Originally published by Ajam Media Collective on March 2, 2016.

At the southwestern tip of India in the state of Kerala sits the elegant port city of Kochi, the bustling capital and tourism hub of a region famed for beaches, forests, and backwater lagoons. Kochi (previously Cochin) is organized around a Portuguese colonial fort town built atop what was once a trading port established by Arab traders in the 1300s.

At the southwestern tip of India in the state of Kerala sits the elegant port city of Kochi, the bustling capital and tourism hub of a region famed for beaches, forests, and backwater lagoons. Kochi (previously Cochin) is organized around a Portuguese colonial fort town built atop what was once a trading port established by Arab traders in the 1300s.

The museums and guidebooks in Kochi speak mostly of European “arrivals” and conquests and control, or else focus on the lives of royal families surviving detached from their surroundings with foreign support. But the streets tell a different, richer, and far more beautiful story than the official one. Around every corner, the curious visitor stumbles upon a synagogue, or a bright pink roadside Catholic shrine, or the proud, jagged Aramaic characters announcing a Syriac Christian house of worship.

Here there is a mosque, and beside it a Jain temple and further down a Hindu temple and a few ashrams scattered between them all. This little region of 30 million has long been a center of diversity, reflective of the centuries of Persian, Chinese, Dravidian, Arab, Jewish, East African, and eventually Portuguese, Dutch, and British cultures that Kerala has absorbed and transformed into its own.

The Indian Ocean was once crisscrossed by trade routes that connected the Western coast of India to the port cities of the Persian Gulf, the southern expanses of the Arabian Peninsula, and the Eastern coast of Africa, from the Horn all the way down to what is today Mozambique.

The Indian Ocean was once crisscrossed by trade routes that connected the Western coast of India to the port cities of the Persian Gulf, the southern expanses of the Arabian Peninsula, and the Eastern coast of Africa, from the Horn all the way down to what is today Mozambique.

In many of these regions, the rise of transoceanic empires — and the regimes of legal control over the oceans they initiated — and later the nation-state led to the decline of the coast and a reorientation toward inland regions of the country.

In areas where port cities retained their importance, economies were restructured locally and the movement of peoples and cultures that once characterized maritime trade declined precipitously. In a world of nation-states, where “national culture” was imagined as homogenous and the complexity of lived reality shut out in pursuit of the dream of some variant of the “one flag, one nation” model, coastal regions characterized by centuries of cultural and religious syncretism and exchange were awkward reminders of a past that had to be forgotten. Jewish Christians and Spanish Jews

Jewish Christians and Spanish Jews

The coasts of the Indian Ocean are today littered by such worlds, doggedly surviving and persevering despite all attempts at obliteration. Nowhere is this more so than in Kerala, where 30 million people live along a small stretch of coast under a staunchly socialist government and some of the highest standards of living in the country.

In addition to the region’s Hindu majority and large Muslim minority, there are around 5 million Christians in Kerala, or one-fifth of the population. The community traces its history back to 52 AD, when St. Thomas the Apostle is believed to have arrived in India and converted many Christianity. These churches preserved many of the features of early Christianity that were directly inherited from Judaism (like observing Saturday as the Sabbath) but were altered later in Christian history.

These communities were bolstered by influxes of Syriac Christians from Iran, and until the 1500s Kerala was a major center of the branch of Syriac Christianity known as Nestorianism that spread from Mesopotamia across Central and East Asia and managed to attract large numbers of Mongol and Chinese converts in particular.

In the 16th century, however, the Nestorian Church of the East split up amid infighting, with a large number of Christians switching to Chaldean (Catholic) churches. The rest remained within the Assyrian Church of the East. Except for those who converted to Latin Catholicism following the arrival of the Portuguese, Kerala Christians still use Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic, as a liturgical language, and they are closely related in religious practice (though not ethnicity) to the large communities of Syriacs and Assyrians that today live across northern Iraq as well as northeastern Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and southeastern Turkey.

While Syriacs and Chaldeans look to Iraq and Syria for inspiration, Catholics worship in Portuguese-style churches overlaid with tropical influences resembling the colonial churches of Brazil, Angola, and Mozambique.

But beside the introduction of Catholicism, the arrival of the Portuguese in the 1500s had grave consequences for Jews and Muslims. The colonizers enforced an Inquisition: Muslim Arab traders (some whom had been living in the region for generations) were expelled, Muslim Keralans were forced to flee inland, local Christian came under suspicion for engaging in practices resembling Judaism too closely and Jewish places of worship were destroyed.

