Originally published on Ma’an News Agency on April 8, 2015.

BEIT QAD (Ma’an) — Up a small, bumpy road on a hill overlooking the northern West Bank town of Jenin, a food revolution is slowly taking shape.

Blessed with a temperate climate and just a stone’s throw away from the fertile soils of the Lower Galilee, the area has long been home to some of Palestine’s most bountiful agricultural production.

Israeli restrictions on the Palestinian economy, however, have deformed the market, pushing many farmers to produce low-quality produce aimed for export even as locals are forced to rely on expensive Israeli imports.

At a farm near the village of Beit Qad, a new project is spreading a previously unknown vegetable in the area with the hope that it will not only improve access to healthy and natural produce, but also directly challenge the Israeli occupation’s control over the very food Palestinians eat.

The Kale Project is a joint venture by two organizations — Refutrees and the MA’AN Development Center (no relationship to Ma’an News Agency) — that hopes to introduce the leafy purplish-green vegetable to the Palestinian market en masse.

While kale has grown famous in Europe and North America in recent years as a delicious but expensive vegetable for the wealthy and health-crazed, the Kale Project is hoping to harness the vegetable’s nutritional value and its relatively low production costs to inspire a new approach to food for the average Palestinian.

‘Diet and nutrition are tools of war’

Approaching the farm in Beit Qad is a tricky endeavor. Winding north from Ramallah, the road passes Israeli checkpoint after Israeli checkpoint and Jewish settlement after Jewish settlement.

The rolling hills and fertile soil they hide are permanently scarred by the occupation, while the displacement of farmers by Israeli policies of land confiscation has systematically eradicated the generations-old connections between farmers and the land.

Bereft of the intimate knowledge of farming techniques cultivated over centuries and pressured by restrictions on Palestinian exports, many farmers have turned to easy-to-export vegetables like cucumbers, tomatoes, and lettuce. Those left landless, meanwhile, have moved to the refugee camps and tiny apartments in the poorer neighborhoods of West Bank cities.

The result is something akin to a “food desert” in Palestine, where the market is flooded by products of too low a quality to sell in the West or Israel, but dumped onto Palestinians who have no choice in the matter. Prices are still relatively high though as significant amounts of the produce comes from Israel where per capita income is more than 10 times as much.

For Shireen Salah, research and project manager at the Kale Project, the group’s work is as much about health as it is about resisting the occupation’s deleterious effects on Palestinians’ abilities to carry out even the most basic of functions, like choosing their own mix of organic and nutritious food.

“The Kale Project — even though it is not explicitly physically challenging the occupation — is challenging the symptoms of the occupation, especially the devastation of land, the devastation of organic production techniques, and the reduction of crop variety and diversity in Palestine.”

“Diet and nutrition are tools of war, especially in Gaza where an entire population is being kept on a diet by Israel,” she tells Ma’an while driving through the central West Bank en route to the farm.

In 2006, a senior adviser to the Israeli prime minister explained that the goal of the blockade of Gaza was “to put the Palestinians on a diet, but not to make them die of hunger.”

After more than half-a-decade of siege — which continues today — it was revealed in 2012 that Israeli authorities had drawn up documents four years earlier calculating the exact number of calories Palestinians needed to consume each day, in order to ensure that the blockade did not literally starve Gazans to death.

Salah is discussing Israeli food policy when the car crosses a junction leading to an Israeli settlement. Her eyes narrow as she examines the road sign, trying to read between the Hebrew to figure out the road to Beit Qad.

Because roads in the West Bank are under Israeli control, Palestinian towns are rarely marked even though signage for Jewish settlements are regularly maintained and always visible.

After a few moments, Salah remembers the directions. Hesitating at first but later with more certainty, she opts for a road with soldiers every few hundred meters that turns out to be a shortcut.

Staring straight ahead, Salah continues: “This is all a part of boycotting Israeli products. What we are doing with the Kale Project is taking it a step ahead and producing more crops organically that are healthy and challenging the occupation.”

“Not only do we not want to buy Israeli products but also were going to introduce new products and become pioneers in agriculture. I think that’s real food security, and that’s food sovereignty for Palestine.”

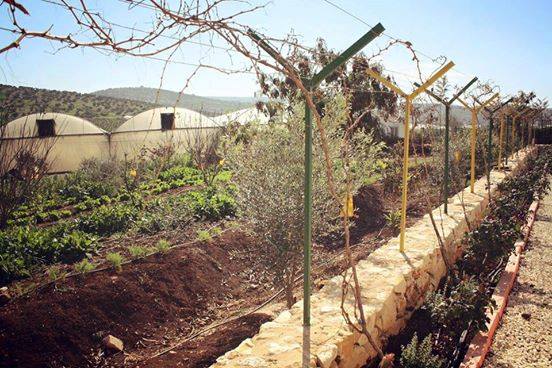

The Beit Qad model farm is run by MA’AN and hosts a number of demonstration projects aiming to promote innovation, ingenuity, and sustainability among local farmers, including the Kale Project.

“The idea of this permaculture farm was to work with small-scale farmers and show them that you can create your own market if you produce organically. You don’t always have to produce to export, because that’s part of the problem, everyone is producing to export because that’s where the money is, while most of the food in the local market is Israeli,” Salah tells Ma’an.

