Originally published in New York Magazine on Oct. 13, 2022. Written by Alex Shams.

Since mid-September, Iranians have taken to the streets to protest the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini (who primarily went by her Kurdish name, Zhina). After morality police stopped her for being “improperly” dressed, Amini was taken into police custody — only to emerge days later in a body bag. Thousands across the country reacted with fury and mourning, uniting under the banner of “Woman, Life, Freedom,” a Kurdish freedom slogan repurposed to demand women’s rights in Iran and an end to dictatorship under the current regime. Triggered by the violent enforcement of a government dress code that includes mandatory headscarves for women, the initial outcry has morphed into the largest protest movement Iran has seen in years.

Beginning in Saqqez, the town that Amini was from, protests spread to major cities like the capital, Tehran, and Mashhad and to ethnically diverse regions including Azerbaijani Turks, Arabs, Baluchis, and others. Despite a government crackdown by both police and a plainclothes paramilitary group called the Basij that has left more than 200 dead and many more in prison, the movement is now in its fourth week, and it can be found in high schools and on college campuses, at oil refineries, and in city streets across the country. Defiant young women have become visible as leaders and symbols of the protests — with the deaths of more girls and women like Hadis Najafiand Nika Shakarami at the hands of security forces further galvanizing public anger.

We spoke to people in Iran who have risked their lives at protests from Saqqez to Mashhad (a religious center and Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi’s birthplace), Tehran to Sistan and Baluchistan, a region that witnessed a massacre in late September by security forces. Out of concern for their safety, they spoke on condition of anonymity, and our conversations took place over voice notes and chats set to expire. They spoke about what it’s been like on the streets over the past month and what has kept them going. “Every time I leave my home, I hide my keys, I give my laptop to someone else, and I tell friends and family that I’m going out,” a teacher in Tehran said. “We all know anything could happen to us when we step out onto the street.”

Male Journalist and Political Activist in Saqqez, 35

Since the day we found out Zhina had been hurt, the mood in Saqqez has been dark and full of fear. Her family was well known around town. From the beginning, everyone was waiting to hear how she was doing. Authorities wouldn’t give any details to the family about what had happened, and they put intense pressure on them to bury her quickly. But Zhina’s family stood firm, and the case was publicized. Large crowds came for the funeral. People wanted to stand up and support her family.

When her body reached the cemetery, crowds began yelling slogans in Kurdish: “A martyr does not die!” People were very upset. The crowds kept yelling, “Don’t be afraid!” meaning they were there to support the family. The crowds went to the police station and continued yelling slogans. The day after the funeral, shops across the city went on strike and refused to open. There was a call by Kurdish political groups for people to take part, and they did. Protests began almost immediately; so did the arrests. Many prominent people in town have been detained. But the protests continue. The bravery women have shown is really incredible. At one protest, a 15-year-old girl was hit by a rubber bullet. People took her into an alley to try to give her medical care, but she refused and said she would stay in the street fighting.

Starting on Saturday, October 1, things became very difficult. The Revolutionary Guards came into town with heavy weapons and took over many major squares. They stand there around the clock, dressed for war, and shoot directly at people who try to gather. The city went on strike in response. Teachers refused to teach their classes, and students refused to go to school. The students at boys’ schools went on strike in solidarity with the girls’ schools.

The evening after the strike, there were protests and clashes with security officials. Every day, people are waiting for a spark for something to go off. It can be someone honking loudly or a group of young people who go into the street and suddenly start shouting slogans. Out of nowhere, they arrive, protest, then disperse. During the day, word spreads that in the evening, people should take to the streets, and they do.

Female Software Engineer in Tehran, 29

The anger I felt after I saw what happened to Mahsa Amini was unlike anything I’d ever felt. The first day afterward, I heard about a protest on Keshavarz Boulevard. From the morning, all I could think about was getting there. Nothing else mattered.

When I arrived, there were huge crowds of people that kept getting bigger and bigger — as if people were coming from every single direction. The riot police were just arriving. The crowds were way bigger than the security forces. The cops didn’t approach us at first. Trucks with water cannons started spraying at us, but people refused to leave. No one moved. I saw an older woman walking in the middle of the street. She went right in front of the water cannon. It kept shooting at her, but she didn’t budge. All of a sudden, as people watched her, they discovered their own bravery. Everyone started rushing toward the riot police. They started picking up stones and whatever they could find and throwing them at the cops, who began to retreat. By the time they sped away, all the cop cars’ windows had been crushed to bits.