The local Maharaja managed to put an end to the Portuguese policies of cultural destruction, saving hundreds of thousands of Jews and Muslims from a bloodbath similar to what occurred on the Iberian Peninsula.

While Kochi’s Christian communities are well-integrated into the broader population and scattered across the city, the situation of the city’s Jewish communities is very different. Of the estimated 8,000 Jews who trace their lineage back to Kochi, the vast majority today live in Israel, with only a few dozen left in India. And those who remain are fiercely divided along lines that have for centuries ensured the city’s competing Jewish communities rarely got along.

While Kochi’s Christian communities are well-integrated into the broader population and scattered across the city, the situation of the city’s Jewish communities is very different. Of the estimated 8,000 Jews who trace their lineage back to Kochi, the vast majority today live in Israel, with only a few dozen left in India. And those who remain are fiercely divided along lines that have for centuries ensured the city’s competing Jewish communities rarely got along.

Historically, three major Jewish communities lived in Kochi, each maintaining their distinction from the others as part of a close social hierarchy resembling the broader caste society Indian Jews are embedded in. The first are the so-called Black or Malabari Jews, who claim to be the descendants of Jews who left Palestine in the 4th century BC.

The first accounts of Jews in Kerala, however, come from the 800s AD, suggesting much more recent provenance. The community over time blended into Kerala’s majority-Malayalam culture and created a vernacular dialect called Judeo-Malayalam. The second group are the White or Paradesi (Foreign) Jews, who are Sephardic Jews that fled Iberia during the Catholic Reconquest in the 1300-1400s and the Inquisition of Jews and Muslims that followed.

The final group is composed of Iraqi Arab Jews who arrived under British rule, part of the famous Baghdadi Jewish trading diaspora that settled in towns and cities throughout British colonial possessions to profit from the Empire’s wide reach.

