Originally published by Ajam Media Collective on November 12, 2015.

In Karachi, the dream of Pakistan – in all of its glory, misgivings, failures, and triumphs – has become reality. More than any other city in the country, Karachi and its 23 million people manifest the complexities of the story of Pakistan, beginning with Partition in 1947 – when the city’s Hindu and Sikh majority left amidst spasmodic violence and were replaced by a massive influx of Muslim Muhajir refugees from India – and beyond. Articulated in the city’s very urban fabric is the dream of an egalitarian, secular Muslim nation shattered amid widespread class, linguistic, and eventually religious and sectarian discrimination, as well as an increasingly authoritarian and antagonistic political culture.

The culture of violence that has overwhelmed Karachi recently and given the city its fearsome reputation as one of the world’s most dangerous cities is a product of these histories. Even today, when hundreds of thousands flee their homes in Baluchistan or in the Frontier Territories as a result of army and police violence, they arrive in Karachi only to find these same establishments running the show — and apparently unable to prove their particular ideology of “security” can be successful even at the country’s heart.

This is where Exhausted Geographies comes in. This new book, co-edited by Karachite artists Shahana Rajani and Zahra Malkani, explores the complexities of mapping Karachi. The authors illuminate the histories embedded in this city’s urban fabric while at the same revealing the tensions that characterize many of the ways we view mapping as a natural way to see and understand a city, especially one like Karachi.

For the co-editors of Exhausted Geographies, such an approach to Karachi is exactly what is needed at this moment. Rajani and Malkani are part of the Tentative Collective, a Karachi-based collective that aims to create “collaborative works of art” in the city, but for this project went it alone to create a gallery show and printed book that they hope will take the conversations of the gallery space beyond the Pakistani art world. The following is an edited transcript of a conversation between Shahana Rajani, Zahra Malkani, and Ajam co-editor-in-chief Alex Shams.

AjamMC: Your work primarily focuses on art in relation to the city, especially our relationship to geography as citizens or people inhabiting a specific urban environment.

How did you both start thinking about the city in that way, as a text to be read, or a place you’re interacting with? How did you develop a critical lens on geography?

Zahra Malkani: What really propelled me to do so was the huge growth in academic, textual, and visual cultural production that takes Karachi as its subject matter in recent years, especially the amount of discourses being produced about the city in this geopolitical sense, discussing it as the “most dangerous city in the world” versus the more local ways of seeing the city.

Both of us came from this simultaneous experience of going through that same condition – feeling this urge to partake in that reading, but also this exhaustion and disillusionment with that discourse.

Shahana Rajani: We started thinking a lot more carefully while we were away from Pakistan for our masters degrees, when we had that distance from the city but also being able to see how it’s usually represented, especially in the diaspora, and to see the kinds of images and narratives they create.

AjamMC: Why “exhausted geographies”?

SR: “Exhausted geographies” is a borrowed term from Irit Rogoff. Exhausted geographies is this moment when the land or the territory can no longer sustain the claims that are being made upon it. The moment of collapse of the exhausted geographies calls for a turning away from the seeing or representing of space from these singular perspective, and demands a flight from traditional methods of map making.

Her concept highlights the potential of artistic methods to rethink map making so space can be viewed from multiple perspectives, views, planes, and dimensions. We were starting out from this place of exhaustion in this overdetermined city.

ZM: She frames the term so that we can view exhaustion not just as something negative — as withdrawing or opting out — but as a ripe moment of opportunity. She calls it a moment of treason, the moment where you may abdicate a singular perspective through which to see or map the land. In that moment of collapse where the claims no longer hold, you have the possibility to visualize or construct something new through a multiplicity of perspectives or positions.

AjamMC: What are some of the trends or discourses you identify as being hegemonic in discourses that take Karachi as their subject?

ZM: Karachi is seen as the site of completely incognizable violence, a violence that you can’t make sense of. As opposed to actually focusing and making the structure of violence in the city visible, there is more of an emphasis on crime and disorder.

