Originally published by Ajam Media Collective.

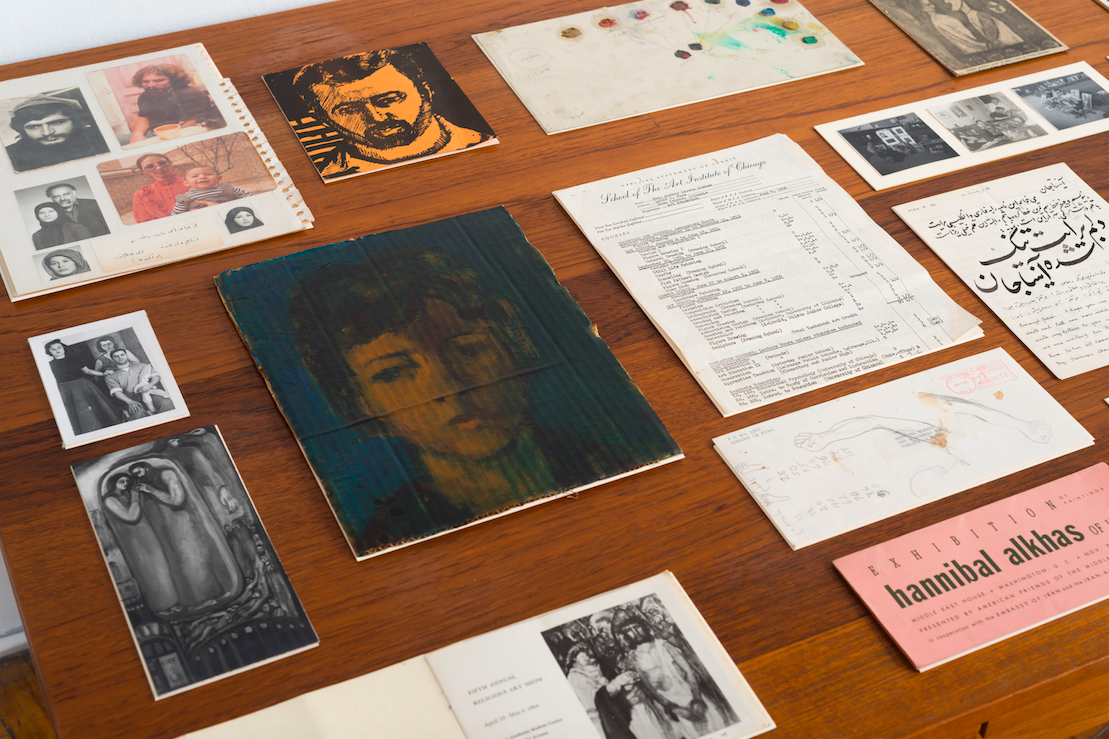

In 1951, a young Iranian man named Hannibal Alkhas moved from Tehran to Chicago, where he spent the next decade studying at the Art Institute of Chicago under the instruction of Russian painter Boris Anisfeld.

After his return to Iran, Alkhas went on to teach Fine Arts at the University of Tehran and established Iran’s first modern art gallery. True to his Assyrian lineage – his uncle Jean Elkhas is one of the most influential Assyrian poets of the 20th century – he named it Gilgamesh, after the ancient Mesopotamian epic hero.

Alkhas moved back and forth between the US and Tehran for the next half-century, building a life between the two that was informed by and influenced both. Alkhas maintained steadfast anti-imperialist political views throughout his life in both countries.

After the 1979 Revolution he became famous for painting the first murals on the US Embassy following the hostage crisis, when Islamist students stormed what they considered a “den of spies.” Among the murals were depictions of victims of the Shah’s secret police, key scenes of popular mobilization, as well as scenes from the takeover of the Embassy itself. These murals initiated a program of painting across Tehran headed by Alkhas that integrated elements of modernism, Soviet realism, and Latin American muralism that remain today highly influential in Iranian mural painting.

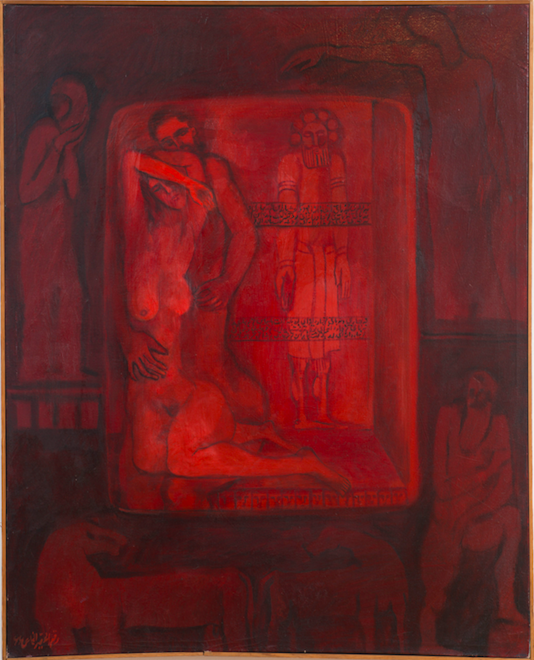

Alkhas is well-known in the Iranian art scene for daring experimentation in his work exploring emotion and the human condition. Less well-remembered, however, is the role the Art Institute of Chicago played in shaping his understanding of painting, sculpture, and modernism, and the continuing role this institution plays in Iranian and Iranian-American artistic production.