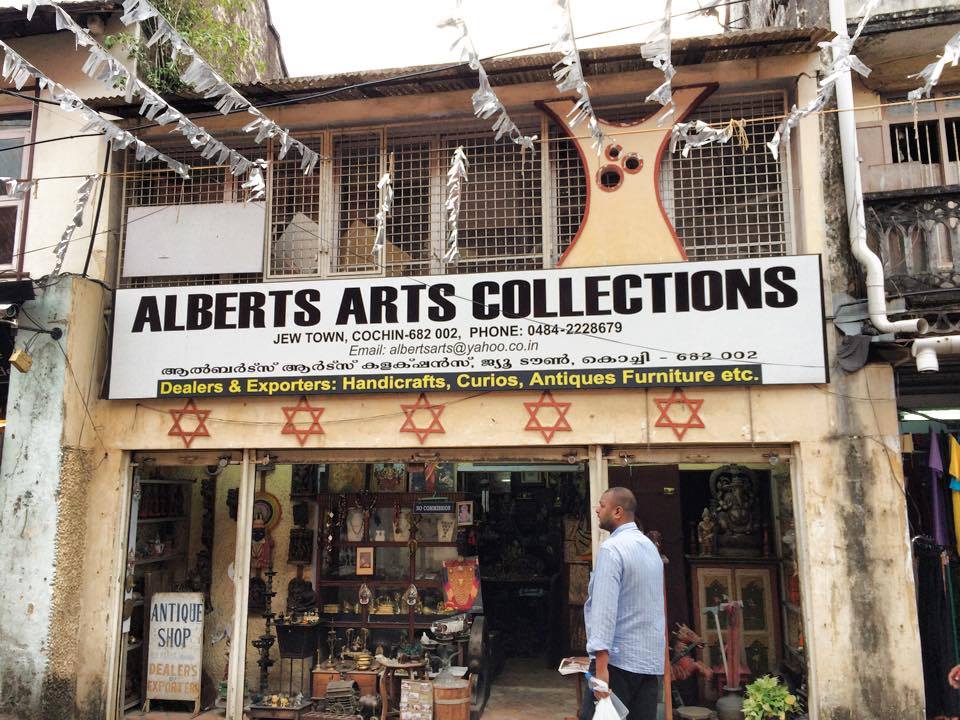

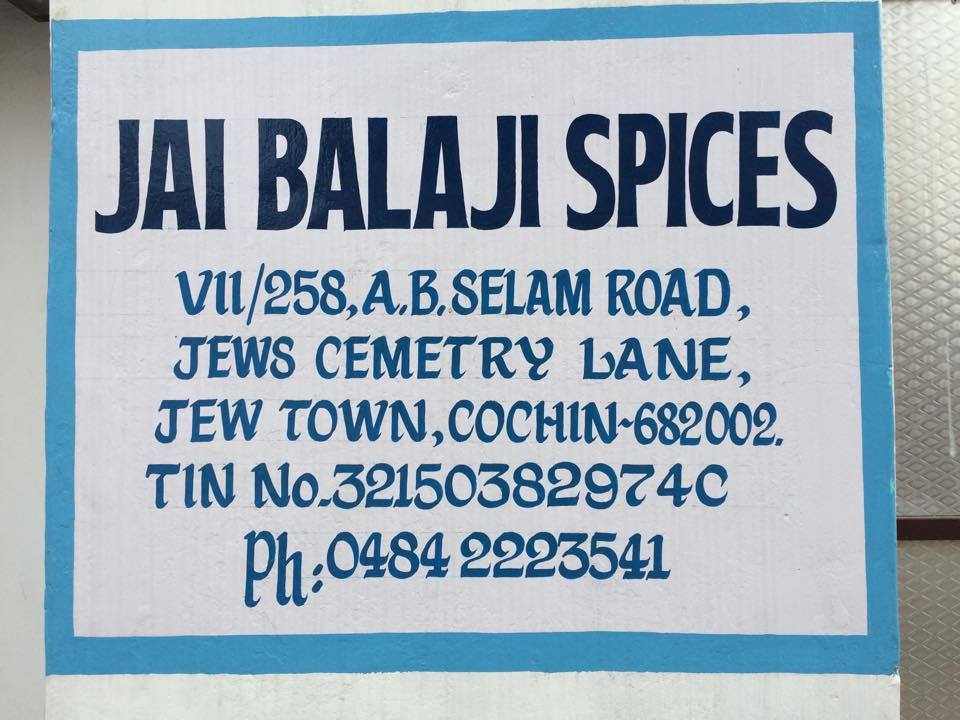

Of these three, only the Malabari and the Paradesi Jews maintained distinct neighborhoods. The Malabaris had a so-called Jew Town in Ernakulam, the contemporary city center, while the Paradesis had a Jew Town in Matancherry near the old city of Fort Kochi. Today, only the second remains.

Of these three, only the Malabari and the Paradesi Jews maintained distinct neighborhoods. The Malabaris had a so-called Jew Town in Ernakulam, the contemporary city center, while the Paradesis had a Jew Town in Matancherry near the old city of Fort Kochi. Today, only the second remains.

At the heart of the Matancherry Jew Town sits the Paradesi Synagogue, one of the extremely few functioning synagogues left in India. Established in 1568, the synagogue was built on land given to the Sephardic Jewish community by the Maharaja (whose palace is next door).

Although the Sephardic newcomers overtime stopped speaking Ladino and learned Judeo-Malayalam, they discriminated against the pre-existing Malabari Jews (hence the Black Jew-White Jew distinction) and did not allow them to become members of the synagogue. They had also brought freed slaves with them from Iberia, who similarly were denied membership.

Although the Sephardic newcomers overtime stopped speaking Ladino and learned Judeo-Malayalam, they discriminated against the pre-existing Malabari Jews (hence the Black Jew-White Jew distinction) and did not allow them to become members of the synagogue. They had also brought freed slaves with them from Iberia, who similarly were denied membership.

The community integrated into Indian society over many centuries and established itself as a high-level caste, adopting various aspects of Brahmin Hindu practice (especially regarding ritual purity of food, which is far stricter than most interpretations of kosher elsewhere). In the 19th century, the Jewish communities were joined by the Baghdadi Jews.

Jewish Kochi, however, was dealt a death blow with the triumph of Zionism in the Middle East. Since the establishment of Israel in 1948, the vast majority of Jews in Kerala have emigrated. Until the 1980s a few hundred remained and despite being small the community was still lively. But the out-migration continued to the point that today only a handful are left, mostly elderly. Kochi Jews in Israel, meanwhile, have largely assimilated into their new home.

A Museum of Jewish Diversity

A Museum of Jewish Diversity

As a result, despite the name, Kochi’s Jew Town neighborhood today has very few actual Jews. Beside the myriad Stars of David adorning the windows of many buildings, there is precious little pointing to the history of the alleyway in front of the Paradesi Synagogue. It is hard to believe that only 30 years ago, a street which has become full of tourist shops selling the same scarves and trinkets (and a few Menorahs) over and over was the beating heart of a vibrant community.