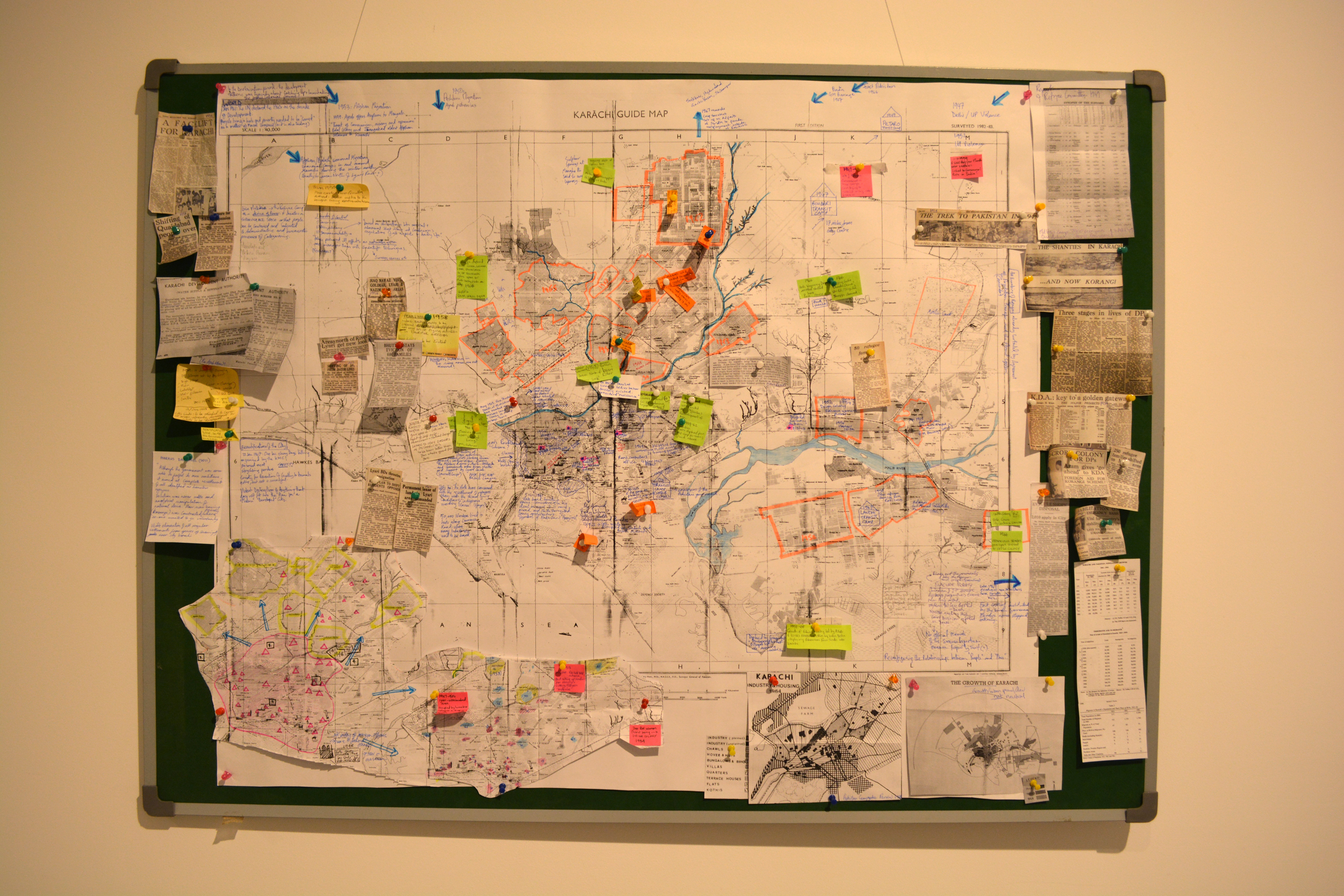

SR: In the past few years, as local newspapers have taken to GIS mapping, the mapping of violence has become a common visual that people read throughout the newspapers.

Whether it is crime maps or no-go areas in the city, or spaces that have been bombed or attacked, there is a constant zoning off of places that are safe and those that are dangerous. Multiple divisions and dystopic imaginings of the city are constantly being created and sustained through mapping.

AjamMC: This book is a critical intervention, particularly in this moment in time in which local newspapers are adopting mapping as a strategy of power. This is being combined, meanwhile, with war on terror rhetoric which sees violence itself as the problem and doesn’t ask questions about the underlying structures that are leading to this violence.

How do you think about mapping as a strategy of power related to Karachi?