Suddenly, the street was in the hands of the people. Plainclothes police on motorcycles started arriving, but since huge crowds were occupying the streets, they couldn’t get through. Everyone nearby started taking part however they could: Store owners closed their shops and joined us, people started directing traffic; others started passing out water. That day, whenever the police shot tear gas at us, people would help each other however they could — like by lighting cigarettes close to each other’s eyes to wash out the gas. Strangers would band together in groups. Friends of mine who were political activists were taken from their homes by the police. We still haven’t heard anything from them.

On the second day of protests, they closed the streets off much earlier. The security forces were firing tear gas all over town; even the small alleys were full of it. The police became more violent — they drove around on motorcycles with their weapons out. A few of my friends got beaten up. Plainclothes cops would appear and suddenly snatch people’s phones so they could try to identify them later. By the third day, there were so many police officers on the streets in the city center waiting for people to protest that it was impossible to gather. I saw people like me everywhere waiting for a chance to start. But the police were everywhere. And the second they saw someone pause or take out their phone, they would jump on them and take them away. You couldn’t even stop for two seconds. A lot of people tried to reach the city center, but the cops had closed off the streets. That was when people started holding protests in different parts of the city instead of just the center. As the protests became constant and continuous, the police became much more aggressive. They would just pick people up off the street and keep them for the night.

I’m preparing for more protests. From the first day, I put my scarf in my bag and never put it back on my head. We know that we can be arrested for not wearing our scarves, but we know that people will defend us. And the police know how angry people are. At night, I look online for tips on how to defend myself: if they tie my hands and legs, how I should fight back. We share this information with each other and take it very seriously. Because we know that, at any time, we could be arrested or killed.

I don’t think these protests will ever stop. They will keep going, and more people will put their fear aside and join them. I am certain that more people will take up resistance against the government. The government has tried for years to turn men and women, Turks and Kurds, Arabs and Persians against each other. But they haven’t been successful. If you asked me last year about the future, I would have been hopeless. But if you ask me now, I would say I was wrong.

Female Civil-Society Activist in Tehran, 44

At first, protests were mostly during the day in central Tehran. Now they take place at night — except for student protests that happen during the day. I usually leave my house to meet friends to protest around 5 p.m. and am out until 8 or 9 p.m. every night. We march, we chant, we get beaten by the police, and we do it all again. I haven’t lost any friends, but many of my close friends are currently in prison. Every day that we leave the house, we have a hope that did not exist before the last few weeks.

When I wake up, I first check the internet with a VPN to see what has happened since I fell asleep. After this, I talk to friends in Iran and outside Iran and try to do a few hours of work. We check up on people who have been arrested and sent to jail. We call their families. We strategize where we’re going next. This is ever-present in our minds all day. When we go outside, we try to go without a scarf.

It’s definitely not just about hijab — it is a general unhappiness with the status quo. I do want the option to choose. If given the right to choose, I haven’t decided yet if I’d want to wear it and how I’d wear it. What is a priority for me is true freedom, collective freedom — where we have a route to express our grievances. It’s striking for me to see the younger generation on the streets — people in their early 20s. They are extremely brave — more so than I. I think the government itself was not expecting this generation to be this fiery. Any stereotypes about women as fragile and weak are completely gone.

In most of the streets in the city center, people chant from their homes, blast music, and find each other. This is one way we create resistance. But the number of police is double the number of people in each neighborhood. I have never seen crowds start violence; it’s always the police. They have no idea what to do with the crowds. In Tehran, we haven’t experienced killings yet like in other places, because the cops are afraid of people filming and recording what they do.

It’s clear that there is a lot of conflict within the police too. On multiple occasions, I’ve seen them get in arguments among themselves. If they see a group of mostly women or young kids protesting, there will be some officers who block the others from reaching them. We try to convince them to join us in solidarity. But there are plainclothes police, mostly on motorcycles, who are harder to identify. They are much more violent.

There is a lot of disagreement within the government itself. They are really worried that Iran will become like Syria. We think that if we don’t protest, worse times will come, so it’s important that we fight for our rights now. My friends and I gather each night and discuss what’s happening, and we recognize that we’re not alone — there are so many of us. It is a leaderless movement. Everyone here is sick of those who call themselves leaders: the MEK, the Shah’s supporters, activists like Masih Alinejad, the reformists, celebrities — we just want ourselves. This means that we work to get more people to join us on the streets, because it is for us, by us. A government we will all work together to create. People have no trust in anything that has the slightest relationship with the state. And they have very, very little trust in anyone connected with foreign organizations or countries.

I have a lot of hope from what I’ve seen on the street. People are more united than we’ve ever seen: in big and small cities, religious and less religious cities. But I’m afraid there could be more violence in the country and that foreign countries could interfere and create conflict. There is a collective pain in the country that is ours and ours alone. It is not influenced from the outside. Only we can achieve justice for ourselves.

