or those of her family.

Spatially, during this period, Iranian women increasingly found themselves living in smaller and smaller apartments without extended family networks. While for some a wholesale acceptance of the Shah’s idealized form of modern gender norms by themselves and/or their communities allowed access to education, work, and opportunities more broadly, for the vast majority of conservative Iranian families, the imposition of the secular public sphere created a world beyond the door (or beyond the alleyway) that was scarcely recognizable. Unsurprisingly, then, while a small number of Iranian women managed to benefit from the changes supposedly enacted in their favor, for the vast majority these reforms were hardly liberatory.

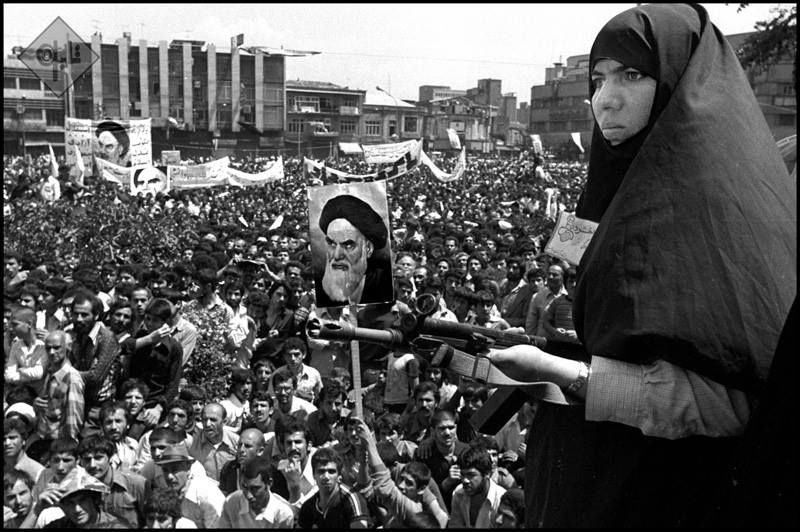

The imposition of gender segregation and the “Islamization” of the Iranian public sphere more widely, however, dramatically overturned the trends of the century prior. First and foremost, as a popular revolution, the leaders that came to power in 1979-80 had a widespread public mandate that was validated through the mass support from both genders manifested during the Revolution. New leaders — principally Ayatollah Khomeini — looked favorably upon women’s participation in the struggle, particularly during the heady days of the revolt when every protester counted.

The physical presence of women’s bodies in the streets translated into a growing recognition of women’s integral right to take part in the political process. As Iranian historian Minoo Moallem has noted, while the ideal woman of the Pahlavi era was defined as secular and modern by her visual availability to the male eye, Revolutionary femininity defined itself as veiled and publicly homosocial. This inversion of the Pahlavi narrative of unidirectional Western modernity as embodied by women’s dress was often articulated through the donning of the hijab as sign of protest, including by many women who did not otherwise cover their hair.

Despite initial hesitations, leaders began to articulate a vision of Islamic governance that institutionalized women’s rights, and traditional patriarchal restrictions within the family—often articulated in Islamic idiom—began losing their potency. As women who had taken part in the revolution began asserting their rights within an Islamic framework to protest, study, and work with government support (including a massive literacy campaign targeting women across the country), massive changes and shifts in power ensued within the family structure.

For conservative families, the imposition of gender segregation in particular was a reassurance that it many ways opened the doors to millions of women to education and work opportunities, and produced a dramatically novel understanding of women’s relationship to public space that was far more expansive. Whereas in 1979, less than one percent of women finished university and around twelve percent were in the workplace (around one-third of whom were underage child carpet weavers), less than forty years later about fifty-five percent finished university, a rate higher than in the United States. Statistics suggest that the percentage of women in the workplace, meanwhile, has increased significantly, and possibly tripled.

This is not to suggest that work and school are absolute indicators of some idealized notion of “liberation;” as Roksana Bahramitash has noted, a least part of the rise in women’s employment can be directly tied to the imposition of neoliberalizing reforms in the 1990s. But at the same time, the incredibly rapid “normalization” of women’s presence in the public sphere can hardly be ignored, nor can it be separated from the ideological and spatial transformations of the Revolutionary period.

The Islamization of public space in Iran can be understood as a collapsing of the public and private spheres. The enforcement of rules of morality in public space, for example, was a virtual extension of the family’s control of individuals’ bodies in the public sphere. It follows that if families feel that the public sphere maintains such control over individuals, however, objections to women’s presence and participation in that sphere lack merit. Indeed, during a series of about two dozen interviews I conducted in Tehran in 2011-12 with women who were the first women in their family to attend university and did so in the 1980s and early 90s, I found that more than half cited such changes as being among the main reasons they felt they had been able to receive educations compared to prior generations of women in their families.