ZM: In the book, we were grappling with the larger question of the limitations of mapping, and trying to think about different ways of visualizing the city that take those into account. We went about that by experimenting and opening it up in a cross-disciplinary way, bringing more artistic methods of visualizing into conversation with the work of architects or urban planners. That was one of the big motivations for making this as interdisciplinary of a project as it was.

SR: It was really important to come up with a framework to trace the epistemic violence that has occurred in cartography and silences and erasures around different practices of mapmaking that have been forgotten.

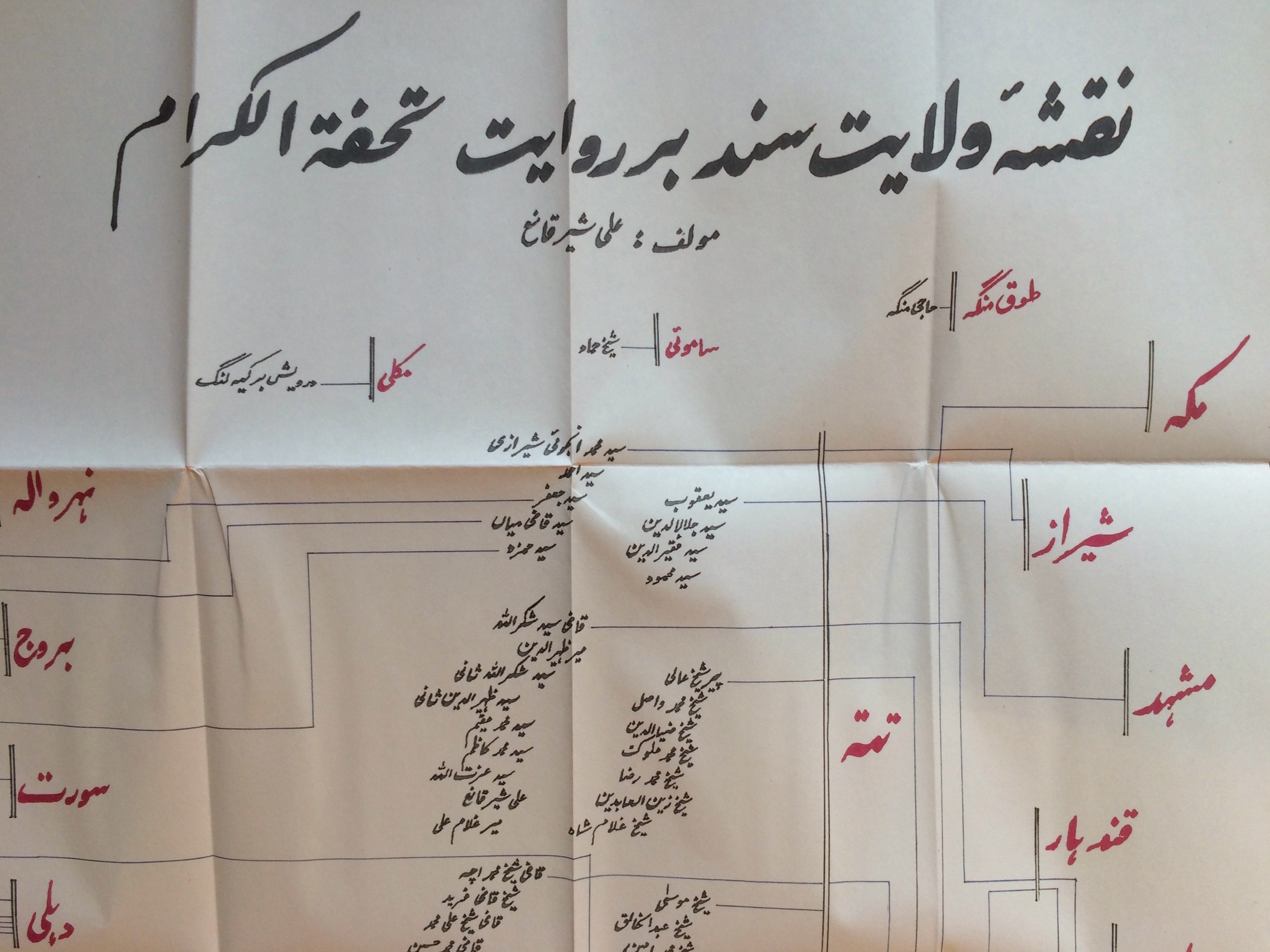

Shayan Rajani’s map fits perfectly in this sense, looking at the narrative geography of Sindh in the 18th century where geography was visualized in a very different way from how we see the world today. The 18th century map charts people based on their complex geographic lineages, and Karachi doesn’t even appear in it!