Male Civil-Society Activist in Sistan and Baluchistan Province, 32

The situation in Sistan is very militarized. The police are everywhere. For a few days, people here came out into the streets. But a number of people were killed, and security forces are now everywhere. Still, the protests continue.

The main issue here in Baluchistan is the case of a girl who was raped by a police commander. People came out to protests because of what happened to her and to Mahsa Amini. They want justice. Many women came into the streets to protest. But the repression has been very strong. Riot police and Basijis are everywhere. One of my friends was killed. I’m very, very afraid.

Male Student in Mashhad, 27

The first protests I saw were at Ferdowsi University. I was nearby and heard shots in the distance. Students protesting inside were surrounded by police, who were trying to disperse them by shooting in the air. Fear spread throughout my entire body. I shook uncontrollably. That night, sleep was impossible.

The first public protest in Mashhad was a few days later. It was almost all young people and teenagers wearing dark clothes. At first, the police did not react. Around them, plainclothes police were filming. Soon after, a middle-aged man with a walkie-talkie came running and said, “We have received the order to break it up!” The police forces immediately started to disperse the people by firing tear gas. Cops on motorcycles arrived and blocked off the street, pushing protesters into the alleys. A feeling of terror overcame us. As the sun set, we were surrounded by the sound of gunshots, the smell of tear gas, and the fear of people passing by.

For several days after, the sounds of protest could be heard scattered all over the city. But they would always be suppressed in the first few minutes. The whole city was full of security forces. Cops blocked off the main avenues, where they thought protests could occur, and turned the lights off to plunge the streets into darkness. Alongside the uniformed police stood many more plainclothes Basiji units. Some of them were clearly minors. For a few days, police were all around town and the internet kept getting shut off. Slowly, things came back to normal. But seeing what was happening in other cities, the anger of people in Mashhad flared up again. Scattered protests erupted around town. Late into the night, cars would drive around honking in protest.

The key point for the movement in Mashhad was Saturday, October 1, the first day back from summer break for schools and universities. Protests broke out on the campuses. Some girls blocked the streets and chanted, “Death to the Dictator” and “Death to the Oppressor,” whether it be a shah [king] or rahbar [religious leader] while waving their scarves in the air. Police shot protesters with paintball guns to identify them.

The protests at universities continued all week. They were decentralized and had no clear leader. Every few minutes, a slogan was raised from a corner of the crowd, and within seconds, it was shouted by everyone else. It was as if a collective mind was leading the group. When people became thirsty, students ran to the cafeteria to bring water to pass out.

It’s not unusual to see girls wearing hijab among the protesting students. Girls with scarves and girls without scarves hold hands together and chant slogans demanding justice and freedom of choice to wear what they want. It is common to see women without scarves walking around the city. I saw a young girl without a scarf boldly pass in front of police on the street. A few meters away, some young Basijis ran after her. The girl continued walking slowly. When the Basijis approached her, she turned around and shouted, “What, what? Come on, kill me. Don’t you want that? Just like you did to Mahsa and Hadis?” All three of them stopped dead in their tracks, shock visible on their faces. They didn’t dare say another word.