The enforcement of hijab in public space was linked to the introduction of an Islamic concept, the mahram/namahram distinction — in regulation. This distinction delineates a gendered line between women as well male members of the immediate family on one hand, and unknown men on the other. Thus women were legally mandated to cover their hair and bodies, and men their bodies but not their hair, in public in order to ensure this distinction, while in the private sphere it did not apply unless namahram were present. This distinction not only applied to clothing/visiblity but also to relationships themselves, as unrelated women and men interacting in the public sphere became liable to questioning and fines.

This physical delineation of homosociality in the public sphere is predicated on a heterosexualizing gaze, whereby the state’s enforcers see all heterosocial relations as already fraught with the potential for heterosexuality. It is this fear — of heterosocial temptation, of desire, and of adultery — that inspires the police’s zeal for maintain public homosociality as normative, i.e. that relationships in public take place primarily between members of the same gender. For queer Iranians, the authorities’ heterosexualizing gaze actually creates certain opportunities, as close relationships between members of the same gender are normative and considered ideal. The strict gender division also allows understandings of masculinity and femininity to be quite expansive in certain respects, particularly when compared to most Western contexts.

As in many countries around Iran, it is not uncommon to see men or women holding hands, embracing, or cheek-kissing in public with members of the same gender, and these displays are neither policed by authorities nor are they considered socially abnormal, allowing affection and intimacy between friends and/or lovers of the same gender to pass unnoticed. Indeed, an argument could be made that Iranians who seek to publicly display heterosexual intimacy face more discrimination in Iran today, even though the institution of marriage provides them a sanctuary in the private sphere that queer Iranians do not have access to. For trans* Iranians, the strict sex binary also opens certain opportunities, as the government funds the transitioning process in order to ensure that those who see their bodies as existing on the wrong side of the binary have the tools needed to ensure their ability to fit on the appropriate side.

Of course, this gender binary is also extremely restrictive in many ways that it is difficult to discuss in this limited space. For trans* Iranians who are not interested in transitioning or for genderqueer Iranians, for example, the state’s relationship to gender and sex is extremely problematic as it requires biological transition as a condition of legal and religious acceptance. And, while queer Iranians may find some solace in public displays of intimacy, the institution of heteropatriarchal marriage remains socially hegemonic in Iran, and interpretations of the Islamic marriage code that provide for same-sex partnerships are not implemented.

It is important to note that the urban component of the Islamization policies in Iran was extremely brutal as well, particular for those who did not fit into normative understandings of proper binary gender and sexuality roles. The sex work district of Tehran was one of the first to be targeted and was burned down by committees early on in the Revolution, while the thriving cruising culture that dominated the streets around the neighborhood — which were famously host to a large number of young male sex workers as well as cabarets catering to all forms of pleasures — was shut down as well. The compulsory enforcement of the hijab, meanwhile, was and is an obvious violation of the rights of millions of women who chose not to wear hijab, many of whom have vigorously contested the ban.

Although in this piece I have not focused on these aspects of the Islamization of public space, I discuss them here briefly in order to assure the reader that I recognize them. But it is the other story of Iran’s Islamization process in the early 1980s — the millions of women who for the first time in history managed to secure access to the public sphere — that is rarely discussed, and thus the one I have dwelled on here.

Thus far, I have discussed those changes in the urban structure which occurred during the Revolution and immediately following in order to highlight the relationship of ideology to urban space and reflect upon their consequences, the majority of which were quite unforeseen and unpredictable, even by those carrying them out. Since that time, however, distinct understandings of urban space have emerged amid the institutionalization and the bureaucratization of the Revolution. I briefly explore two primary approaches that have developed, as well as the tensions that characterize their relationship.

The period directly following the Revolution is often considered the moment of Revolutionary excess, when the private sphere not only took over the public sphere in terms of moral and bodily regulation by the state, but also when this conceptualization of the private sphere invaded the sacred space of the home as well. Home raids on parties, for example, became commonplace, amid a widespread belief that the Islamization of space and of self needed to occur in all sectors of society. At the same time, it is impossible to separate this approach to urban space from the overall wartime era.

The fervor of the Revolution was interrupted only a year after it began by the Iraqi invasion of Iran’s southwest, bringing eight years of war, chaos, and misery to citizens of both states. Thousands of refugees flocked to Iran’s major cities, and completely unchecked urban expansion — fed by illusory promises of free housing to all migrants — brought Tehran’s population in 1991 to seven million, one million of whom had come in the last five years alone. This was more than double of the population of only twenty years before. The construction and repair of urban spaces, like parks and other public institutions, nearly collapsed during this period, primarily for lack of resources but also justified ideologically in terms of the necessity of a somber atmosphere during war time. The changes to urban space I described above, particularly in terms of Islamization as well as gender segregation, continued throughout the 1980s, although by the end of the decade and the beginning of the 1990s they began to definitively lose their monopoly.

