Originally published on Ajam Media Collective on Feb. 16, 2021.

In markets across Iran, Tanakura Bazaars can be found dedicated to second-hand clothes, knock-off brand name shoes, and Iranian-made shirts at cut-rate prices. They attract a constant stream of bargain hunters looking for vintage clothes, which are referred to in Persian generally as Tanakura.

If you’re looking for a Persian (or Azeri or Kurdish…) etymology for Tanakura, you’ll come up empty handed. Despite its ubiquity in Iran, Tanakura is originally Japanese. But in Japan, the word is a relatively uncommon family name and the Persian meaning of second-hand clothes is nowhere to be found. So how and why did Tanakura become common in Iran?

The answer lies in a popular Japanese TV show broadcast on Iranian state TV in the 1980s. Oshin tells the story of a girl from rural Japan named Shin Tanokura whose life spans the Meiji period, Japan’s imperial expansion and military defeat during World War II, and the reconstruction and eventual prosperity that followed. The series offers an unflinching depiction of the tragedies and struggles of a working-class woman in Japan. Its harsh realism almost led to the show being passed up before it was broadcast by Japan Broadcasting Corporation in Japan in 1984.

At a time when the country was experiencing an economic boom after decades of recovery, the show offered Japanese audiences a chance to remember the long and difficult road they had endured. Oshin was originally shown in 15-minute episodes every day from 8:15-8:30 AM, targeting – and successfully attracting – a primarily female audience that also became the grounds for the show’s tremendous success in Japan.

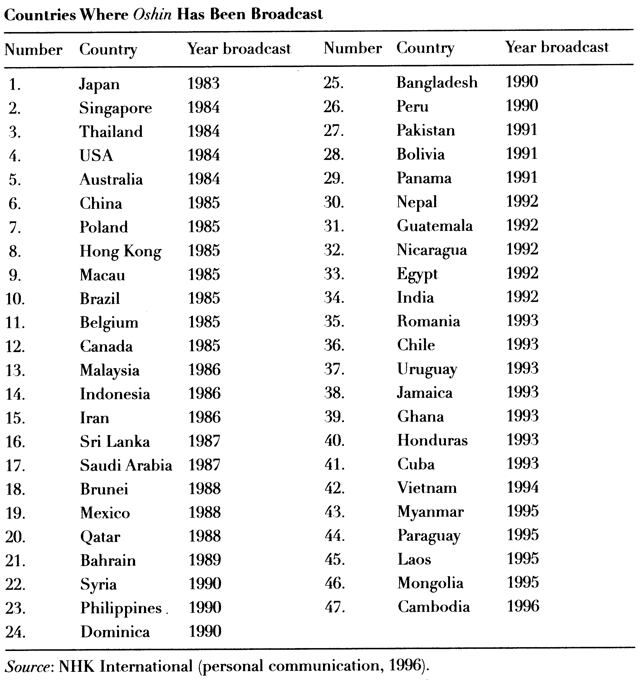

The show became a massive hit, and it is estimated that it was watched by at least 98% of Japanese TV viewers. It was soon being rebroadcast around the world – attracting fans in countries as diverse as India, Brazil, Egypt, Thailand, Iraq, Peru, and many more. The outbreak of “Oshindrome” worldwide even led to a 1991, international symposium in Japan entitled, “The World’s View of Japan Through Oshin.” To date, Oshin has been shown in at least 73 countries worldwide, in the process becoming a shared cultural memory that connects people around the globe.

In Iran, Oshin was aired every Saturday night at 9 pm. Its official title in Persian was Salhaye Dour az Khaneh, “Years away from home.” The streets emptied out as Iranians ran home to catch the latest episode, and it is estimated that the show attracted 89% of all Iranian TV viewers. At the time of Oshin’s airing, Iran was mired in a long war that began after Saddam Hussein’s invasion in 1980. Food rationing and bombing raids were the order of the day. Hundreds of thousands of men risked their lives at the front while women took up jobs to replace them back at home. The hopes and dreams fuelled by the 1979 Revolution, which had overthrown a US-backed dictator with surprising speed, became mired in the darkness of the years that followed.