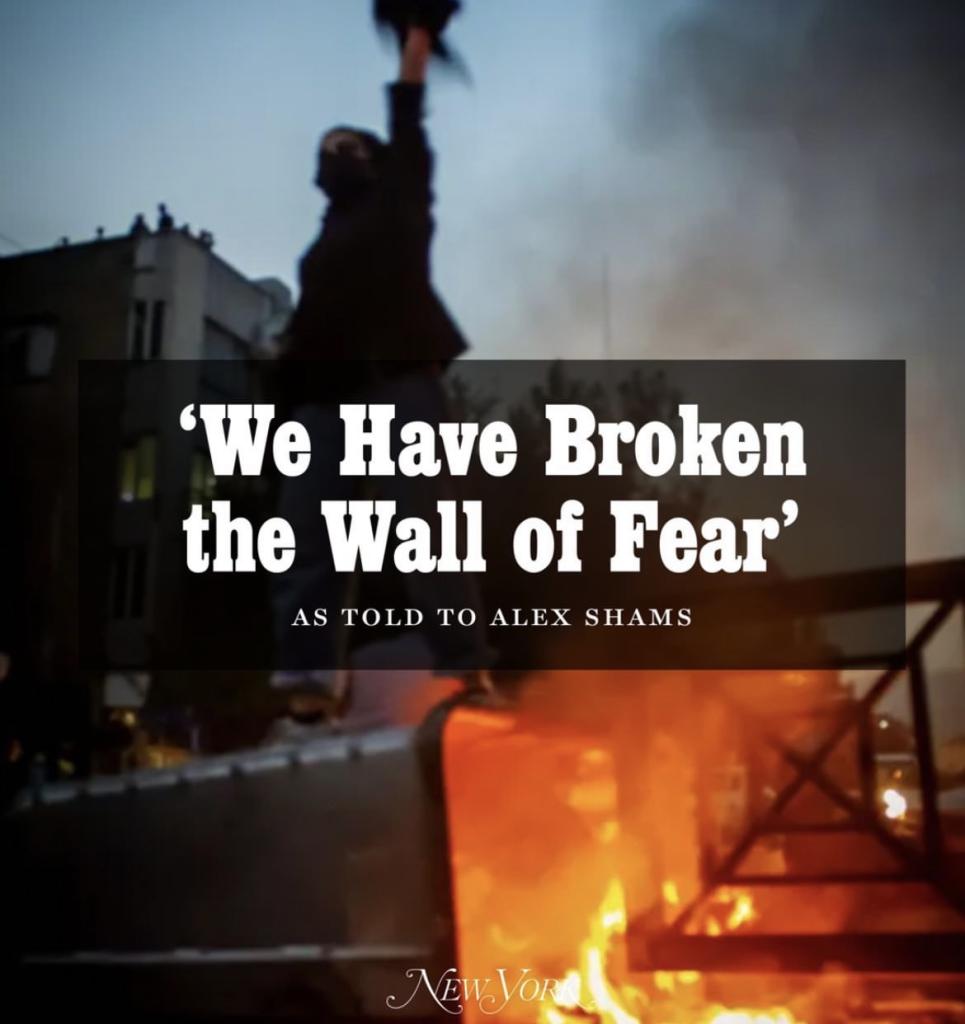

Even if the government wants to fight to enforce the dress code, it can’t. It’s impossible to count how many women are bravely walking without their headscarves. These days, no morality police can be seen on the streets. We have entered a path of no return. Protesters have organized, and previously marginalized people have found each other. We have broken the wall of fear. The government will have to retreat. People have called for the government to reform, and it didn’t listen. Now the government feels threatened, and in turn, the people refuse to listen.

Female Teacher in Tehran, 30s

The mood these days is fearful. Every time I leave my home, I hide my keys, I give my laptop to someone else, and I tell friends and family that I’m going out. Because of the intensity of violence and arrests, it’s better to prepare yourself beforehand for all possibilities. We all know anything could happen to us when we step out onto the street.

These protests are building on the momentum of the movements that came before us. Mahsa Amini’s lawyers are fighting for justice in the courts. The demand that the law should protect all people equally is a return to the demands of the Constitutional Revolution. The slogans on the street for equality between classes is a return to the 1979 revolution’s demands. Our way of thinking about activism and women’s rights is indebted to the One Million Signatures campaign, student movements, Reformist struggles, and the 2009 Green Movement. Even though these movements didn’t succeed, the experience has become part of this movement. This includes other movements like Black Lives Matter, which inspire us about how to understand our struggle. The heritage of Me Too is in this; you can see it in the protest slogans we say: “Man ham Mahsa, Man ham Nika” (“I am also Mahsa, I am also Nika”). And as the protests in Baluchistan over the rape of a minor show, these protests are fighting for the idea that you don’t need to be a celebrity for your voice to be listened to. We are finding each other at the intersections of our oppressions. This is not intersectionality in theory but one in practice that we feel with our skin and bones.

It’s very important that all those people outside Iran watching us right now understand something about our slogan, “Woman, Life, Freedom.” They need to understand this slogan’s relationship to themselves. This is a critique of unequal power relations in all forms — of anyone who is stepping on your rights and limiting your freedom. This critique can be applied in every time and place. The worst thing that could happen would be if people in other countries look at us and see us as poor, oppressed women who are stuck fighting for rights like American and European women did a century ago — that they think we’re at the beginning of the road. People need to understand that our fight is shared with people all over the world including themselves.

When we protest, we don’t go as part of separate groups or political parties; we join together as one. We’re constantly moving around, making a protest happen wherever we happen to be. If you’re in traffic, you honk; if you’re in the streets, you yell slogans; you occupy whatever space you can, moving around until they come on motorcycles and fire tear gas. You yell slogans, even if just for a few moments, then disappear again.

When they arrest someone, we all feel like we could be arrested. But that’s exactly what makes us brave. If everyone is a criminal, the punishment can’t be that crazy. If everyone is resisting, how many forces can they possibly have that they can beat and kill us all? People in the depths of their souls are afraid. They’re ready and aware that at any moment, anything could happen.