Jew Town has become a theme park, frequented primarily by large guided tour groups and cut off from the city it is a part of. The streets are clean, the decorations fresh, and the souvenir-hawkers ready. But one wonders how many pass through this place – a central site on any Kochi tourist itinerary – and snap photos, unsure of what they see but perhaps accustomed to understanding Jewish heritage worldwide as “museum objects.” I overheard one tourist ask if the Star of David, very prominent on the area’s little alleys, was there because “it’s the one on the flag.” The establishment of Israel not only massively reduced Jewish diversity through the destruction of so many communities, it also haunted and defined that which remained.

But these sites, of course, have afterlives. The tourist shops on Jew Town road are all run by young men, few of whom are from Kerala. When I asked one shopkeeper why no one on the road appeared to be from Kerala, he smiled and told me, “Tourists may know this place as Jew Town, but locals call it Kashmiri Town.”

Indeed, as I began speaking with merchants up and down the road (and happily shifting into broken Urdu whenever possible), I realized every single shopkeeper along the row was Kashmiri. The Indian military’s occupation of Kashmir had decimated the tourist trade there, but many of the region’s sons and daughters had managed to find work in other tourist sites across India.

Indeed, as I began speaking with merchants up and down the road (and happily shifting into broken Urdu whenever possible), I realized every single shopkeeper along the row was Kashmiri. The Indian military’s occupation of Kashmir had decimated the tourist trade there, but many of the region’s sons and daughters had managed to find work in other tourist sites across India.

While most of the former inhabitants had left for Israel and taken up homes on lands dispossessed of their Palestinian inhabitants in 1948, Kochi’s Jew Town had turned out be an unlikely refuge for entrepreneurial Kashmirs fleeing the military occupation of their own homeland.

On the other side of town in Ernakulam, far from the picturesque colonial old city and tourist crowds it draws in, is Kochi’s other Jew Town. Today, all but one of the Malabari Jews who once called this neighborhood home have left for Israel, and little remains to hint at the area’s former inhabitants.

But if you look closely and keep your eyes wide open, you’ll notice Hebrew inscriptions here and there. On the sign for a plant shop called “Cochin Blossoms,” a bumper sticker in Hebrew might catch your eye. And if you dare to enter the little alleyway to the store entrance, you’ll soon discover that you have reached the Kadavumbhagum Synagogue, these days tucked away behind a maze of tropical flowers, trees, and aquarium tanks filled to the brim with colorful fish.

Elias Josephai is the manager of both the plant shop and the synagogue behind it. Besides the occasional group of Israeli tourists, the synagogue sees few visitors these days (though businesses at the plant shop is steady).

Elias Josephai is the manager of both the plant shop and the synagogue behind it. Besides the occasional group of Israeli tourists, the synagogue sees few visitors these days (though businesses at the plant shop is steady).

But Josephai remains. He dislikes the few remaining elderly members of the Paradesi Jewish community across town, unsurprising perhaps given the centuries in which Paradesi Jews discriminated against Malabaris, and especially given the fact that they have managed to create a narrative of Jewish Kochi that positions their history and neighborhood as its center.

Josephai says that he has spent decades fending off entreaties from the Jewish Agency to move to Israel and instead devoted himself to collecting funds to repair the synagogue. But he complains that the stingiest of all have been the Kochi Jews living in Israel, who come back occasionally to look around but chide him for bothering to remain. From Israel, the idea of a diversity of Jewish life and the fact of centuries of Jewish existence among and a part of societies all over the world perhaps seems like a quaint relic of the past, not something to strive for in the present.

And perhaps they’re right. I witness Josephai offering a lecture to Israeli tourists in the synagogue and see their confusion at his diatribe against reducing the entirety of his existence to a little apartment on the 5th floor of a modern high-rise in the Tel Aviv suburbs. The tour guide hesitates repeatedly as she translates Josephai’s comments, and after passing around a collection plate and taking a few pictures, the gaggle of elderly Israelis in Bahama shirts and colorful shorts file out to continue their India vacation package.

And perhaps they’re right. I witness Josephai offering a lecture to Israeli tourists in the synagogue and see their confusion at his diatribe against reducing the entirety of his existence to a little apartment on the 5th floor of a modern high-rise in the Tel Aviv suburbs. The tour guide hesitates repeatedly as she translates Josephai’s comments, and after passing around a collection plate and taking a few pictures, the gaggle of elderly Israelis in Bahama shirts and colorful shorts file out to continue their India vacation package.

Despite his determination to preserve the synagogue, Josephai admits that one day soon, this will all be just a memory for him as well. His daughters in Israel are eager for him to retire and join them there. And as much as he wants to stay, he knows they’re right. It’s time to go. And with him, a piece of cosmopolitan Kochi’s soul will be lost forever.