Oshin was first broadcast in Iran in 1986. It was one of the first foreign programs shown on Iranian state TV after the Revolution at a time when few others were acceptable to the new religious standards. The show found a large and welcoming audience: despite hardship, television ownership had skyrocketed since the Revolution. Among the half of Iranians living in cities, TV ownership went from 22% in 1977 to 79% in 1986, and among rural households from 3% to 26%. By the time Oshin was broadcast in 1986, watching TV was a truly mass phenomenon involving the majority of Iranians, a stark contrast from a decade prior. The show quickly developed a devoted following who tuned in weekly to follow the twists and turns of Oshin’s difficult journey.

Oshin’s meteoric popularity in Iran reflects not only the show’s strong screenplay and complex characters but also its focus on Japan’s complicated history. The country’s rise in the 19th century to rival Western hegemony made it an object of fascination for Iranians, along with many across Asia who saw the country as a model of independent Eastern modernization. In order to understand how Tanakura came to be associated with vintage clothes in Iran, we need to dig back a little earlier to trace the history of Iran’s ties with Japan.

Iran and Japan have been tied through trade since at least the 1500s. Formal relations date to 1870, when Nassereddin Shah met Japanese diplomats while on a trip to St. Petersburg. At the time, both Meiji Japan and Qajar Iran had embarked on efforts to modernize their countries. Japan’s constitutional model and victory over Russia in the 1904-5 war would come to inspire many across Asia as the first non-European state to achieve modern economic, diplomatic, and military strength. This contributed to a wave of Asian revolutions demanding parliamentary government, including in Iran (1906), the Ottoman Empire (1908), and China (1911). In the decades that followed, Japan increasingly reached out to the Middle East as part of ambitions to build a pan-Asian empire, and by the 1930s, Japan was one of Iran’s main trading partners. These ambitions were foiled after Japan’s defeat in World War II.