“The idea was to start challenging this discourse and start teaching farmers to produce organically because you produce really healthy food and sell it locally here and be an alternative to Israeli produce.”

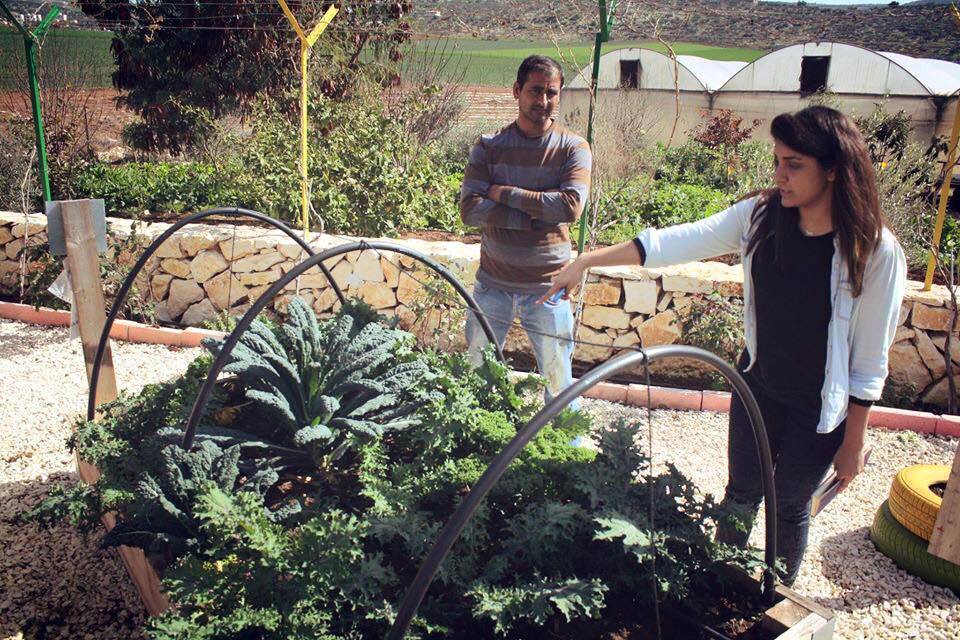

Despite lack of familiarity, growing interest On a bright spring day, project manager Wahbeh Asfour took Ma’an on a tour of the model farm run by MA’AN Development Center where the first batches of kale are being raised.

Despite lack of familiarity, growing interest On a bright spring day, project manager Wahbeh Asfour took Ma’an on a tour of the model farm run by MA’AN Development Center where the first batches of kale are being raised.

The first planting began in November and already three different batches have been grown, each taking about 4-6 weeks. There are three different kinds being grown at the site, including Russian kale, dinosaur/black kale, and the most popular — curly kale.

Known as karnab in Arabic, kale is relatively unknown in Palestine. However, its relative similarity to broccoli in appearance has helped facilitate its slow introduction.

Asfour told Ma’an that the organization plans to have workshops with female farmers from the local region to introduce them to kale’s health benefits as well as planting and cooking techniques. At the end, each farmer will leave with seedlings.

“It’s not just a matter of it being tasty and nice,” Asfour told Ma’an. “At the end you want to see kale planted in people’s home gardens.”

“If they know what it is they know the health benefits, they’ll start eating it. This is how it will spread. But right now, people don’t know what its name is, how to eat it, or how to cook it.”

Despite this, MA’AN sells out every week when it sells the vegetable at its Ramallah office, and the organization has been flooded with requests from Bethlehem, Jerusalem, and even inside Israel.

Ramallah health food restaurant Fitafe has even agreed to include kale in its smoothies, marking a success for the project.But Salah was adamant about ensuring that kale not become an exclusively high-class product like in Europe and North America, but could and should instead reach the masses.

“Kale in the West started as a fad, a very bourgeois kind of crop. But we don’t want that here. We want to reverse that impression and we want more farmers in rural communities to grow it because of its health benefits … We want it to be used in traditional recipes to motivate more ordinary Palestinians to consume it on a daily basis,” Salah told Ma’an.

As a result, much of the project’s growth strategy focuses on trainings with community-based organizations in the West Bank, and they’re planning to expand to Gaza as well.

Currently the kale sells for cheap, at around eight shekels for a big bundle that lasts about two weeks. The price reflects the fact that the crop is not water intensive, especially with the variety of water-saving techniques being put in place at the farm.

Jasser Mahameed, a farmer who works at the site all year round, argues that the use of organic techniques ensures the high quality of the produce and makes it an attractive model for visiting farmers.

“We have a natural farm here and we are successful because of it. It is much better like this (than with chemicals). Because it is natural the flavor is better and the vegetables are healthier. Chemicals are absolutely forbidden here.”

Despite his optimism, Mahameed agrees with the project managers that lack of recognition is the biggest hurdle facing the spread of kale.

“The kale is great. It’s a great product,” he told Ma’an. “But the only problem we have is that no one knows what it is.”

With a little more awareness, however, he believes that kale could be a great success.

Some names have been changed to protect interviewees.