A new exhibit entitled Sedentary Fragmentation explores the history of the Iranian art scene in Chicago, bringing together the works of Hannibal Alkhas, Mehdi Hosseini, Raha Raissnia, Azadeh Gholizadeh, Yasamin Ghanbari, Nazafarin Lotfi, Elnaz Javani, Maryam Hoseini, and Sophie Loloie. The show runs July 14-August 26, 2017 at Heaven Gallery in Chicago’s Wicker Park neighborhood.

Curated by Kimia Maleki, a recent graduate of the School of the Art Institute from Iran, the show considers how migration and displacement shape artistic practices as well as how they create particular challenges for Iranian and Iranian-American artists. Maleki notes that the exhibition challenges the way generations of artists have been misrepresented by “having identities placed upon them that do not define them as artists.”

The title, Sedentary Fragmentation, “refers to the challenges of missing, seeking, and recovering an inner state or territory.” For Maleki, the term refers to an experience that many of the artists from Iran mentioned having sooner after their arrival in the US.

“Iranian artists are expected to represent Iran in their work, and thus to conform to certain expectations of what Iran looks like, especially things like veiled women and Persian carpets,” Maleki told Ajam, stressing that the success of Iranian artists like Shirin Neshat who focus on exotic images of Iran has been a disaster for Iranian artists who don’t want to be defined by their nationality.

“In museums here, curators still expect an Orientalist picture of Iran. They have an image in their head of Iran and that’s what they want to see when they meet an Iranian artist.”

As a result, Maleki notes, many of the artists stopped working soon after their arrival in the US – “they were silent and sedentary,” she adds – “but at same time their works were changing, and when they began producing work anew their practice was changed as well.”

Due to this pressure to “represent” Iran in their work, Maleki notes, many of the students who were born and raised in Iran have minimalistic and abstract styles. Second-generation artists, meanwhile, “are very excited by what is happening in Iran,” she continues, and as a result they are interested in engaging with Iran both as an idea and a reality in their works.

The show addresses three different groups of artists. The first is comprised of Alkhas and Mehdi Hosseini, an influential modernist who was part of the Midwestern art scene in the 1960s and is now faculty at the University of the Arts in Tehran. The 1979 Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War blocked Iranian travel to Chicago for decades.

But in the mid-2000s, as visas became easier for Iranians to acquire due to the end of the Bush administration, a second wave of Iranian artists made Chicago their home again, including Maleki herself. These artists coming from Iran over the last decade are the second group in the show. The third group in the show are Iranian-Americans, second-generation immigrants whose families mostly came around the 1979 Revolution and have grown up in the US.

In the exhibit, Maleki notes how the chronology of the Iranian art scene is deeply shaped by politics. The Pahlavi government’s patronage of foreign education for students (by 1976, 20,000 Iranians were studying abroad) and support for modernist art was instrumental in facilitating Iranians’ access to Chicago’s burgeoning cultural scene. The 1979 Revolution led to the cutting off of Iran’s relations with the rest of the world, a factor that amplified the influence of artists and teachers trained abroad before the Revolution, like Alkhas and Hosseini.

Today, as international sanctions and immigration bans continue to stalk Iranians as they travel abroad, Iranian artists’ connections with the Art Institute of Chicago maintain an outsized influence back home – just as their presence in Chicago enriches that city’s diverse cultural scene. Chicago is home to at least 40,000 Iranians, including a large number of Assyrians. Despite these figures, however, the city is often overlooked by other Iranian diaspora hubs like Los Angeles, Toronto, and Paris.

Maleki began working on the show three years ago when she began doing archival interviews with Iranian artists who had graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago, including Alkhas and Hosseini. She arrived in the US to study art management and curatorial practice, and plans to return to Iran to work in artistic archiving. She notes, however, that of the newer generation of Iranian artists trained in Chicago, the majority want to stay in the US.

One part of the problem is that under Trump, visas for Iranians are becoming highly restrictive yet again. Three artists – as well as Maleki – can no longer travel outside of the US, even to Iran, for fear that they will be prevented from returning because the new administration does not guarantee the validity of their visa past their initial entry to the country.

This forcible sedentarization of the artists in the show is not only physical, but is also reflected in the theme of Sedentary Fragmentation as explained by Maleki: “When an artist desires to move, to mobilize, and to create, it doesn’t happen instantly upon arrival. Disintegration of artistic practice tends to occur when there is a hesitation to understand the environment and to map out new territory. Creating a space can counterintuitively be acquired by remaining immobile, by re-creation through sedimentation.”

The show thus walks a tightrope between identifying all the artists involved as Iranian or Iranian-American while simultaneously flatly refusing to suggest that the artists are defined by their heritage. “Many have struggled against art criticism that uses their heritage as an interpretive lens for their practice, which raises the question: Why have art critics, curators and audiences persisted in identifying these artworks with a particular region?” Maleki notes.

In our interview she mentions how happy she was that when visitors entered the show, they were unable to recognize the nationality of the artists – instead evaluating the works independent of a perceived representation of Iran but instead on their own merits.

Maleki notes that Chicago connections have an outsized influence in Iran given the country’s isolation from international art centers, noting that they “act as lines communicating ideas about art that rise above the local, or what can be seen as provincial spheres … elevating platforms for art making both in Chicago and Tehran … and bearing witness to these lineages that are created by artists in their journeys from Iran to the United States and the threads that connect them to both places.”

Sedentary Fragmentation runs July 14-August 26, 2017 at Heaven Gallery in Chicago’s Wicker Park neighborhood. www.sedentaryfragmentation.com

All images from the show courtesy of Heaven Gallery.