In the 1990s, however, a different vision of Iranian space emerged, along with the process of reconstruction that began after the war came to a close in 1988. This vision was most exemplified by the policies of Tehran’s mayor Gholamhossein Karbaschi. His approach to urban planning shifted focus to the nurturing of a public sphere that was at once Islamic but also institutionalized the growing presence of women in public space. Although his reforms did not explicitly target women, their effects were deeply gendered. He is primarily noted for the mass greening of Tehran that began under his rule, as authorities began taking over vacant lots across the city and building parks, no matter how big or small, in every neighborhood of the city. Between 1989 and 1995 alone, for example, the number of parks leaped from 184 to 680, and the level of green space available on per capita level jumped from two square meters to eleven, despite a rapidly growing population. A slight majority of these parks were located in the relatively poorer southern half of the city.

These parks became the launching pad for the creation of a wide variety of public spaces, such as cultural centers, libraries, and other educational institutions that increasingly began to serve as “third places” for women, who found themselves actively participating in public life but still informally restricted from traditionally male sites of leisure like cafes (although mixed-gender cafes catering to the middle class exploded during this period, equivalents for the working class did not). A survey in the mid-2000s, for example, found that sixty-five percent of users of Tehran cultural centers were women, while informal surveys of parks show high rates of female usage as well. Pocket parks helped recreate the communal spaces of shared dwellings that most Iranians lived in before the almost hegemonic spread of apartments geared toward nuclear families, thus domesticating local public spaces. The rapid growth of the Tehran metro as well as the development of Bus Rapid Transit lines, meanwhile, fostered transit-oriented development and also improved access for those without access to automobiles, who were again more likely to be women and/or working class.

Karbaschi’s approach imagined citizens of the Islamic Republic as an ungendered composite, and he saw his role as fostering participation and access to public space. This was quite different from the dominant approach to planning in the 1980s, which saw Iranians through the lens of the gender binary and imagined mixed public space to be fraught with the potential for heterosexual interaction.

Today, these approaches exist in a state of recurring tension in Iran, as the Karbaschi approach to planning has become dominant within the bureaucracy of Iranian cities while the morality police — who are under the control of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance — continue to police public space in accordance with the approach developed in the 1980s.

To close, I will end with an anecdote from a park that highlights the uneasy coexistence of these two approaches. The local municipalities within Tehran regularly organize concerts and other gatherings in local public parks (built during the Karbaschi era), particularly during the summer. Attending one such gathering on a summer evening a few years ago, I saw a crowd of around one hundred people composed primarily of families sitting on plastic chairs as children danced in front of them beside the stage, where a singer used an electronic keyboard to play “folk music” from different regions of Iran. Dozens of onlookers gathered around the area to watch the scene, nodding along to the music as the heat of summer slowly cooled as a gentle breeze came down from the hills.

Further afield sat mixed groups of young people in the grass, crowds of elderly resting on benches, and occasional groups of Afghan workers in the furthest corners of the park. The standing spectators occasionally swayed to the beat, and some of the parents tried to entice their children to join those dancing around in front by teaching them the motions. The male singer leading the display, however, walked a fine line between enthusiastically enjoining children to come to the front while occasionally reminding parents with quick but explicit asides that those who were not children should remain seated during the performance, gently reminding all those present to uphold standards of Islamic morality befitting citizens of he Islamic Republic. The specter of mixed-gender dancing, particularly given the groups of teenagers watching the scene with bemused expressions on their faces, haunted the performance.

Members of the crowd recognized the fine line between a municipality-sponsored performance that celebrated “national culture,” and sought not to recognize any gendered divisions in the crowd, and the very real existence of morality police, who might break up the scene. The adults taking part in the festival knew that if an over-zealous morality policeman or woman tried to break up the scene, they would be the ones punished for taking part in the festival, while the municipality employees would most likely slink away in the hopes that a mid-level bureaucrat who organized the event would take the hit. For the morality police, in the whole spectacle was deeply fraught with the potential for cruising, mixing, and heterosexuality more broadly.

That day no morality police decided to wander the park to take a look at the festival. A few nights later, however, while I was sitting with a female cousin at a later hour, they stopped by. This time they checked IDs, asking questions, and scared the mixed groups of teenagers and the male Afghan workers from the corners of the park, where a few needles also lay scattered. That night, the “daughter of my paternal uncle” linkage was too distant for the policeman’s comfort, who subscribed to the view that even cousin relationships were fraught with the potential for heterosexuality, and we only managed to escape being rounded up after offering up a story that configured me as a Los Angeles Iranian ignorant of the dynamics of public space in Iran. The tensions between these differently gendered approaches to crafting Islamic public space — to say nothing of the class and national anxieties shared by the morality policy and middle class Iranians vis-a-vis the presence of Afghan workers in the park — play out every day and every night in Tehran parks.

This essay was originally written for The Funambulist, and is included in the book The Funambulist Papers: Volume 2 (Punctum Books, forthcoming March 2015).