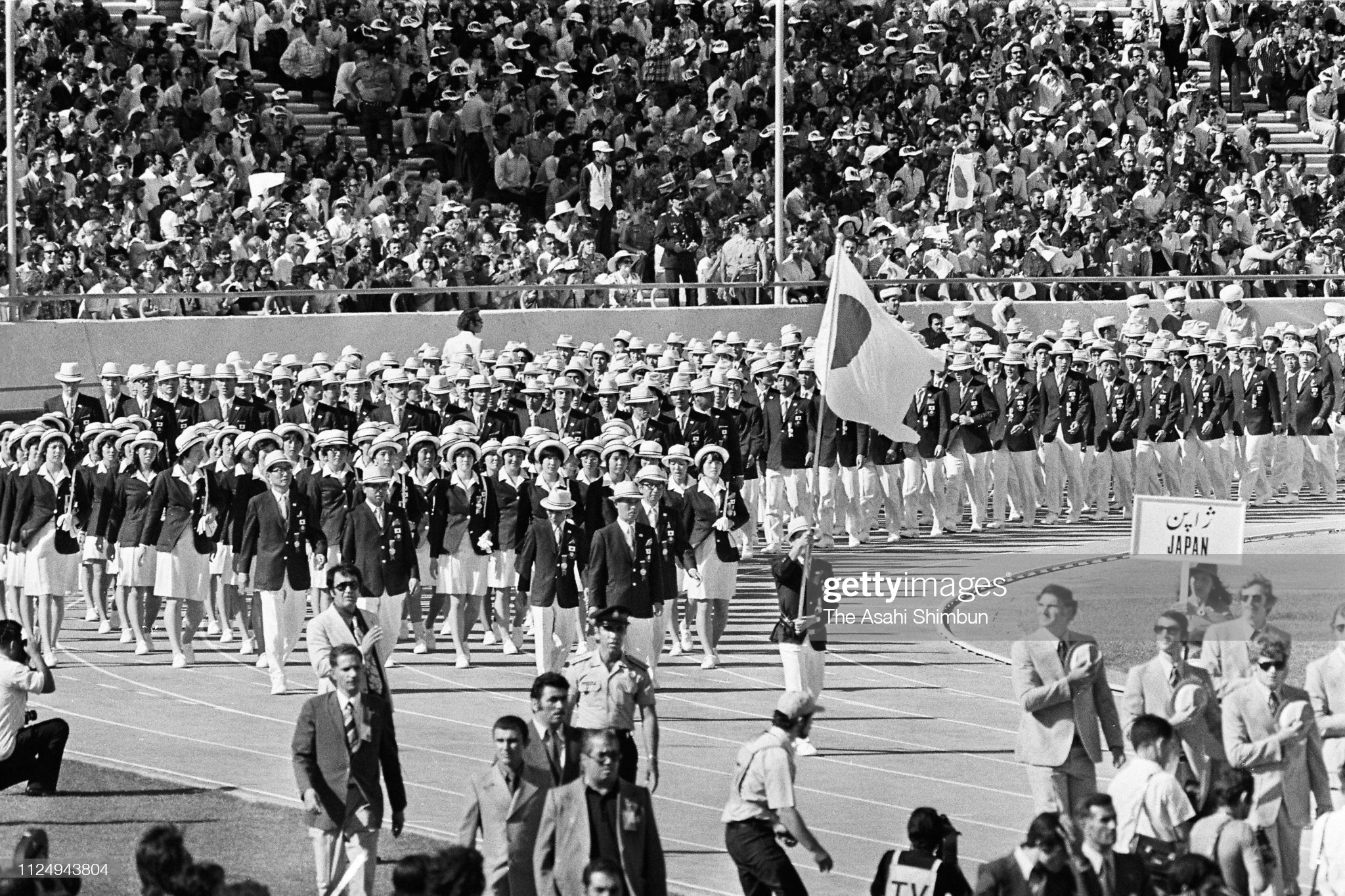

In the decades that followed, Japan rebuilt its economy to become one of the world’s most prosperous. Iran’s king Mohammad Reza Pahlavi increasingly saw its industrialization as a model for Iran, which he hoped would become the “Japan of West Asia.” These ambitions reached a pinnacle with the hosting of the Pan-Asian Games in Tehran in 1974, which were closely linked to Iran’s aspirations to become a superpower in the Indian Ocean, modeled on Japan’s strength in the Pacific. Hundreds of millions of dollars were spent to host the games, including the construction of Azadi Stadium. Japan came first in the medal count, with Iran second.

Japan continued to inspire Iran as a model even after the 1979 Revolution. Japan represented an indigenous Asian superpower challenging Western economic hegemony without sacrificing its ancient cultural roots. Policies modeled on the East Asian export-oriented capitalist economic model were adopted to help speed Iran’s transition in Hashemi to an “Islamic Japan,” as described by former President Rafsanjani. This included expanding car and electronics production and the creation of centrally-controlled free trade zones, which opened up direct trade connections.

One of the first Japanese goods to take the Iranian market by storm was the black fabric used in chadors, long black veils worn by many religious women in Iran. Japanese fabric became famous for its high quality and durability. Many chador makers chose the names of well-known automobile manufacturers for their product; as a result, many Iranian women today cover themselves in Mitsubishi or Lexus brand veils.

The rise of Japan’s economy in the 1980s was accompanied by growing interest in Japanese pop culture. Although in the years following the Revolution, Iran’s state TV refused to air Western television or movies, beginning with Oshin in 1986 it became increasingly open to foreign media, starting first with Japanese and later South Korean soap operas, expanding to Indian movies, and eventually adding vintage European and American movies as well.

Oshin’s influence reached every corner of Iranian society. The show even played a key role in changing standards of beauty at the time. In contrast to a beauty benchmark that stressed light hair and eye colors, the show popularized Oshin’s looks among Iranians. Oshin’s round face and almond-shaped eyes diversified benchmarks of Iranian beauty, with many babies coming of age at the time compared to her and girls who modeled their hairstyles on Oshin’s being called Oshini – “like Oshin.”