There is this idea of Pakistan in which Karachi is the most important city in all aspects, but in the 18th century it’s totally off the map and it wasn’t considered a city at all. So to acknowledge that absence in itself is interesting. But it also forces us to confront the fact that how we visualized nation and border was different in the 18th century.

By visualizing genealogies, Shayan’s map shows that people in Sindh were not a homogenous ethnic group, and to be a native of Sindh did not mean you had to be born there. What stands out in the map is this striking cosmopolitanism, mobility and diversity, where people came to Sindh from different parts of the world. This interconnectedness between different regions is something that’s become so alien to our understanding of the world today, marked by borders and political boundaries, where differences are no longer embraced but excluded on basis of citizenship and nationhood.

AjamMC: Even though Karachi is not on that earlier map, the city emerges much later as an exemplar of post-Partition Pakistan as a new kind of country. When you discuss the practices of seeing and cartography that have been erased, how do you see that in relation to Karachi’s modern history?

SR: The earliest maps you have of Karachi are colonial. It’s when the British conquer Karachi in 1839 that they start mapping Karachi and Sindh. Mapping as a strategy of power and conquest and control, in ways that are so familiar to us today in terms of how we represent the world through maps, only comes about as a result of colonial conquest. … It also raises the issue of that same kind of impulse and desire for surveillance and for complete transparency that is behind the whole discipline of mapping to begin with. That’s one of the limitations of mapping that we were very wary of in this project.

ZM: In many of the geographies written during the earlier centuries, a lot of the mapping was done through genealogy. It’s unsettling how these non-western traditions of visualization and spatial imagination have become so alien to us. In Islamicate cartography maps have a South-North orientation, but today that’s so foreign to us, we would see that map now as showing an upside down world. It’s a completely different way of seeing the world, which we are completely disconnected from today. We’re struggling to see what the tools would be to reconnect with those erasures.

AjamMC: That map was striking in terms of genealogies and the cosmopolitan histories themselves were embedded in the practice. The idea that people were by their very nature cosmopolitan and could trace their roots to many different places was central to the practice of mapping itself.

That contrasts so strongly with the logic of Partition, which was all about drawing lines and borders and mapping divisions between places and where people are supposed to be, in the broader sense as well as in the local sense of ethnicity or language-based politics in Pakistan. And in Karachi too, in terms of ethnicity or sectarian difference being a way to structure violence.

You get this direct contrast with the previous system of values that did see cosmopolitanism as natural and normative, and this is revealed by the mapping practices common at that time.

SR: Shayan’s map is situated in 18th century, but even in the early 19th century cosmopolitanism was a defining feature of Sindh. There existed incredibly diverse connections through trading networks that linked Karachi with the Persian Gulf, Central Asia, China and Africa.

But during the colonial period those connections get broken, and Karachi, which was previously so imbricated with these other regions through trading networks, is really isolated from the region.

AjamMC: Why do you think that today there is so much visualizing, thinking, and writing about Karachi as a city and a space?

SR: Maybe that’s not specific to Karachi, it’s common to all sort of expanding cities around the world. Even with Karachi, the constant visualization of this ever-expanding city, with its ever-increasing population, the boundaries of the city are imagined to be crawling outwards and pushing into barren land, where everything is being ‘developed’ and upgraded — there’s a fantasy of modernity in terms of thinking about Karachi as this city that is aspiring to world-class development and all of these different aspirations constantly being projected onto the city and its people, not just in the media, but also in other discursive spaces.

In the book, there’s a map made by myself and Anam Soomro that shows the history of the destruction and displacement of informal settlements from the city center to the peripheries, in order to ‘develop’ the city for elite interests . Even though it’s framed as examining the first two decades of Pakistan it’s still incredibly relevant for us today because these similar strategies of power and exclusion are still being applied.

Contemporary rhetoric around development comes with eerily familiar slogans and fantasies of progress and modernity and continues to rely on authoritarian strategies of exclusion in order to usurp land for the creation of elite, securitised spaces. These strategies are so pervasive, yet remain so hidden.