After Oshin, many other Japanese shows would come to find widespread popularity in Iran, such as Captain Tsubasa (i.e. Captain Majid) in the 1990s. But Oshin holds a special place in Iranian collective memory. This is due not only to its status as the first foreign show broadcast on TV after the revolution, but also the powerful story of resilience that it portrays. And it is from this story that the second-hand clothing markets of Iran acquired their name, Tanakura.

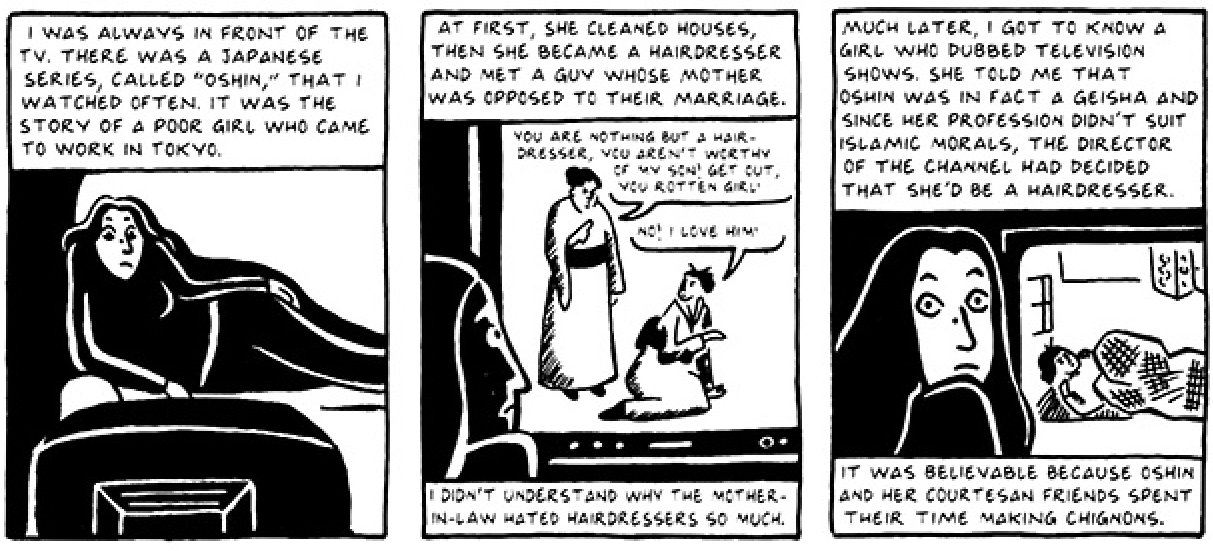

In the series, Oshin is forced to take a number of hard jobs to make ends meet, suffering great mistreatment along the way. This included working as a hairdresser, which is depicted as being an extremely lowly and even dishonorable profession for Oshin. Interestingly, this depiction led in Iran to persistent rumors that Oshin was in fact involved in sex work, but that Iranian censors had dubbed these details out. In fact, these rumors appear to be completely false; in the original Japanese show, Oshin was indeed a hairdresser and never got involved in sex work (although another character on the show did, which may have been the source of the rumors). The rumors are today widely repeated as fact – even in newspapers. An Iranian actress even shared an anecdote about visiting Japan and excitedly asking about the details of Oshin’s life that censors had hidden from Iranian viewers, only to be met by laughter.

The show depicts Oshin eventually moving to Tokyo and opening up her own stall selling clothing in a night market. With the income from her own clothing stall, she is finally able to make a good living and find a better life, slowly but surely.

Oshin’s success at opening her own clothing stall is what inspired the meaning of “Tanakura” in Iran today. Beginning in the 1980s in Mahabad, in Iranian Kurdistan, a market opened that specialized in clothing smuggled by kulbars over the border by the crate load. These clothes had often been sold several times over by the time they reached Mahabad’s bazaar; it was not uncommon to find brands like Nike or Adidas but also the jerseys of American high school basketball teams or 1980 Los Angeles Olympics-branded gear. Inspired by Oshin’s success with her clothing stall – and Japan’s success rebuilding its economy – the merchants of Mahabad’s second-hand clothing markets named themselves Tanakura Bazaar.

Soon, Tanakura Bazaars could be found in many cities across Iran, starting with cities close by like Urmia, Khoy, and Sanandaj, but soon spreading to Qazvin, Mashhad, and elsewhere. In Tehran, Gomrok Square is famous as a hub for Tanakura. Tanakura has become the common word for second-hand clothes across the country – both imported vintage and domestic second-hand – and in almost every city across Iran, Tanakura shops and bazaars can now be found.

The trials faced by Oshin and her eventual success made her beloved by Iranian women in particular. The hardships of wartime pushed many Iranian women to seek alternative sources of income outside of the home, often involving informal jobs like street vending or resale. As a result, Oshin became a role model for many women. In 1989, a small controversy erupted after a call-in interview with ordinary Iranian women asking them to name the best role model for Iranian women. Most interviewees offered religious figures as an answer. But one woman responded to the question by arguing that Oshin was the best role model for Iranian women. This may not have been the answer TV authorities expected, but it highlighted just how much Oshin’s independent-minded attitude and perseverance in the face of adversity had inspired Iranian audiences.

To this day, Oshin is fondly-remembered in Iran. For the generation that came of age during the Iran-Iraq War, her story is indelibly linked to the hardships of wartime experienced at the time of airing. Continued rebroadcasting of the show on Iranian TV has kept the memory alive for younger generations. The show’s worldwide popularity, meanwhile, has woven it into an indelible part of global collective pop culture memory. And even though Iranians may not be aware of it when they shop at Tanakura Bazaars, they take part in keeping these shared memories alive every time they use Oshin’s family name to refer to Iranian vintage clothes.

References

Chegini, Mohamed. “Ravabit-i Bazargani Iran va Japon az Aghaz ta Pahlavi Aval.” Tarikh Ravabit-e Khareji, no. 70 (spring 1396), 131-168.

Chehabi, Houchang. “The Juggernaut of Globalization: Sport and Modernization in Iran,” The International Journal of the History of Sport, vol. 19, no. 2-3 (2002), 275-294.

Haag-Higuchi, Roxane. “A Topos and Its Dissolution: Japan in Some 20th Century Iranian Texts,” Iranian Studies, vol. 19 (1996), 71–84.

Huebner, Stefan. Pan-Asian Sports and the Emergence of Modern Asia: 1913-1974. NUS Press, 2016.

Koyagi, Mikiya. “The Hajj by Japanese Muslims in the Interwar Period: Japan’s Pan-Asianism and Economic Interests in the Islamic World,” The Journal of World History vol. 24, no. 4 (2013): 849-876.

Koyagi, Mikiya. “‘As Fellow Asians?’ Irano-Japanese Relations in the Interwar Period,” in Mehdi Khorrami and Behrad Aghaei eds., A Persian Mosaic: Essays on Persian Language, Literature and Film in Honor of M. R. Ghanoonparvar (Ibex Publishers, 2015), 70-85.

Kuroda, Kenji. “Pioneering Iranian Studies in Meiji Japan: Between Modern Academia and International Strategy.” Iranian Studies, vol. 50, no. 5 (2017), 651-670.

Pistor-Hatam, Anja. “Progress and Civilization in Nineteenth-Century Japan: The Far Eastern State as a Model for Modernization,” Iranian Studies, vol 29, no. 1-2, 111-126 (1996), 111–126.

Rajabzadeh, Hashem. “Japan as Seen by Qajar Travelers” in Daniel, Elton L. (ed), Society and government in Qajar Iran: studies in honor of Hafez Farmayan (Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers, 2002), 285-309.

Singhal, Arvind & Udornpim, Kant. “Cultural Shareability, Archetypes, and Television Soaps: ‘Oshindrome’ in Thailand.” Gazette, vol. 59, no. 3 (1997), 171-188.

Sugita, Hideaki. “The first contact between Japanese and Iranians as Seen through travel diaries” in Worringer, Renee (ed), The Islamic Middle East and Japan: Perceptions, Aspirations, and the Birth of Intra-Asian Modernity (Princeton: Markus Wiener Publications, 2007), 11-31.